How design can stop prisoners reoffending

We take a look inside InHouse, the social initiative that’s a “different kind of record label” – with the reoffending rate of participants at less than 1%

Based on principles of co-creation and founded with the very real spectre of adversity in mind, InHouse records was established in 2017 as a “different kind of record label” that acts as a social initiative with one main goal: to prevent reoffending. It was created by Neil Sartorio and Judah Armani, and came out of Armani’s interest in the use of design in prisons while studying at the Royal College of Art.

Billed as a “rehabilitative record label for change”, InHouse has been operating in and out of UK prisons across the South East of England over the last five years, and saw Armani bring together his background working in both design and music. Initially, the plan hadn’t been to focus on music at all – in fact, it was something he’d wanted to avoid. “I was really aware that the industry is unregulated in the sense that anyone can become a manager, anyone can do this,” says Armani. “Sometimes it can be great, and sometimes it can be toxic – the last thing I wanted was for the guys to leave an environment of crime and go into a toxic environment that’s in some ways worse.”

Armani held aspirations of using design to “facilitate society to make better choices”, he says. “I was really questioning the rationale of where design can play a role in things like the criminal justice system. It started with the premise of ‘can design contribute to reducing reoffending’?”

Armani initially spent a lot of time visiting prisons to ”understand a little bit about the guys there and the different stakeholders”; offering things like lessons on “creative thinking” for free. He proposed the idea of working with a different group of people each week to work collaboratively on a project. “In prison, you have a choice if you want to go to work every day, or if you want to go to lessons every day, or if you just want to sit in your cell every day, and education and employment are massively unengaged with,” he explains.

We needed to explore ways of how we can bring creativity to those that have had ‘creativity poverty’

“A lot of people that were coming to the sessions I was running weren’t actually going to employment or education, so the prison decided to take a risk on me. It didn’t cost them anything; and it meant that their hardest-to-reach guys – guys that were just never leaving the wing – were engaged for a couple of weeks.”

For the most part, Armani’s classes were about giving participants agency as much as teaching people things. “Most of the guys have never grown up with that ability to rewrite their own path, so asking them ‘what would you want to do if you could do anything in prison?’ actually wasn’t a helpful thing to say, because all they could think about was what they had already experienced. So they’d be saying, ‘can we just do laundry but with nicer biscuits?’ We needed to explore ways of how we can bring creativity to those that have had ‘creativity poverty’, if you will.”

Armani looked into indicators of how likely prisoners are to reoffend, and found that the key indicator of whether someone’s not going to go back to prison “isn’t getting a PAYE job, or getting securely housed, both of which actually, quite frankly, make it a 50/50 chance [of reoffending]”. It didn’t have much to do with people studying English or maths, either. What was missing, he says, was “the life admin skills – the core competencies of communication, accountability, adaptability – because they were not present in the lives of the guys as they were growing up. They didn’t have role models that would communicate in different ways, and often didn’t have consistent parents or caregivers”.

As such, Armani had decided that the premise of whatever form the project would take would be around ‘social capital’, and working on something that helped embed that in people. Through discussions with prisoners, it became clear that it was a “two horse race” in terms of what people wanted to focus on – either fashion or music.

Music ended up winning, and Armani reckons that’s in no small part down to its ability to help people express a narrative, and work within language and frameworks that were both familiar, and which helped them push what they talked about and how they talked about it. Ultimately, it gives people a chance to rewrite their own narratives.

The next step was planning how to “build in the core competencies of social capital” into music. “With every task, whether you want to be a rapper, or producer, or a manager, or an artist, there’s certain things you need to do if you want to put on a gig or if you want to record some music,” he explains. “There are certain tasks that you need to do every week, and those tasks need to be communicated, so we explore how you’re communicating to different audiences. The point is, that’s a new network that they’re part of within music, and that in turn speaks to and is a part of a range of [other] networks. My thinking was, if you could be a part of five networks, you don’t go back to jail.” It worked: today, the rate of reoffending for those who’ve been part of InHouse records is less than 1%.

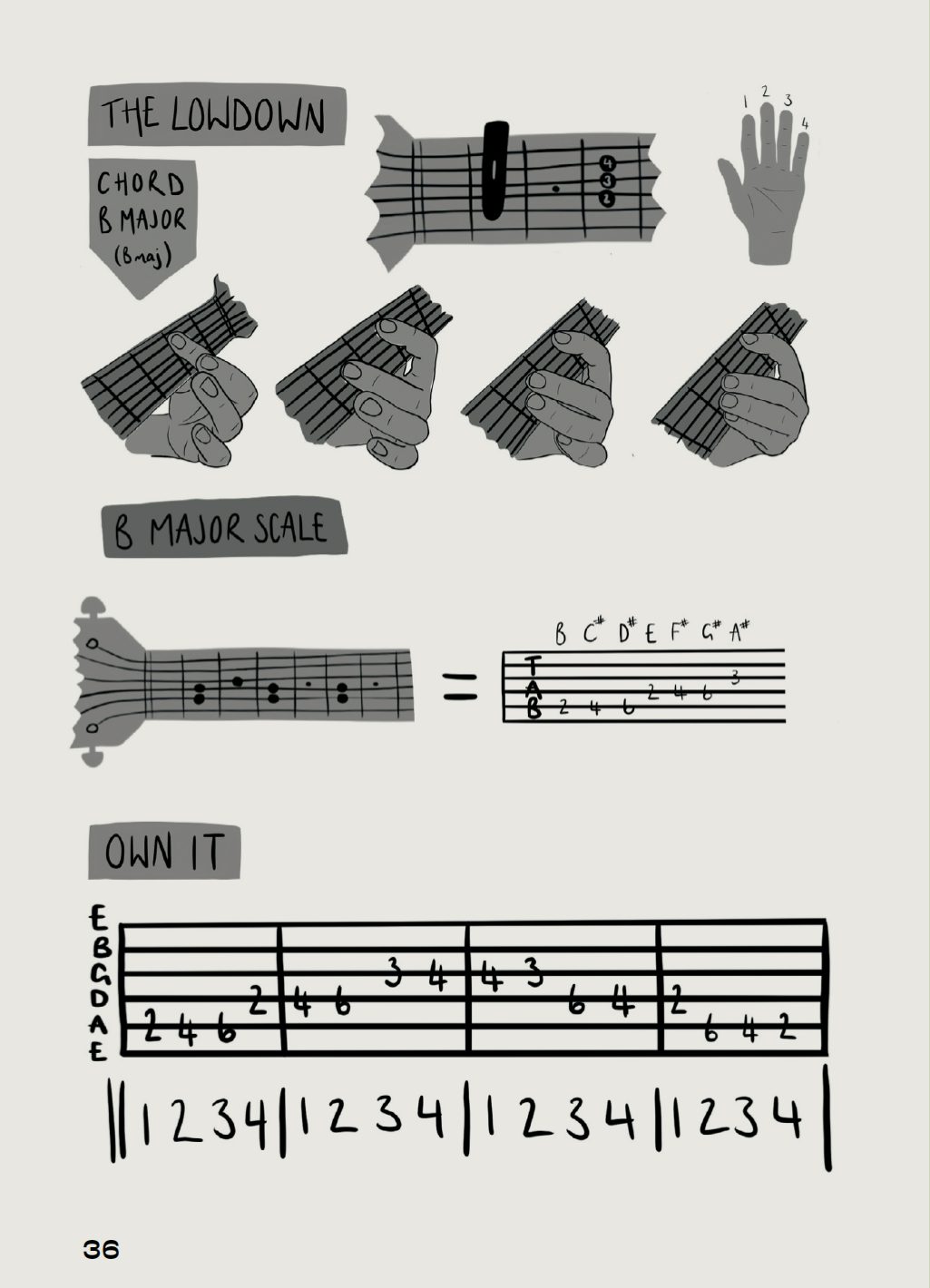

The process of getting involved starts with prisoners being put on the waiting list for their place with InHouse (Armani says the programme is usually 350% oversubscribed). They’re given a copy of the programme’s zine, Aux, which started life during the pandemic as an alternative to tools like badly photocopied wordsearches that were being disseminated in a lacklustre attempt to alleviate the boredom of people being in their cells 24/7 during lockdown. The zine features articles that aim to be useful once people get on the programme, covering things like the writing process for aspiring rappers, storytelling and so on.

While it was created weekly during Covid, designed by InHouse records’ Hannah Lee, who taught graphic design at HMP Elmley in Kent prior to the lockdown, the mag is now quarterly, and uses her design and curation as a framework but with input from guest editors and designers, as well as from the prisoners themselves.

“We’re working with a predominantly neurodiverse community, so traditional books and things just aren’t helpful for a lot of people,” says Armani. He worked with a diverse group of experts and neurodiverse people to co-create a series of 13 learning cards that form a weekly curriculum for the programme which is Arts Award accredited, meaning people can work towards bronze, silver, or gold Awards.

When it comes to actually making music or being involved in other aspects of the process, such as management, the workshops take place in a studio setting with things like a laptop, instruments, some people being recorded, some people who are writing, and some people working on things like strategy. In the first few sessions, the staff facilitator will sit down with the prisoners and get to know a bit about them and start to explore what they’re interested in – “maybe you want to be a writer, maybe you want to be a producer, manager – and it’s totally fine for them to say ‘I don’t really know yet’,” Armani explains. “We’ll create a little bit of a mini plan before we can have a bigger plan – we try to keep the plans really short, because they might be moved to another prison.”

He continues, “If you like rapping, let’s make a song – but in order to make a song, you don’t want to waste recording time, so you’re going to need to have it perfected before you record it. And in order to do that, you need to write it: so come up with an idea next week, write it the week after, practise it, and the week after that, record it – that’s a four-week plan.”

If we want to get on with life, we need to work out a way where the people that wind us up, bring out the best in us

One of the big things Armani says he notices is how the participants’ songwriting changes over time: it’s made clear to them that the best writing comes from what you know, but with the caveat of not glorifying things like drugs and crime. “We might support them in terms of telling a story in a different way, but not change it, so that they grasp their own practice and their own understanding,” he explains. “To get to the point where they’re recording a song is usually a seminal moment where they’ll be like, ‘I’ve never actually achieved anything, is this CD mine?’ Yes, and by the way, you’ve just completed the first level of an Arts Award programme, so if you want to carry on, in another couple of months you’ll get a bronze award. Let’s just keep going with this process, and maybe by the end of the few months, they might have an EP.”

Other strategies might include working towards a gig, where friends, family and prison staff are invited to see a showcase performance. Some participants will be working on the organisation of those gigs, others on their performances.

While not every record is released physically, the participants are involved in the design of their record – be it for a digital thumbnail or a CD. Some of the designs are assisted by Masters students at the RCA, who work with the creators to play around with how to visualise what they want to get across with the track or record. The logotype for InHouse records itself uses the font Millennium.

At the heart of the programme is instilling ideas and skills around creativity and collaboration. The majority of the InHouse cohort are young black males, “because for whatever reason, [prison programmes] are just not able to connect with them,” says Armani. But how do you teach collaboration? “That is the fundamental crux of all of this,” says Armani, “because that’s why networks and associations are important. We have to get to a place where we work with people we don’t like. It’s easy to work with people you like … fundamentally, in the prison system, they’re not so bothered about collaboration – they’re bothered about individual learning. But society doesn’t work as independent narratives – it’s an interdependent narrative. And if we want to get on with life, we need to work out a way where the people that wind us up, bring out the best in us.”