If boomers are smugly gif-ing all over Facebook from a house they bought for £3.50, millennials are obsessed with avocado toast and whining, and Gen Z are shunning IPA in favour of climate activism, then Gen X are – so the stereotypes go – louchely far too cool for any of that stuff.

Variously characterised as the generation of latchkey kids, slackers, and MTV, Gen X sits in an interesting space when it comes to how they’re being marketed to and what they’re being marketed – interesting in that, for the most part, it seems brands and advertisers are ignoring them.

But why? If Gen X were born between 1965 and 1980, they’ll be roughly 43–58 years-old now. In other words, a generation that likely has more disposable income than those younger, and one with a rich cultural history (Trainspotting, grunge, readily available Clockwork Orange posters, Blur, Lost Highway, et al) that suggests they’d be receptive to interesting creative work. Does the assumption that they’re railing against ‘the man’ still ring so true that advertisers don’t even bother?

It seems unlikely, especially when you consider that some of the most powerful and memorable TV ads date back to the 90s, when Gen X was ostensibly at its coolest: Jonathan Glazer’s iconic Surfer ad for Guinness; the unforgettable launch of PlayStation; that still-terrifying Belly’s Gonna Get Ya Reebok spot.

The real reason Gen X is being ignored is likely down to a number of things, but mostly that age-old infatuation with youth held by brands, marketers and, indeed, most of society. It’s also pure laziness: in an era where social media algorithms are attuned to target users by age, they sell to us according to if we’re under 30 (youngish, hip-leaning, sports-casual); over 35 (either soppily maternal or desperate spinsters seeking fertility tests, if female); or over 50 (hapless dad-blokes, incontinent).

Clearly, these distinctions are reductive at best, insulting at worst. According to Anything But Grey, a consultancy “catering for brands seeking to engage a 50+ audience” (and staffed “of the age group, for the age group”), nearly 90% of people over 55 claim they feel unhappy with the way advertising represents them.

“Every single time somebody pigeonholed me I’ve been ignored, misread or badly typecast – so as a working-class woman who’s turned 50, being in this industry and also being a blanket bucket to target market is absolutely fascinating,” says Vicki Maguire, chief creative officer at Havas London. “When a brand says, ‘We want to talk to Gen Z’, it’s going to fail, because you cannot use those sweeping terms anymore. But you’d be surprised how many briefs we come across like that.”

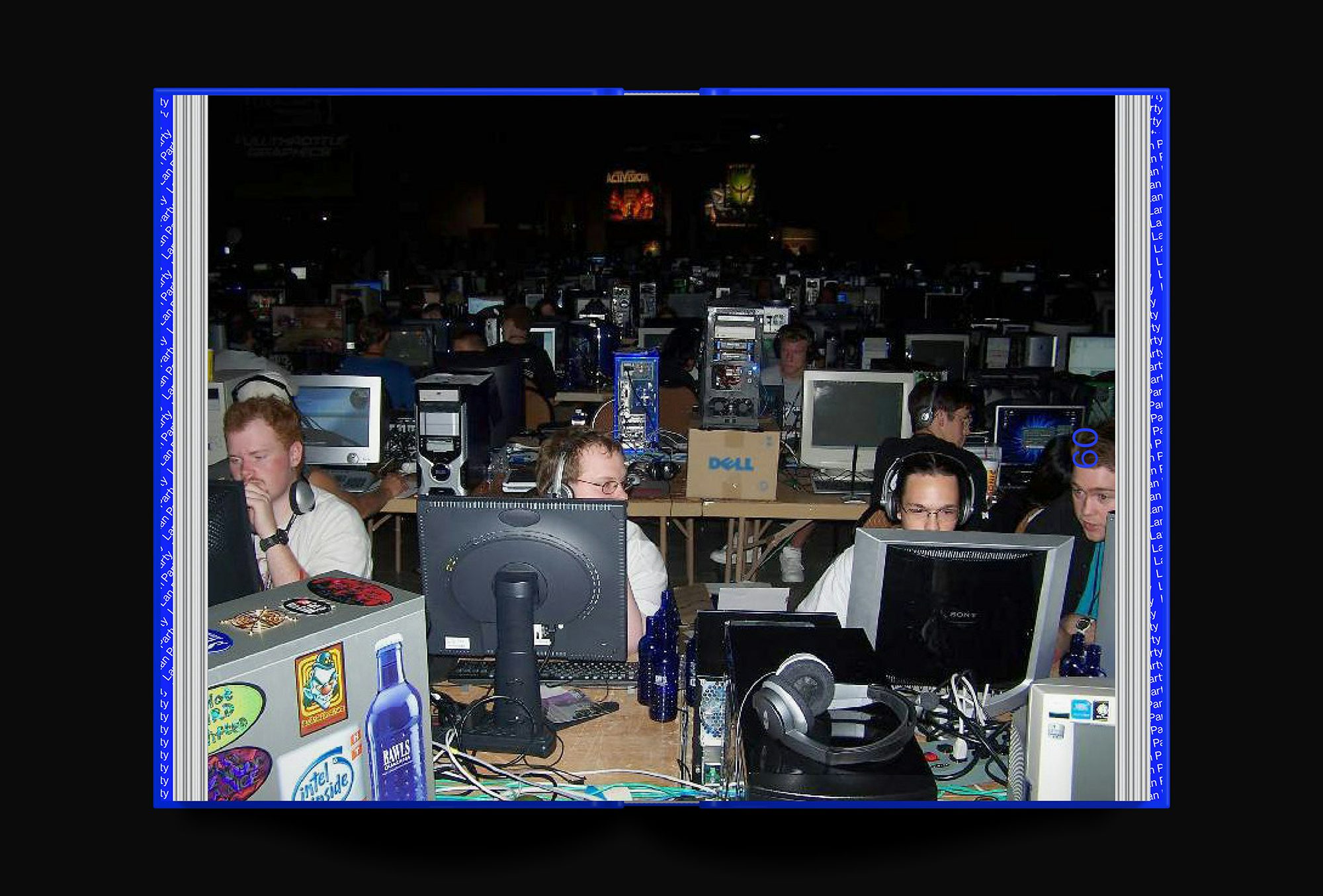

Or, unfortunately, we wouldn’t be surprised: the most cursory search for, say, ‘millennial branding’ yields countless ‘thought leadership’ pieces or case studies on how best to target this apparently lucrative (albeit enormous, wide-ranging) subsection of mostly 30s people. But it’s telling that you’re hard-pushed to find any such pieces about speaking to Gen X. Brands are “missing a trick from a business point of view, because we are the generation with money”, Maguire points out. “We’re also the generation that’s been brought up on change. ‘Digital native?’ Fuck off. I was there when it started – you can’t get more native than that.”

Mark Elwood, executive creative director at Leo Burnett, points out that while “we don’t hear much about brands targeting Gen X, that doesn’t mean they don’t”. He says one reason we don’t hear of brands or marketers actively speaking to Gen X is because it’s far harder to define than, say, millennials.

We’re the generation that’s been brought up on change. Digital native? Fuck off, I was there when it started

“Our obsession with generational marketing started with millennials, and out of that grew this manufactured media war with boomers,” he says. “But if you think about the likes of Apple, Netflix, and Amazon, Gen X have been supportive subscribers to the world’s biggest brands as they’ve been growing up, so they’ve been intrinsically linked to them anyway. You don’t have to directly target them because they’ve already been early adopters of those kinds of brands.

“For marketers, Gen X is much harder to define than Gen Z or millennials because they’re the mainstream,” he continues. “They sit in the middle, so overall, targeting can be quite reductive. They also straddle analogue and digital, as well as Labour and Tory governments – they’re much less of a clear target to put on a brief, and they don’t sit where marketers want people to.”

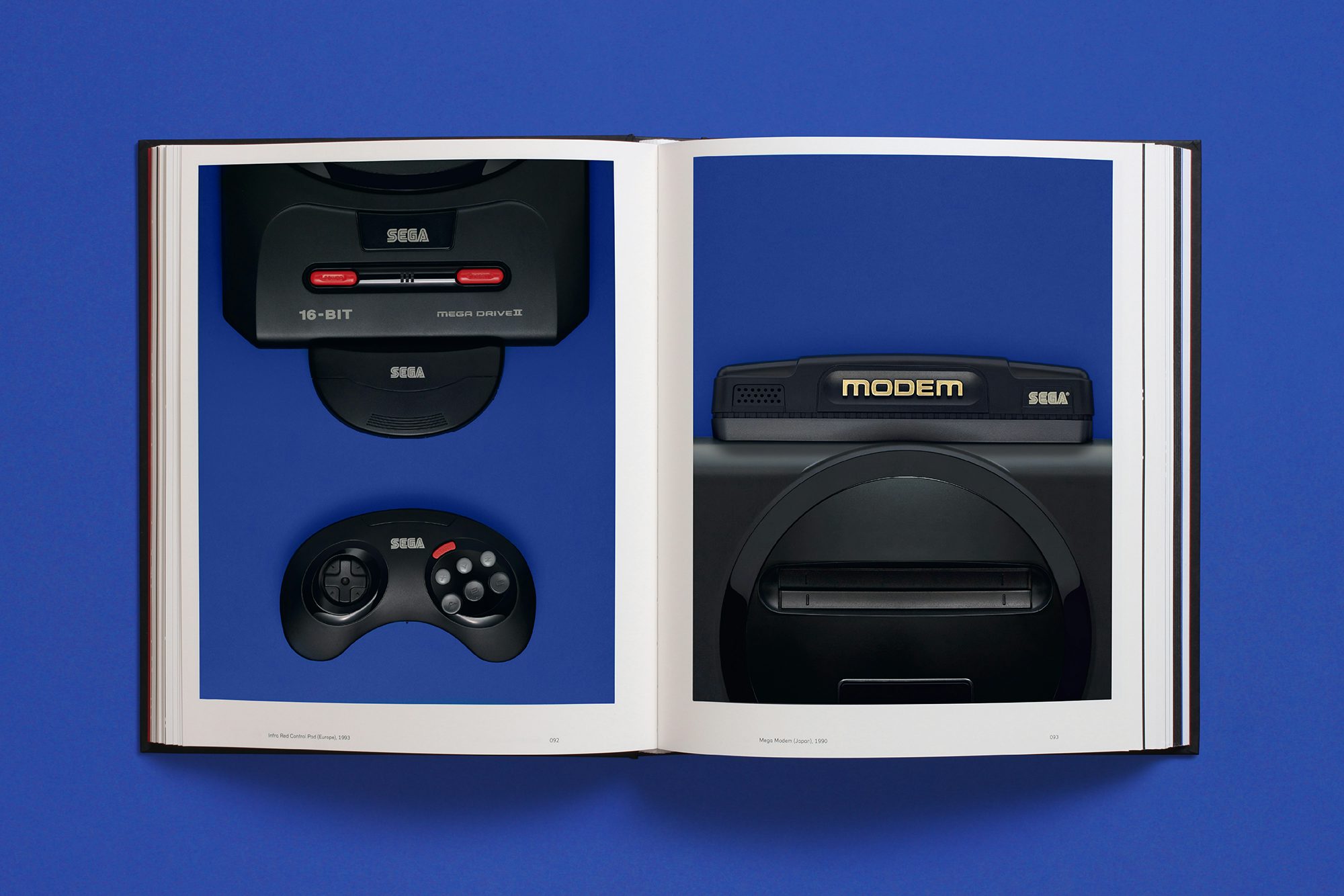

One area in which Gen X hasn’t been forgotten is in a certain strand of nostalgia-tinged artefacts – books about things like the Sega Mega Drive or Pulp, for instance. But art director Darren Wall, co-founder of Thames & Hudson visual culture imprint Volume, wasn’t thinking about age when he helped conceive such titles. He just wanted the books to show things that would be new to even the most diehard superfans.

Wall says that having “unwittingly published a lot of Gen X-friendly books”, what’s become clear is the marked difference in how young people today present their identity to the world. “Gen X grew up in an analogue age – you knew who someone was by the book or CD collection they were displaying. I don’t think I really knew about my friends’ political persuasions,” he says. “In the 90s, it felt so important to talk about what you liked – I don’t think people really do that anymore.”

In the 90s, it felt so important to talk about what you liked – I don’t think people really do that anymore

Indeed, even in the early days of MySpace you’d show the world who you were by the bands you aligned with. On social today, that’s been largely replaced with preferred pronouns and neurodivergency acronyms.

This is even evident on TikTok, Elwood points out: pretty much anything signposted as Gen X is based around music. As such, ads that subtly speak to Gen X often do so through song choice, such as Leo Burnett’s 2020 Welcome Back campaign, celebrating McDonald’s reopenings with Mark Morrison’s 1996 hit Return of the Mack. “It’s cool for a new generation, but it’s also quite cleverly speaking to Gen X,” says Elwood.

The books Wall publishes harness that idea of identity as based in cultural tastes, elevating things like Pulp’s album, This is Hardcore, into a realm that’s as much about reverence and beauty as nostalgia. “The magic of the books is in picking something that means a lot to somebody and delivering it to them as it would be in a Tate exhibition – it would be taken that seriously, with that amount of celebration, and that level of production,” says Wall. The book, as an artefact, brings things full circle: you might have given the CD to Oxfam years ago but you can still surround yourself with an object that says something about you.

“I heard a quote about Gen X: ‘This generation is never going to let go of their toys,’” says Wall. “I thought that was really good, because we grew up in such an analogue, physical time, and things were genuinely great – the music, the movies…. We were also relentlessly marketed to.”

That ‘relentlessly marketed to’ bit is perhaps most telling: now that Gen X are no longer Argos catalogue-circling kids or Metz-quaffing youth (“beware the Judderman, my dear!”), marketers seem to have forgotten about them.

Clearly, brands really are missing a trick here – and not only because they’re ignoring many of the people with the most to spend. By pitting youth against experience in their targeting, they run the risk of creating comms that are actually “damaging for your brand”, says Maguire. “Engaging in a meaningful way means not lumping me into an age bracket that’s shorthand for death and pissing myself. As a woman going through menopause now, some of the stuff I’m getting served and the ways people are talking to me is really shocking. When they do get it, they have my money – they have my endorsement.”

There’s certainly a sense that – especially for women – an invisibility cloak sets in past 50, when brands don’t even see you let alone speak to you in meaningful ways. An ad for Alpecin caffeine shampoo makes this painfully clear by literally whispering, “It’s especially popular with women over 40” – as if ageing were so horrific we dare not speak of it out loud. As one Mumsnet user succinctly phrased it, “it’s advertising negging”.

Brands need to know what they stand for. If they’re clear on that, people will find them, regardless of age

Decades back, maybe it was indeed a good idea to sell Saga holidays to

50-year-olds, but things are different now – to paraphrase a Stewart Lee gag, being over 49 doesn’t relegate you to chair-based exercise. We see it time and again in famous people: Madonna’s 2023 greatest hits world tour; Jennifer Coolidge hitting her career peak at 61; Davina McCall’s sterling work reminding Channel 4 viewers that even hip, effervescent women like her experience the menopause.

“Brands that are doing it badly still see 50-year-olds like we did at the turn of the century, but I can just look out the window and see Gen Xers in Converse and Nike, not comfortable brown suede shoes,” says Elwood. “As much as brands need to know their audience, they need to know themselves – what they stand for and what image they’re presenting. If they’re really clear on that, people will find them regardless of their age.”

It’s telling that the kind of imaginary consumers dreamed up in agency boardrooms (‘she’s a bit Carrie Bradshaw but from Dulwich, owns a few cats and enjoys West End shows with her girlfriends’) isn’t ever a person that’s either in that boardroom or one who anyone in there knows in real life. These two-dimensional caricatures stand against anything that’s truly creative, and as with arbitrary Gen X/Y/Z pigeonholing, speak to precisely nobody that really exists.

The brands that resonate most with Gen X, says Maguire, are those that “don’t just talk to us like an age group who needs to put the font size up”. She points to Apple, “who flatter us with the fact that we were there buying the first iPod”.

Similarly, she says, when First Direct started out, its average consumer was 21–25, now it’s 45–55: “They haven’t needed to drop us to go and stalk the flame-throwing T-shirt-wearing youth of today. They have come with me through my life.”

To achieve both longevity and a sense of age-agnostic communication that speaks to real people rather than boardroom-constructed fictions comes down to “selling on attitude, not age”, says Maguire. “I love that New Balance line, ‘Worn by models in Paris and dads in Ohio.’ That brand is not afraid of being ubiquitous because it will have a style in absolutely every point – it’s giving you licence to wear.

“I love seeing 70-year-olds wearing Patagonia walking their dogs, and I love seeing Japanese fashion students at Central Saint Martin’s wearing it. Those brands that transcend age and talk to attitude instead are the ones that are meaningful and will survive. Brands that are confident in their own ‘purpose’ – I hate the word purpose – and their own being invite like-minded people in rather than having to sell. They’re magnets rather than pleaders.”