Richard Holman on the value of the unexpected moment

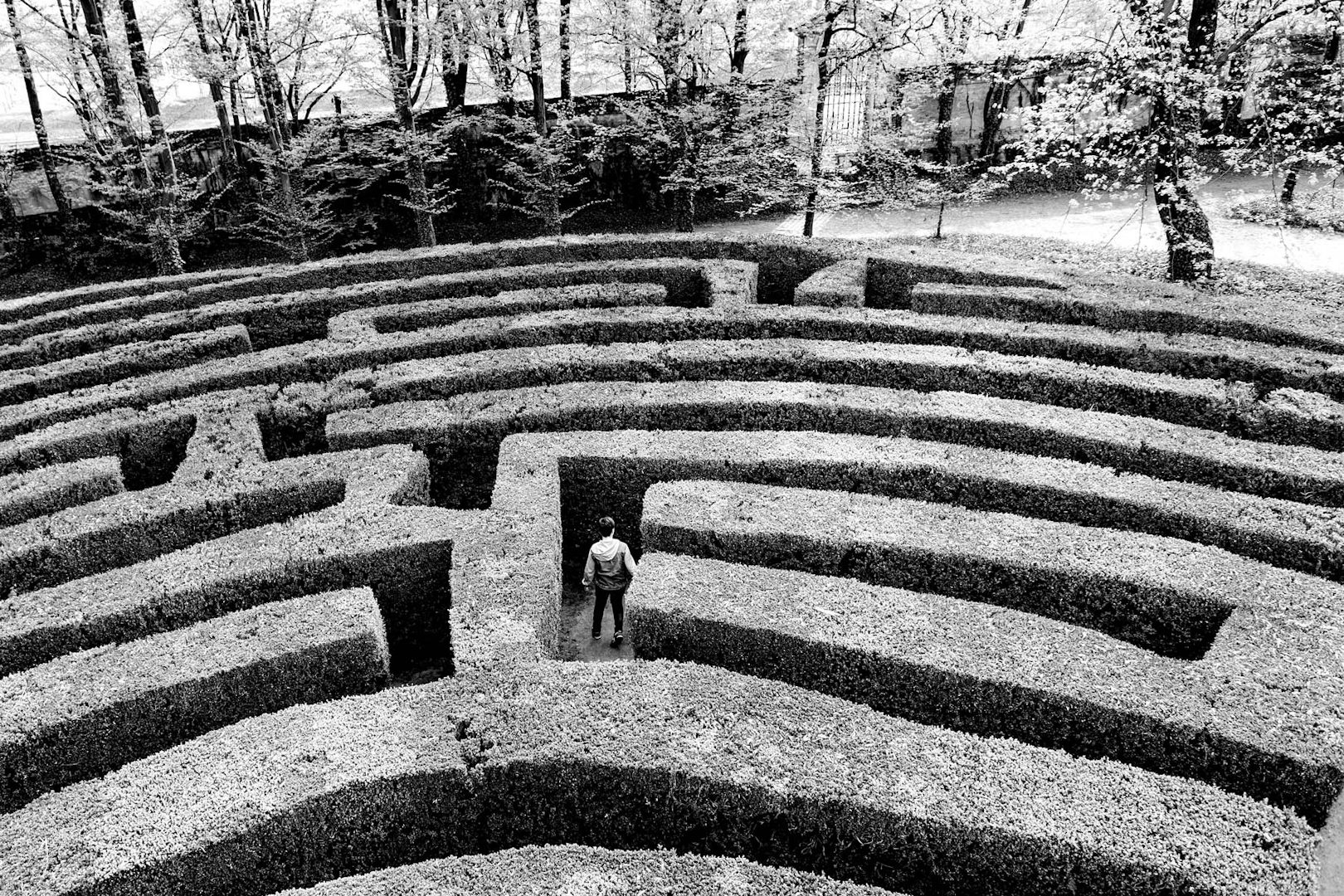

Wrong turns and unpredictable moments are a part of every creative journey, yet we rarely like to examine these in full, preferring to give the impression that everything is in our control. But, writes Richard Holman, these accidents are vital

Few of us would admit to being without a clear sense of direction. The imperative to know where you’re heading professionally begins early on. When I was an intern – which was so long ago the term ‘intern’ was yet to be coined – a kindly and long-in-the-tooth creative director took me aside and asked me about my five-year plan. Five-year plan? I could see just about as far as the weekend, and even that was kind of hazy. Embarrassed, I hesitated, mumbled something incoherent, and asked if he’d like another cup of coffee.

Once all those lunch runs and late nights working for a pittance paid off and I landed a job as a creative, the pressure to plan became even more intense. Every shoot required a shot list, a storyboard, and a pre-production meeting. I was taught to anticipate, to mitigate the unexpected, to drill accident out of the creative process.

This desire to know where you’re heading is understandable, especially when there are risk-averse clients around, but does it come at a creative cost? The photographer Dorothea Lange, renowned for her work in the dust bowl of America during the 1930s, especially her photograph Migrant Mother, once said: “To know ahead of time what you are looking for means you’re then only photographing your own preconceptions, which is very limiting and often false.”

Genius lies not in the things they plan or envisage, but in their ability to be alive to the possibilities of every moment

And the more you dig into the lives and work of some of our greatest creative minds, the more you discover that their genius lies not in the things they plan or envisage, but in their ability to be alive to the possibilities of every moment, and having the courage to seize upon the gifts of chance, even if it means a late change of direction.

The films of David Lynch are so distinctive and dreamlike that it would be easy to conclude they could only be conjured from someplace deep within his own imagination. Yet his recent memoir Room to Dream is full of tales of creative opportunism, like the moment on the set of Twin Peaks when actor Richard Beymer had been given a stiff pair of new shoes by the costume department. As a kid he’d tap danced, so he was tapping away in a corner to loosen the shoes up. Lynch happened to notice this and came over and told him he should dance in the next scene. Beymer was concerned: “But David, in the next scene I’m talking about murdering someone.” Lynch replied: “It will be great! In fact you should dance on your desk.” And so one of the most emblematic moments in the series was born.

Orson Welles felt the same way. As he once put it, “The greatest things in movies are divine accidents. My definition of a film director is the man who presides over accidents. Everywhere there are beautiful accidents … they’re the only things that keep a film from being dead. There’s a smell in the air, there’s a look, that changes the whole resonance of what you expected.”

To rigorously adhere to your vision for a project is to allow yourself to be hemmed in by the boundaries of your own imagination

Being alive to the moments beyond your own orchestration is an approach employed by artists in other genres too. Jeff Tweedy of the band Wilco describes in How to Write One Song how he often relies on a “mumble track” if he’s struggling to come up with lyrics. He sings anything, gobbledegook, just to get the melody down. Yet when he listens back to the recording, he often finds he starts to hear those sounds as words, and soon lyrics emerge which he feels are way more interesting than anything he could have consciously written.

Hilary Mantel, the double Booker prize-winning author, has written how, “If you think of any worthwhile novel … no one is clever enough to do it. You have to take your hands off and see what shapes the story forms…. The task is to get out of your own way.” A fellow novelist, Andre Dubus III, puts it a little more bluntly: “Characters will come alive if you back the fuck off.”

To rigorously adhere to your vision for a project is to allow yourself to be hemmed in by the boundaries of your own imagination. If you want to achieve something greater, something beyond the realm of your own ability, then you have to give yourself up to what Welles understood to be “the magic of accidents”.

One way to do this is to deliberately cede control. Karl Ove Knausgård is widely acclaimed for his autobiographical novels. He has described how he knows his writing is going well if the words appear on the page without effort, as if he were a reader of the text rather than its author. To induce this state, he rises early to be in the space between wakefulness and dreams, chooses an ordinary word like ‘son’ or ‘tooth’, then writes about that word without constraint, allowing himself to go wherever his unconscious chooses.

The painter Maggi Hambling adopts a similar process. Like Knausgård she wakes early. Before she’s dressed or had breakfast she makes a drawing with an ink dropper using her less favoured left hand. There’s no intended subject, she simply allows her hand to go wherever it wishes. The drawings created by this accidental process have inspired some of Maggi’s most successful paintings.

It’s all to do with ‘mindful making’, a technique of adhering to a plan while being alive to the unanticipated possibilities of the moment

So how does this technique work if you have clients with expectations of how a particular project is supposed to end up? It’s all to do with ‘mindful making’, a technique of adhering to a plan while being alive to the unanticipated possibilities of the moment. To illustrate, let’s take a trip to outer space.

Apollo 8 was the first manned mission to orbit the moon. Among their many tasks, the astronauts on board had been briefed by NASA to photograph the lunar surface. On their fourth orbit, mission commander Frank Borman rotated the ship by a few degrees. As he did so, astronaut William Anders caught sight of something out of a side window that took his breath away: the blue pearl that is our planet, slowly appearing above the barren, grey, lifeless moon.

Even though it was outside their strict schedule, Anders grabbed his highly modified Hasselblad and fired off a few quick exposures. One of them was to enter history. Earthrise, as it became known, heralded the dawn of the environmental movement. For the first time we could see how beautiful and how lonely our planet is amid the vast blackness of space. An unbidden moment of impulsive creativity which changed everything.

Storyboards and shot lists have a role to play. Maybe even five-year plans too. But be careful not to adhere to them too religiously, or you’ll only ever end up where you were expecting to go.

Richard Holman is a writer and coach, richardholman.com; Top image: Shutterstock