Takuma Takasaki on Perfect Days and the art of storytelling

The chief growth officer at Dentsu in Japan talks to us about the relationship between narrative film and advertising, and his intuitive collaboration with Wim Wenders on his Oscar-nominated film Perfect Days

In 2023, prolific photographer Daidō Moriyama released a book of images celebrating an overlooked constant in the built environment: public toilets. “It may sound as though I am exaggerating, but no other photographer has used public restrooms in Japan as much as I have,” he wrote in the book’s introduction, referring to the pitstops he made over his many years spent making images around Japan.

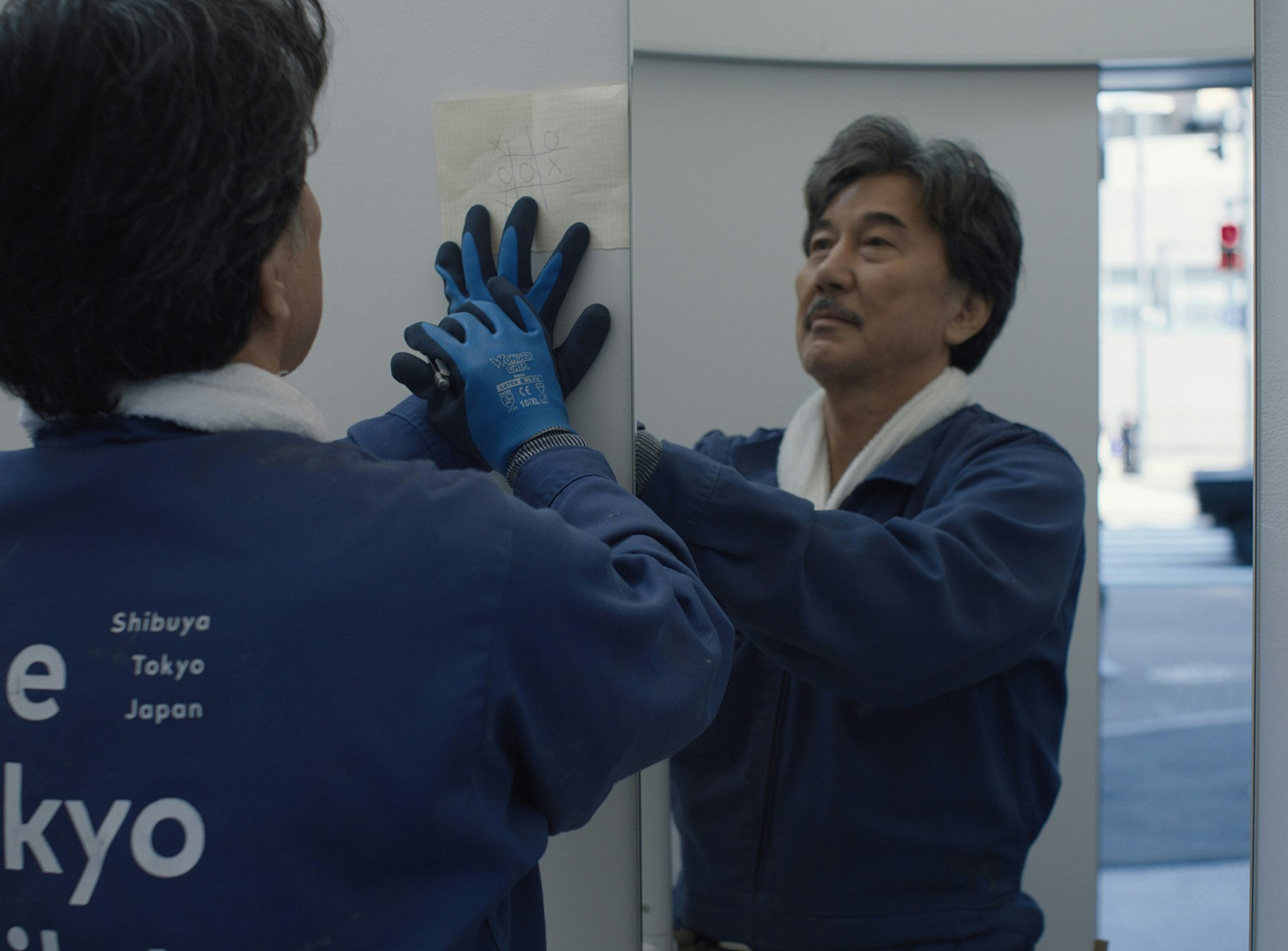

That may be so, but he has a fictional rival in Wim Wenders’ latest film Perfect Days: Hirayama, an unassuming, slightly enigmatic protagonist, who ritually photographs Tokyo’s urban plant life in between cleaning jobs for The Tokyo Toilet.

The Tokyo Toilet is a real initiative compromising 17 public restrooms scattered around Tokyo’s Shibuya district, each one individually designed to transcend its practical function by doubling as an architectural point of interest. Among them are Kazoo Sato’s igloo-like design and Shigeru Ban’s pastel-hued glass box that turns opaque upon locking. The Tokyo Toilet was completed in time for the 2020 Olympic Games, but with the occasion partly stalled by the pandemic, these mini design marvels never quite had the celebratory launch they deserved, leaving their appreciation outside of Tokyo largely confined to specialist architecture publications.

Yet this patience has now been rewarded. In the hands of Wim Wenders – the filmmaker behind Wings of Desire and Paris, Texas – and Tokyo-based screenwriter Takuma Takasaki, who is also a decorated advertising creative director, producer and novelist, The Tokyo Toilet initiative is finally getting its moment in the sun through the lens of film. “We wanted to make four short stories,” explains Takasaki via an interpreter, Shion Ebina. Yet after approaching Wenders to direct the project, the German filmmaker suggested turning it into a feature-length film instead.

The outcome, Perfect Days, has been nominated in the Best International Feature Film category at the Oscars – a feat only possible because as Wenders has stipulated, it is not a film about toilets. It is about the human condition, shown from the perspective of Hirayama, who tends to the toilets with as much care as he tends to his soul with music, literature, and plants.

Wenders was drawn to the project partly because it was an opportunity to reconnect with a city that he sorely missed, having been unable to visit Tokyo for over a decade. But it was also his appreciation for architecture and art, which met harmoniously in this particular project.

It’s almost like he is my mentor. He’s my friend. He’s almost like a father figure for me. So ever since we met, I felt like we were syncing up

The Tokyo Toilet was spearheaded by Koji Yanai, senior executive officer of Uniqlo’s parent company Fast Retailing Co (who incidentally wrote the afterword for Moriyama’s photo book). Though Yanai served as a producer on the film, the project’s affiliation with The Tokyo Toilet was never meant to interfere with the creative process. It was purely meant to be art, Takasaki explains. “We didn’t really brief [Wenders] with what we were looking to have.”

“When I was a student, so that was some 30 years ago, I watched his films,” Takasaki recalls. Immediately struck by his work, Takasaki was inspired by buy his own 8mm camera – which he still has – and began to make his own films. He learned much of his own craft by immersing himself in Wenders’ filmmaking philosophy from afar, which also proved fruitful when they collaborated on the Perfect Days script. (For his part, Wenders described Takasaki as “a great sparring partner”.)

“It’s almost like he is my mentor. He’s my friend. He’s almost like a father figure for me,” explains Takasaki. “So ever since we met, I felt like we were syncing up. There was a lot of commonalities between us, and he also said that to me as well. So even if I didn’t receive detailed explanations, Mr Wim Wenders would say something like, ‘maybe we can get rid of this line’, and then I could perfectly understand the reason why he would say something like that.

“Or I could say something about ‘how about changing the order of the sequences?’ and then he gets me instantly. So we didn’t have to have a really detailed discussion. We could understand each other very well, and that played a really big part in this filmmaking.”

He says that their parallels were noticed by Donata Wenders, a photographer as well as the director’s creative and life partner, who also created the figurative black and white sequences peppered throughout the film. “She mentioned this quite often – she said that she sometimes gets confused, and then she can’t really tell us apart in our comments [on the script]. So I think that’s how you know how similar we are.”

Takasaki and Wenders worked together in English with the help of an interpreter, and the final script was delivered in Japanese. They came together across languages, cultures and filmmaking traditions, guided by a shared mindset when it comes to storytelling. “The Japanese ways of making films, the German ways, Mr Wenders’ past methods … none of these matter,” Takasaki said on a follow-up email.

Hirayama is described during the film as not much of a speaker, but a good listener, and accordingly, the film is a quietly poignant study of our individual place in contemporary society – what fulfilment looks like, and how small interactions can add up to be far greater than the sum of their parts.

What cannot be explained with words is something that should be turned into a film – that’s what he said to me

While there are many layers to the story, Takasaki says there are several broader themes that underpin the narrative, such as the passing of time – a universal fact that everybody must come to terms with. And, relatedly, the tension between movement and statis in Tokyo, “a city that continues to grow” while the people in it might not necessarily be inclined to move with it. “In the modern world, people tend to think of growth as the purpose of living,” Takasaki says. In some ways, Hirayama embodies a kind of resistance.

These elements provide an undercurrent rather than being front and centre. When Takasaki spoke to Wenders about the approach to the script, the director told him: “‘We shouldn’t be able to verbalise this; we shouldn’t be able to put it into words. If we can put it into words, there is no need to turn it into a film’, he said. So what cannot be explained with words is something that should be turned into a film – that’s what he said to me.”

This philosophy seems to have shaped the script itself, which is light on dialogue, particularly in the beginning. “For the first 30 minutes, there’s virtually no lines, and then that first 30 minutes works for everybody around the world to understand this character Hirayama, because it doesn’t use a language.”

It is proof of how devices such as images and music can carry messages and tell stories without a single word being uttered – a combination that’s been effective in other arenas, among them advertising. It’s something Takasaki will know a thing or two about, as a veteran of the advertising industry and chief growth officer at Dentsu (a role he admits has earned him an unusual level of freedom), who has previously worked on campaigns starring the likes of Robert De Niro and Richard Gere.

However, he sees a distinction between these forms of communication, noting that with advertising, “it’s about sending out a single-minded message, and it’s really about how to proliferate that single message to as many people as possible. But on the other hand, for films, when more people watch it, then you know it could be perceived in so many different ways, so people are entitled to their own interpretation.”

He doesn’t like “advertising-orientated films”, but sees how advertising could become increasingly cinematic, since the field is constantly changing with the times, as he puts it. And although advertising and narrative filmmaking generally serve different purposes, he recognises a commonality between the different parts of his career – commercial projects, screenwriting, writing novels, “and that is that we are portraying human beings”.

“That goes for novels, that goes for films and that may be the case for advertisements as well. But what makes them different is that for novels, we won’t be able to use music for example. At the same time, there are things that only novels can do, there are things that only films can do.”

One of his novels is in the pipeline to become a film, though he is happy just to be the “originator” of the story rather than the scriptwriter for the adaptation. “There are a couple of short stories I’ve written in the past so I’m trying to turn them into movies or films.” All of it feeds into a multifaceted practice that helps him appreciate the finer details of each part of his creative life – an appreciation not unlike Hirayama’s. “If you do different forms of expression, you slowly start to learn what films are only capable of doing.”

Perfect Days is in cinemas now