“AI was always my target. It’s not something that popped up in my journey randomly,” says Refik Anadol, one of the foremost figures blending art and machine intelligence today. “Playing with games and computers at an early age, you know that one day, the machine can become your friend, your collaborator.”

It’s a philosophy that the Istanbul-born, LA-based media artist has maintained throughout his working life. “To me, AI is a tool that allows me to create a new collaborator that doesn’t forget, that remembers billions of points, and millions of whatever information I’m looking for, to be used as a pigment, as a form, as a sculpture, as a story.”

Anadol had been working with machine intelligence long before it spilled into the mainstream. He began to use computer programming to make art back in 2008, the year he says he coined the term ‘data painting’, and since then has worked at the intersection of visual media, data, and emergent technologies.

All the while he was meeting with pioneers in the fields of new media art, but also in the world of architecture, laying the foundations for the grand architectural interventions that his eponymous studio, founded in 2014, has become known for. “In the last eight years as a studio, we’ve worked with more than four billion images and trained more than 300 AI models, and that put us on the map.”

Anadol is all about big. His passion comes out in hyperbole. His installation projects are often on architectural scales, like the Sphere, the controversial Las Vegas building wrapped in the world’s largest LED screen. And then there are the gargantuan statistics attached to his datasets. For a lot of people, numbers start to lose their meaning after a certain point, but not for Anadol.

Of course, this is a medium that can create problems. It’s a medium that mimics intelligence, it’s a medium that will challenge us to question creativity

His boundless enthusiasm and big-picture thinking are perhaps what’s needed at this juncture in AI’s journey. Although new media artists have been developing algorithmic art for years, the mainstream arrival of tools such as ChatGPT, Dall-E, and Midjourney seemed to have uprooted a lot of the goodwill they had previously inspired.

He recognises the concerns but also believes there is a “hysteria” around AI. Seemingly a glass-half-full kind of person, he focuses on the possibilities. “Of course, this is a medium that can create problems. It’s a medium that mimics intelligence, it’s a medium that will challenge us to question creativity, it will challenge jobs and the purpose of many things in life – because it is a mirror for humanity. It will exactly reflect back who we are,” he says. Those who choose to “see imperfection in humanity bring that imperfection to AI”.

Plus, ‘AI art’ is an enormous umbrella term that obscures important distinctions between its different strands. One of the main ones is data. To be an AI artist in the past would have meant consciously delving into research and data science; now, with the accessibility of AI image generators, an AI artist can freely produce work without considering the origins and later uses of the data they’ve handled.

Anadol appears to be in the first camp. Though some of his works use publicly available data, he is also keen on collecting (and open sourcing) original data, enthusiastically recalling the time he lugged 50kg of gear around glaciers and ice caves. “We really love exploring nature, and I think this is [the] future, to be honest, for artists to really understand where data comes from. It’s not just a bunch of images.”

Anadol is aware that data – where it comes from, where it then goes – is at the heart of people’s concerns about the emergence of this technology. He hopes his new exhibition at London’s Serpentine Galleries, the product of years-long exchanges with artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist, can illuminate some of that process. The exhibition sees him unveil Dataland, a kind of research institution contained within an artistic one. The plan is to bring together experts in different fields, from neuroscientists to AI engineers, botanists to musicians, with the aim of creating “meaningful, purposeful experiences” and, crucially, making space for healthy discourse around AI.

While that goes on behind the scenes, in tangible terms the show will feature AI-generated images representing flora and fauna found around the world, which are paired with sound and even aromas. Shown on a laptop screen over Zoom ahead of the exhibition opening, the example images have a simple beauty about them, but of course Anadol builds his projects with scale in mind. “I think it will be a very meditative space to explore data archives.” He says that all of his exhibitions include a “process wall” to educate visitors, but he hopes Dataland will take that a step further to offer “a walk inside the datasets in the show. That will make, I think, people have more understanding of what’s going on.”

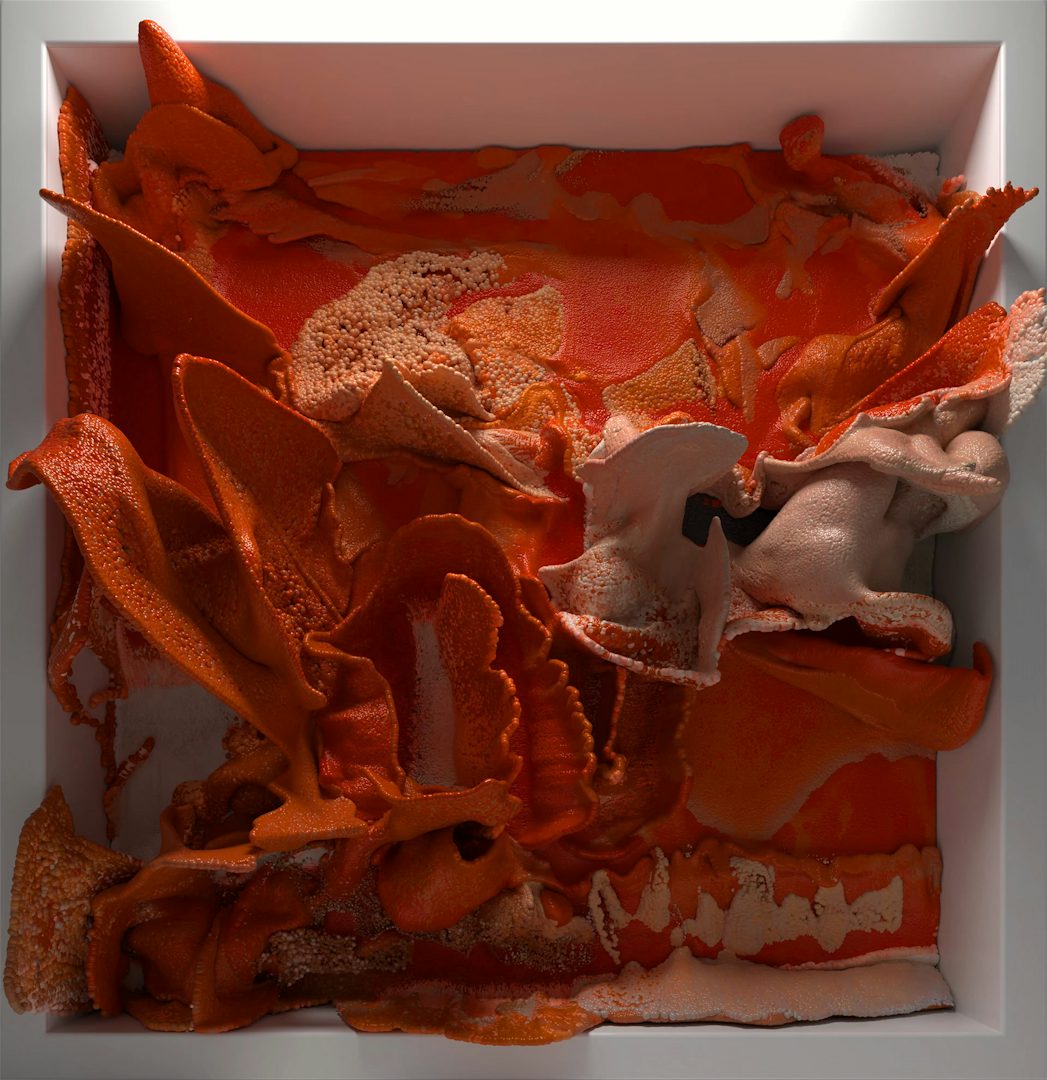

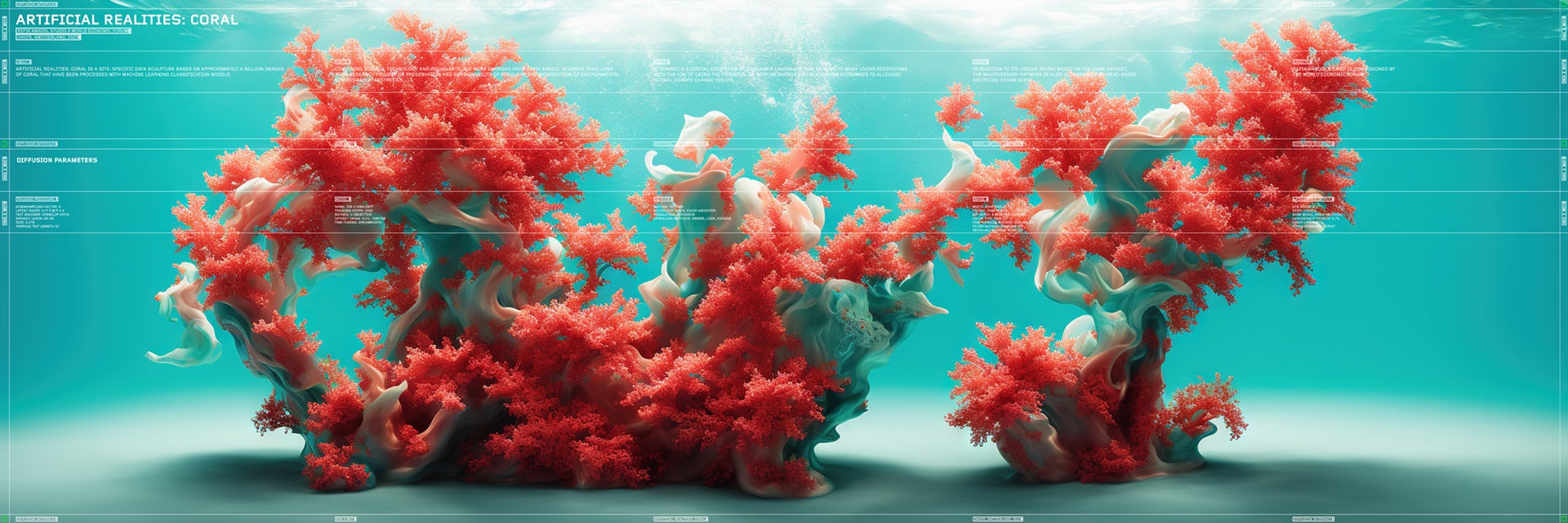

The show will also present his coral installations first commissioned by the World Economic Forum, featuring AI-generated simulations of coral reefs, many of which are at risk around the world. He notes that at the WEF, the project was well received by world leaders across political and geographic divides. “So even though it looks like shiny pixels, it’s beyond that – they can be very functional.” Though that’s perhaps to be expected: it’s hard to argue over the startling beauty of coral reefs and whether or not they should be protected. As with the increasingly spectacular and polished David Attenborough documentaries from the BBC, whether mesmerising images are enough to mobilise people will perennially be a point of debate.

These works have been designed not only to have artistic value but also a scientific function. Anadol says that the image archives built up by his studio are accurate to the extent that researchers can use them to reliably study and plot real species, using their Latin names. “I’m calling this field ‘generative reality’. I believe that AI will allow us to think about reality in a different context. The reality becomes an input, and it’s always like this for artists, but I think AI is something much more profoundly allowing artists to create realities,” he says.

It’s a step change for the studio, which has spent years creating hallucinatory, morphing pieces as part of the Machine Hallucinations series, among others. Now Anadol is looking to achieve something more specific, scientific – something that will remind people that, for all the technological advancements, “nature is the most intelligent thing we have”.

As such, the Serpentine exhibition is, in a way, a public-facing vessel for a research initiative, one in which he hopes to immerse the visitors. “It’s maybe not like an artwork, but it’s the art of the training of an AI, if that makes sense.”

I think the MoMA acquisition was a statement that said, ‘This is a field, and this is a medium, and this is in the collection’

The fact that Anadol didn’t immediately qualify this project as an artwork will surely be welcomed by art critics who have challenged his practice (though it will probably be scorned by just as many others who believe that, if it isn’t art, it shouldn’t be in the Serpentine). But discussions like these are nothing new. Last year, a debate blew up on social media when New York Magazine’s senior art critic, Jerry Saltz, expressed how he wasn’t a fan of Anadol’s work, shortly after the announcement that MoMA would be acquiring the artwork Unsupervised for its permanent collection – reportedly the museum’s first AI-generated work. Previously likened by Saltz to “a massive techno lava lamp”, the piece translates MoMA’s catalogue into a fluid, evolving image that stretches up to 24 feet tall.

Though it inadvertently thrust his practice under the art world’s microscope, the acquisition was a landmark moment that provided Anadol with validation. “I call this medium an AI data sculpture, AI data painting – relatively new introductions to the art forms,” he says. “And there was always this [noise], ‘No, it’s not art. Is it art?’ – classic debates that are important, but I think MoMA was a statement more like, ‘This is a field, and this is a medium, and this is in the collection.’”

The arguments made by Saltz and other critics are unlikely to go away entirely; if anything, greater exposure within esteemed institutions may well attract more sceptics as the man with a passion for big screens and even bigger datasets encroaches on the establishment – though it’s worth remembering that he was invited there in the first place.

It’s impossible to universally please art critics, who will likely forever debate whether his work is good art, or even art at all. But Anadol hopes that for every split opinion, he can unite a few more. “I’m trying to bring inspiration and hope in my work, and I really hope it can heal humanity – scientifically and spiritually.”

Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive by Refik Anadol is on show at the Serpentine Galleries in London until April 7; serpentinegalleries.org; refikanadol.com