How I Got Here: Nicholas Blechman

The New Yorker creative director talks about his first job in the industry and how to avoid predictability in editorial design

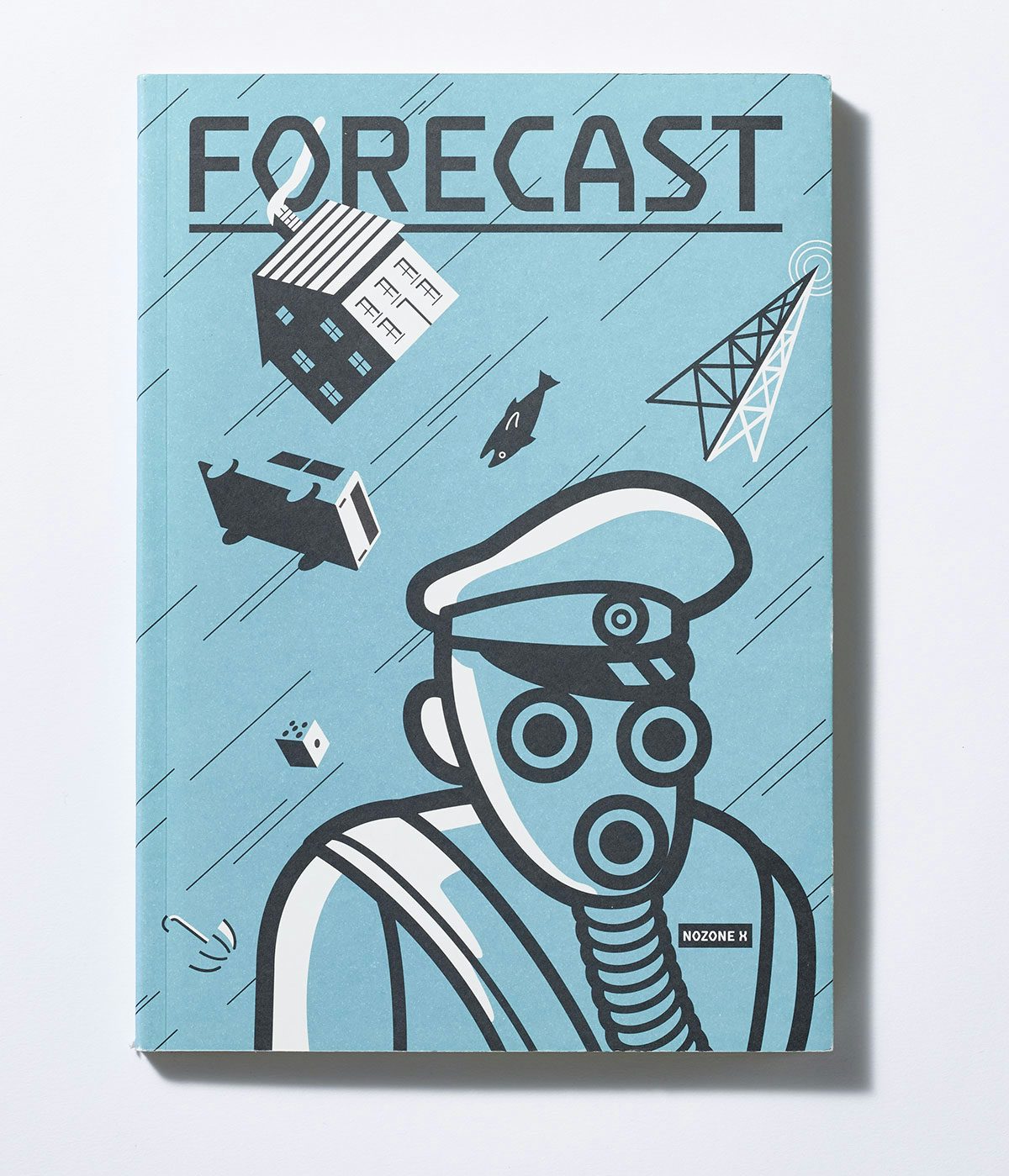

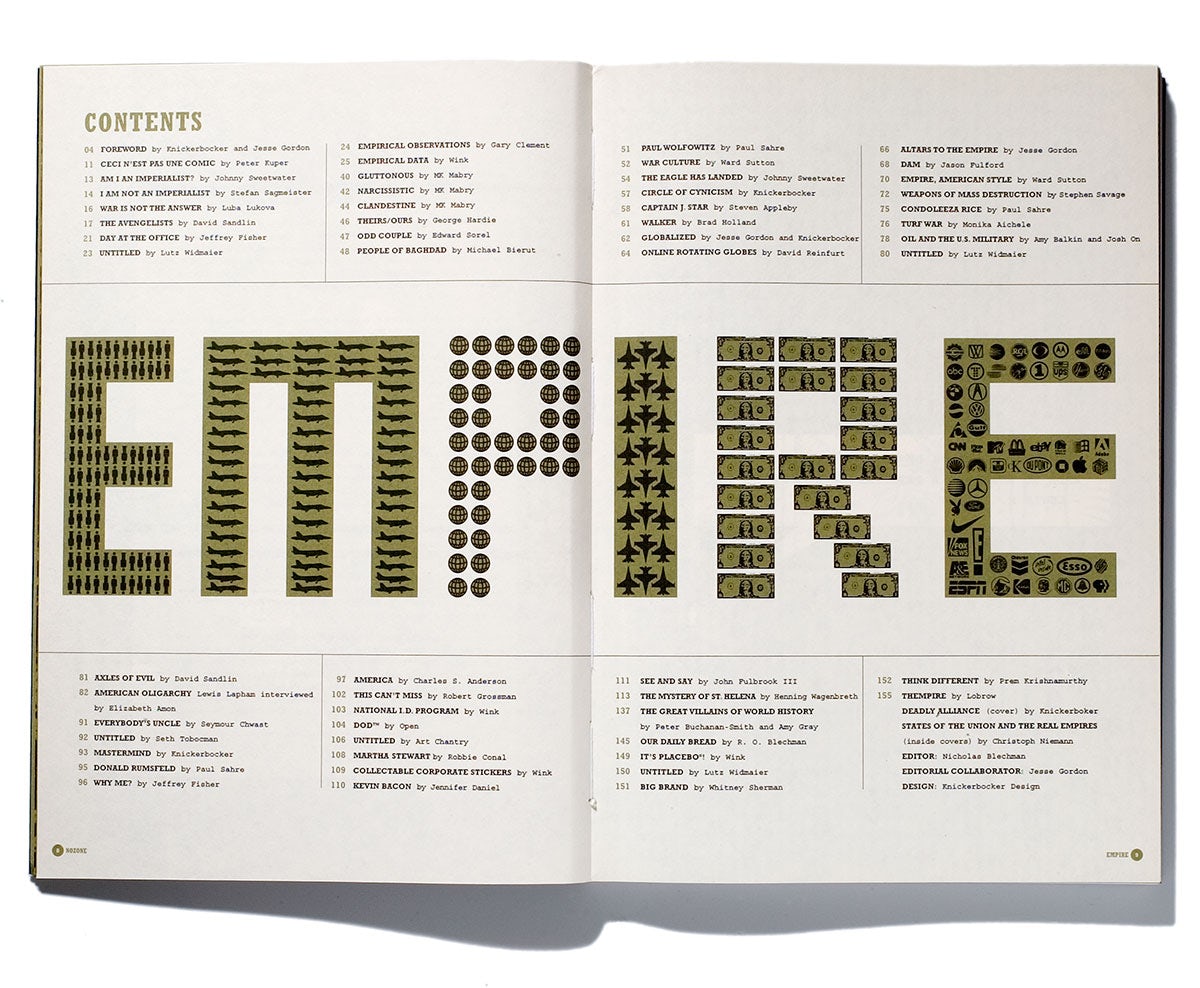

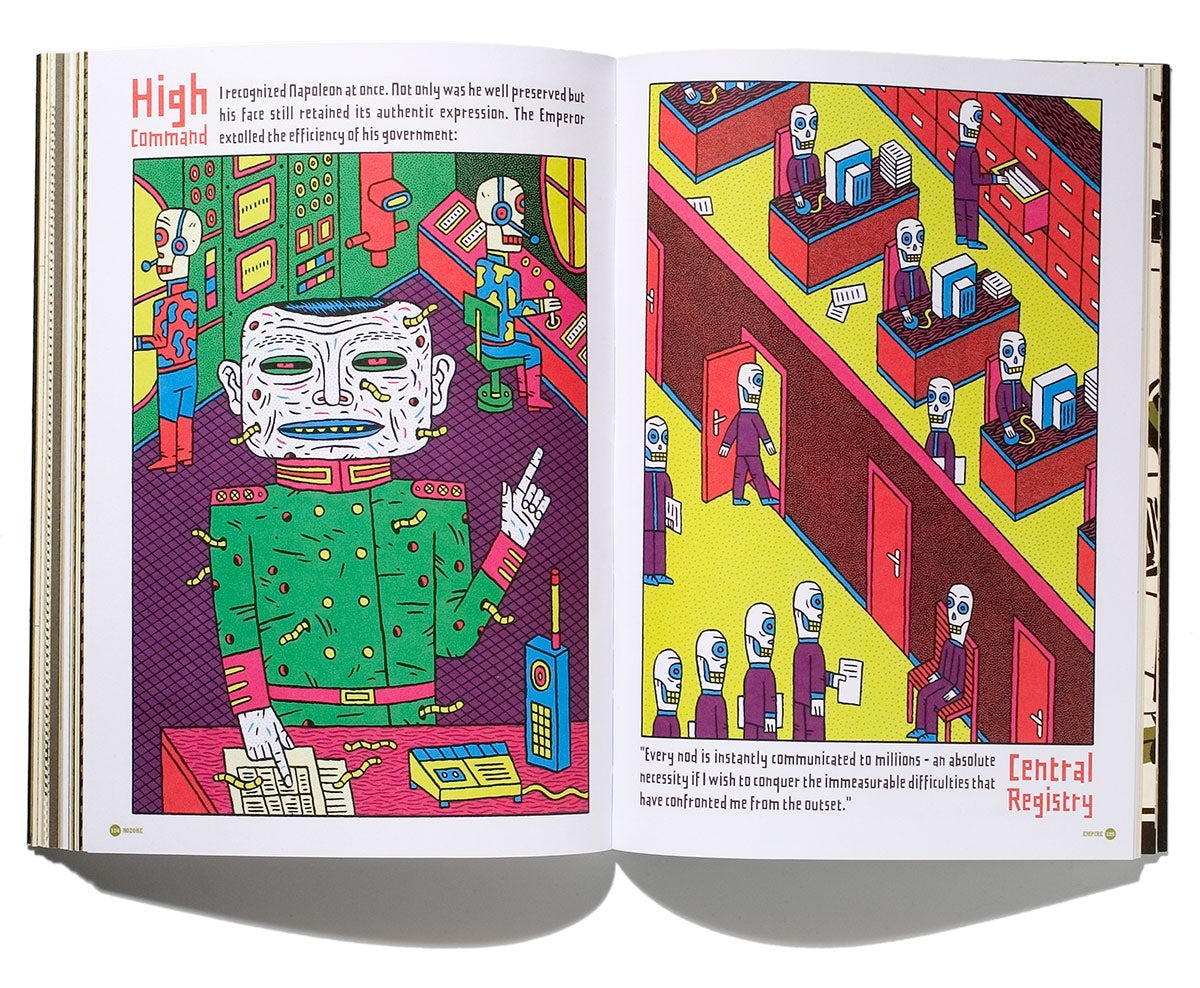

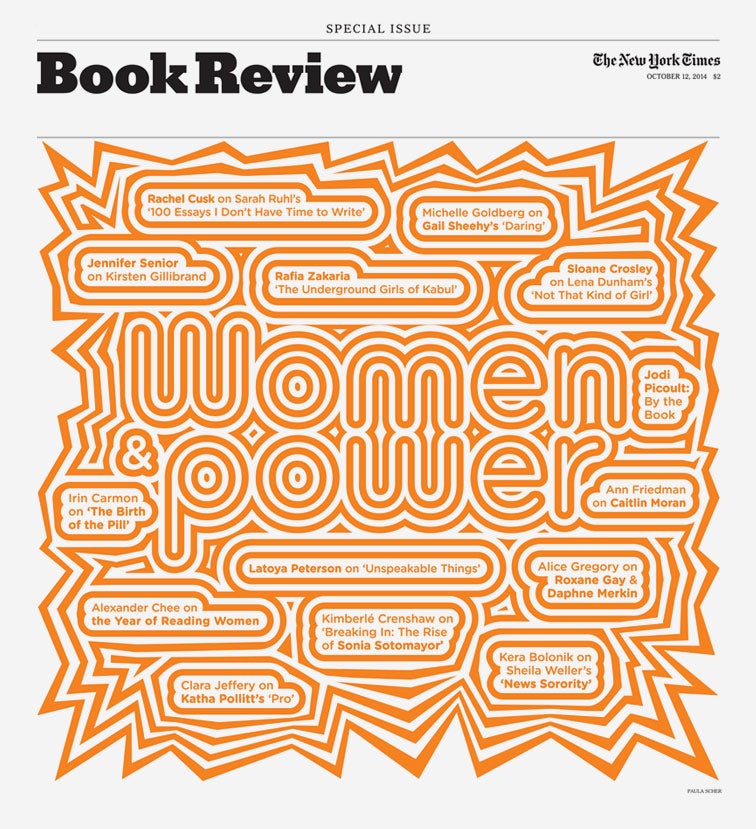

Designer and illustrator Nicholas Blechman has been creative director of the New Yorker since 2015. Before that he was previously the art director of the New York Times Book Review and The Times Op-Ed page. Since 1990, Blechman has also been publishing, editing and designing his political underground magazine, Nozone.

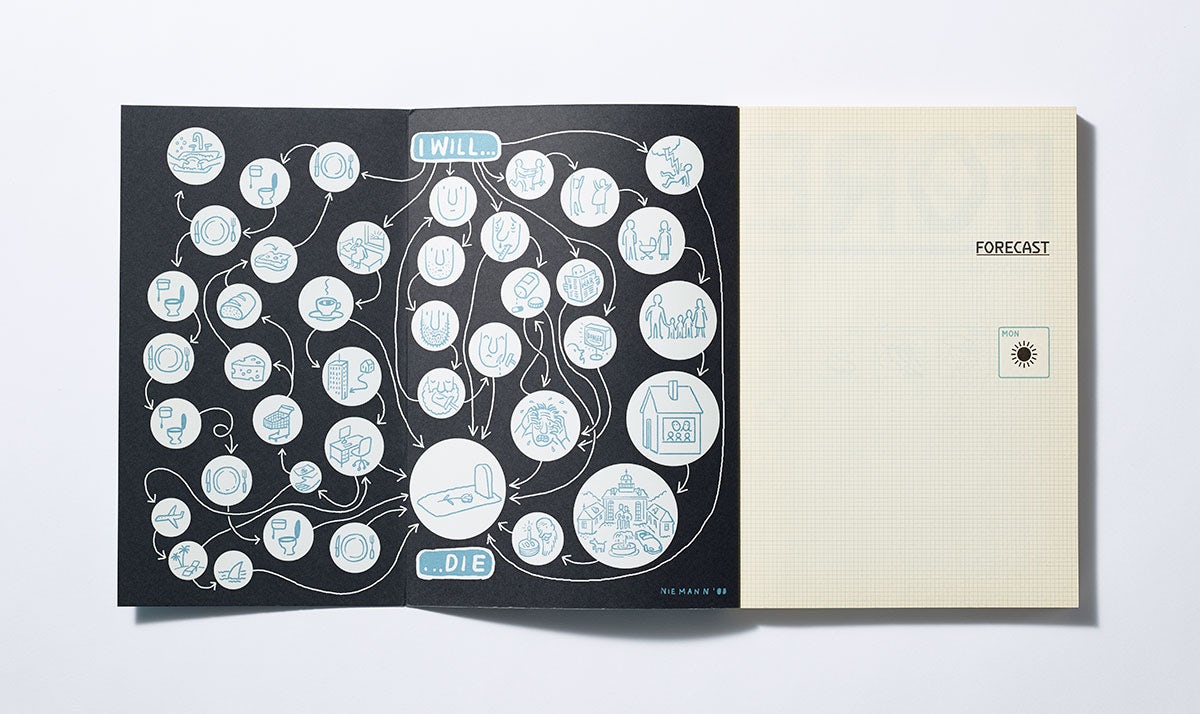

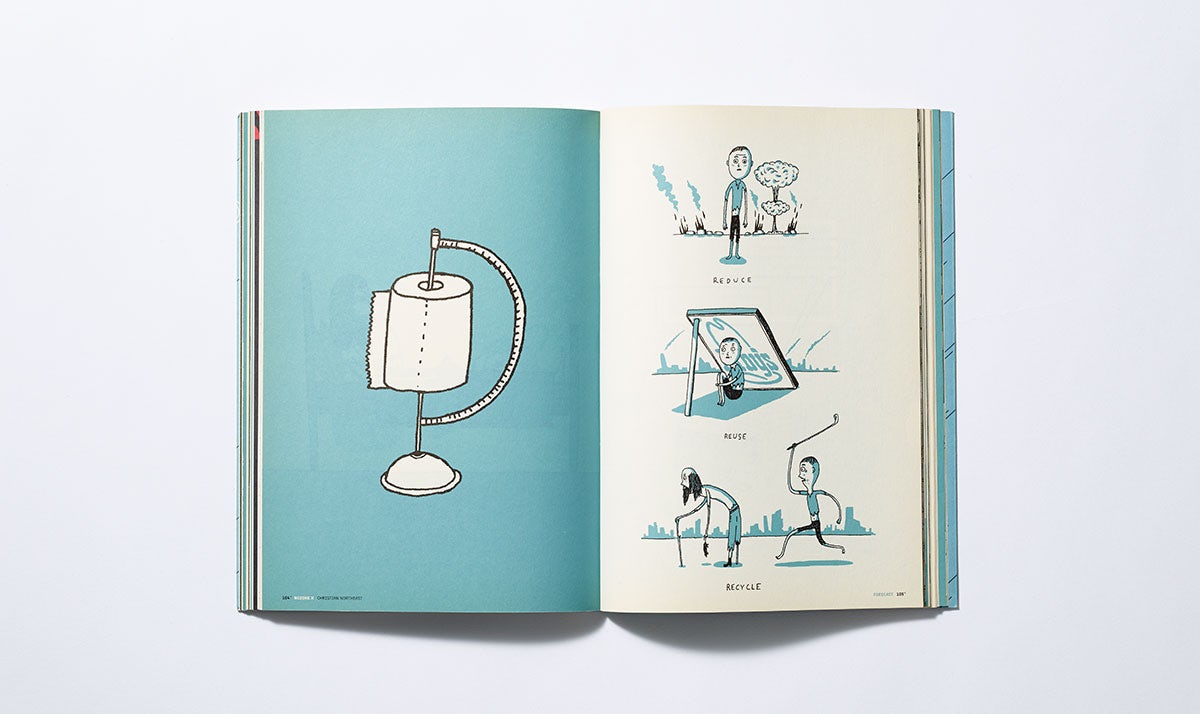

Blechman is known for his distinctive minimal style and this approach feeds into his illustration practice as well, which utilises clean linework and simple geometric shapes. His drawings have graced the pages of GQ, Travel + Leisure, Wired and the New York Times. He has also co-authored a number of books including a series of limited-edition illustrated tomes with Christoph Niemann titled One Hundred Percent.

Here, Blechman talks about his illustrator father, his first job in the industry, his day-to-day at the New Yorker and the challenges of editorial design.

On having creative parents I was surrounded by illustration and design. My father, R.O. Blechman, who is now 90, is an illustrator, and for many years ran an animation studio called The Ink Tank. He was friends with many of the legendary designers of his time, from Seymour Chwast to Bob Gill, and Maurice Sendak. Everyone passed through the studio.

He was very prolific, but paradoxically I never saw him draw. He did all his work at night, in a studio that looked like a gothic cathedral tucked in the Diamond District of Manhattan.

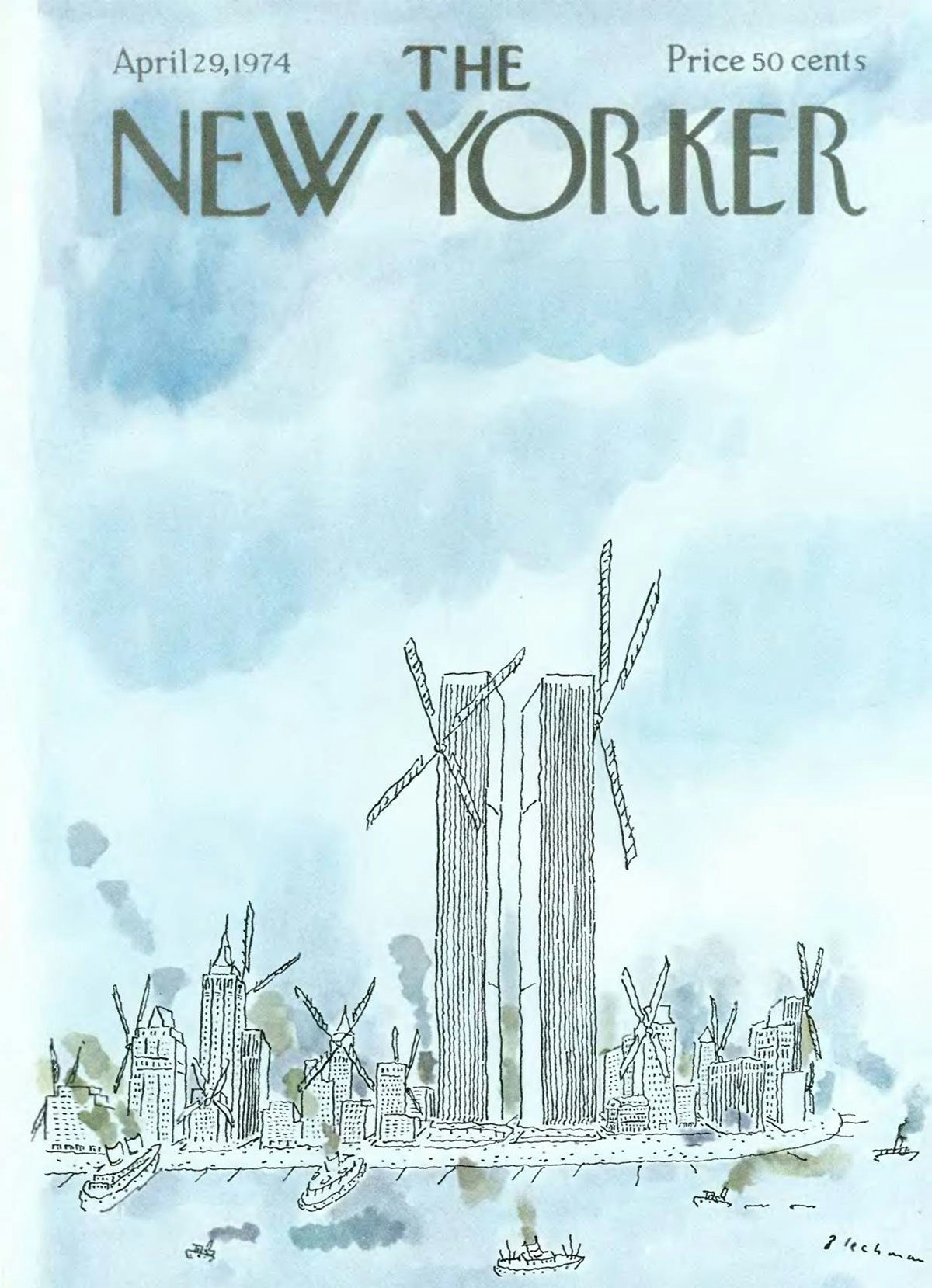

He never encouraged me to draw. Our apartment was filled with antiques rather than art. But I would occasionally see his work in the New York Times, or sometimes on the cover of the New Yorker, and I think this had a huge impact on me.

On finding art and illustration for himself I went to a rigid Napoleonic school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, the Lycée Français de New York. The only class I enjoyed was art. I doodled and drew through my classes instead of studying. It’s a miracle that I ever graduated from high school.

My father exposed me to the work of Sempé, Ed Sorel, Tibor Kalman, Paul Davis. He would bring home French comic books from his trips abroad, or introduce me to Colors, or Dance Ink. Raw magazine by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman had a massive influence. Not just because of the underground or obscure European illustrators they introduced, but also because of the innovative design, art direction, and impeccable printing.

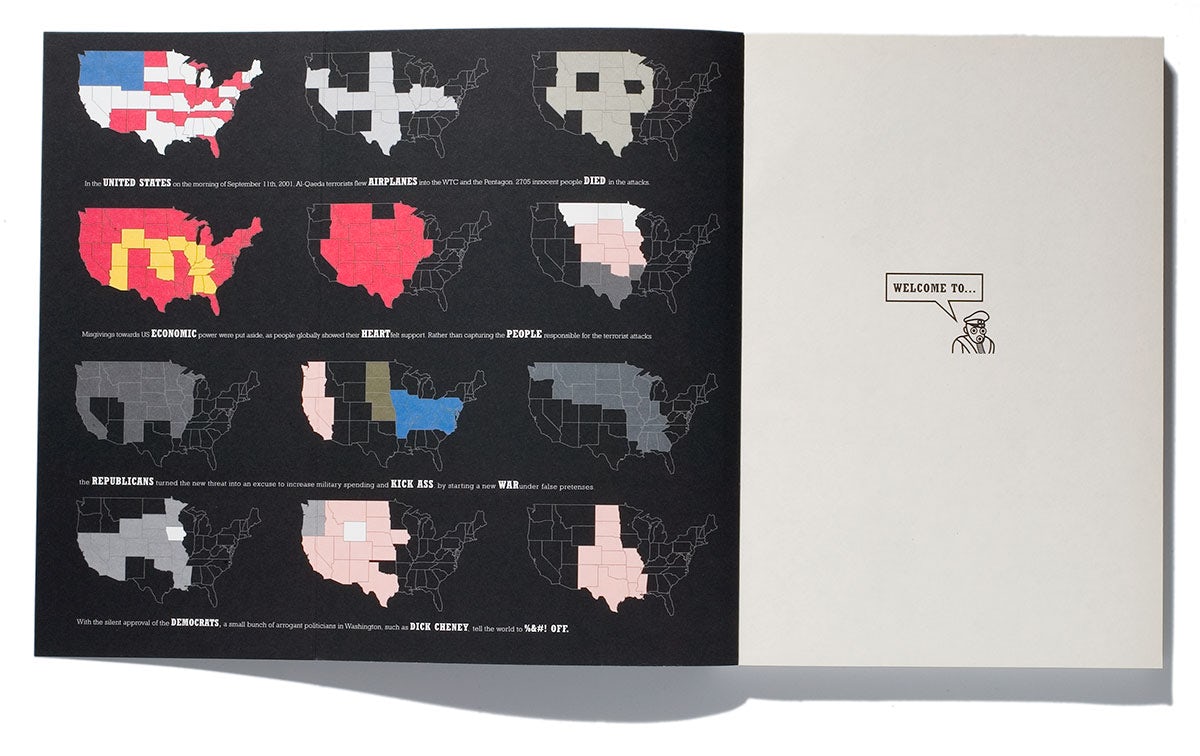

In the mid 80s, DIY zine culture was exploding. In college, I started publishing my own zine, Surge, followed a year later by Nozone. I assumed pen names to hide the fact that I was doing everything myself. I learned about printing, distribution, and began reaching out to other illustrators to solicit contributions. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was, in effect, art directing.

On his university years I went to Oberlin College in Ohio, my father’s alma mater. I majored in art history and studio art. For four years, I split my time between the library, or the art studio. I discovered silkscreen printing, and began drawing on a Mac. The most valuable lesson, perhaps, was discipline, and the importance of work. I was a boringly serious student.

First job in the industry Immediately out of school, I interned at Paul Davis’ studio. Paul was art directing and designing a magazine called Wig Wag, which was aspiring to be a hip version of the New Yorker. To my disappointment, I was not allowed to touch the layouts or influence the design. I mostly operated the stat camera, sometimes falling asleep in the dark room, or I would be charged with taking their dog out for walks. But the experience did expose me to how a magazine is put together, and gave me the opportunity to meet illustrators like Brian Cronin and Gary Baseman.

On enjoying editorial design I always gravitated towards illustration or design in the service of communication. The Op-Ed page of the New York Times was rich in visual ideas, and every day I would open the paper to see work charged with political meaning. I fell in love with illustration that had a message, or a clear idea, and editorial design was the context in which these drawings lived.

On becoming an art director at the New York Times Strangely, I never went to graduate school for design. Instead, every year I would publish another issue of Nozone, while working at my father’s animation studio. One day, Steven Heller, the venerable art director at the New York Times, asked if I would be interested in designing the op-ed page for a week while the art director was out of the office. Without hesitating, I accepted, and after a year, I was hired.

Working at the New York Times It was unlike anything I had previously experienced. The relentless rush of deadlines, the daunting sense of shaping public opinion in a paper seen by hundreds of thousands, the intimidating approval process with executive editors, the freedom to assign an article to any illustrator I chose….

In the end I was there for more than ten years. I started at the Op-Ed section, then after four years left to create my own studio, Knickerbocker Design, in a space I shared with Christoph Niemann in Chinatown. I then returned to The Times in 2005 for another ten years, first as art director for the Week in Review section (now Sunday Opinion), and then as art director for the Book Review. I have vivid memories of sneaking into the press rooms late at night, three floors below street level, and watching massive web presses churn out the newspaper at terrifying speed. It was like a scene out of Citizen Kane.

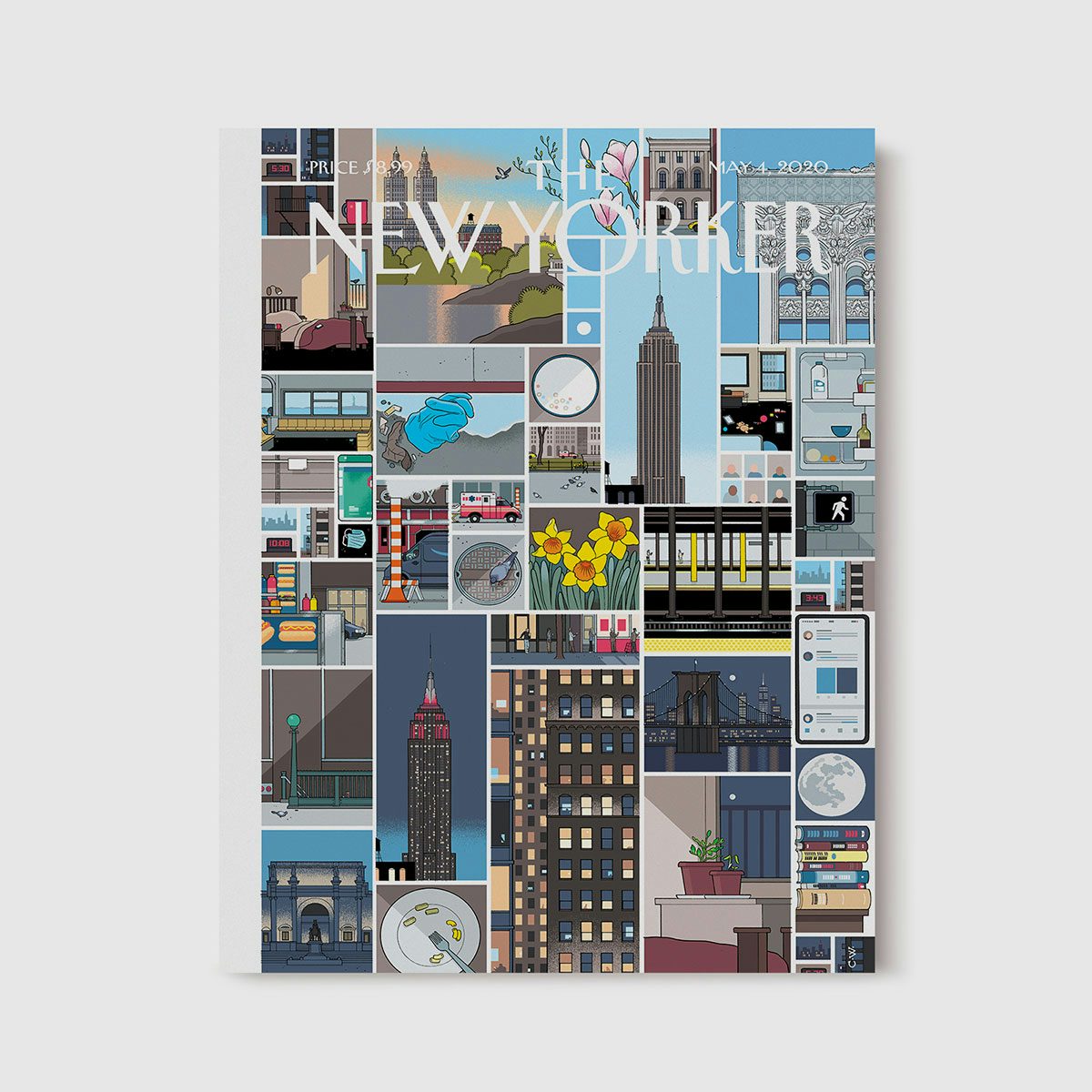

Why working at the New Yorker was the next goal The only other place I ever wanted to work was the New Yorker. I grew up with the magazine, and I have a vivid memory of seeing a cover of my father’s when I was seven. It was a drawing of Manhattan covered with windmills, published during the energy crisis of 1974.

The New Yorker has a strong legacy of illustration and is the gold standard for any aspiring illustrator, including myself. Beyond art, I’ve always loved the writing that’s at the heart of the magazine, from Calvin Tomkins to Jill Lepore, and so many more.

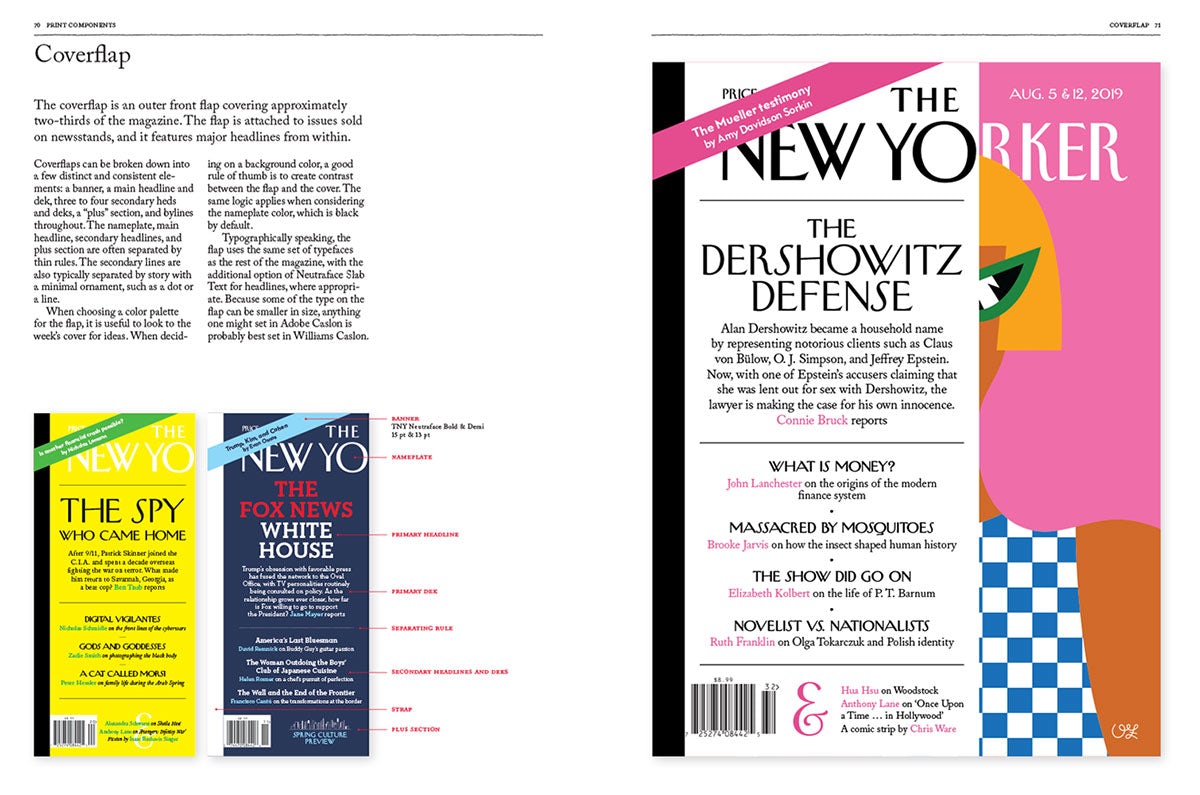

In the role of creative director, I’d have the opportunity to shape not only the visual style of the magazine, but every platform and product associated with it, from a coffee mug to the New Yorker Festival. To this end, we created a style guide, to help define the visual ecosystem of the magazine.

New Yorker Festival film. Illustration and animation by Buck

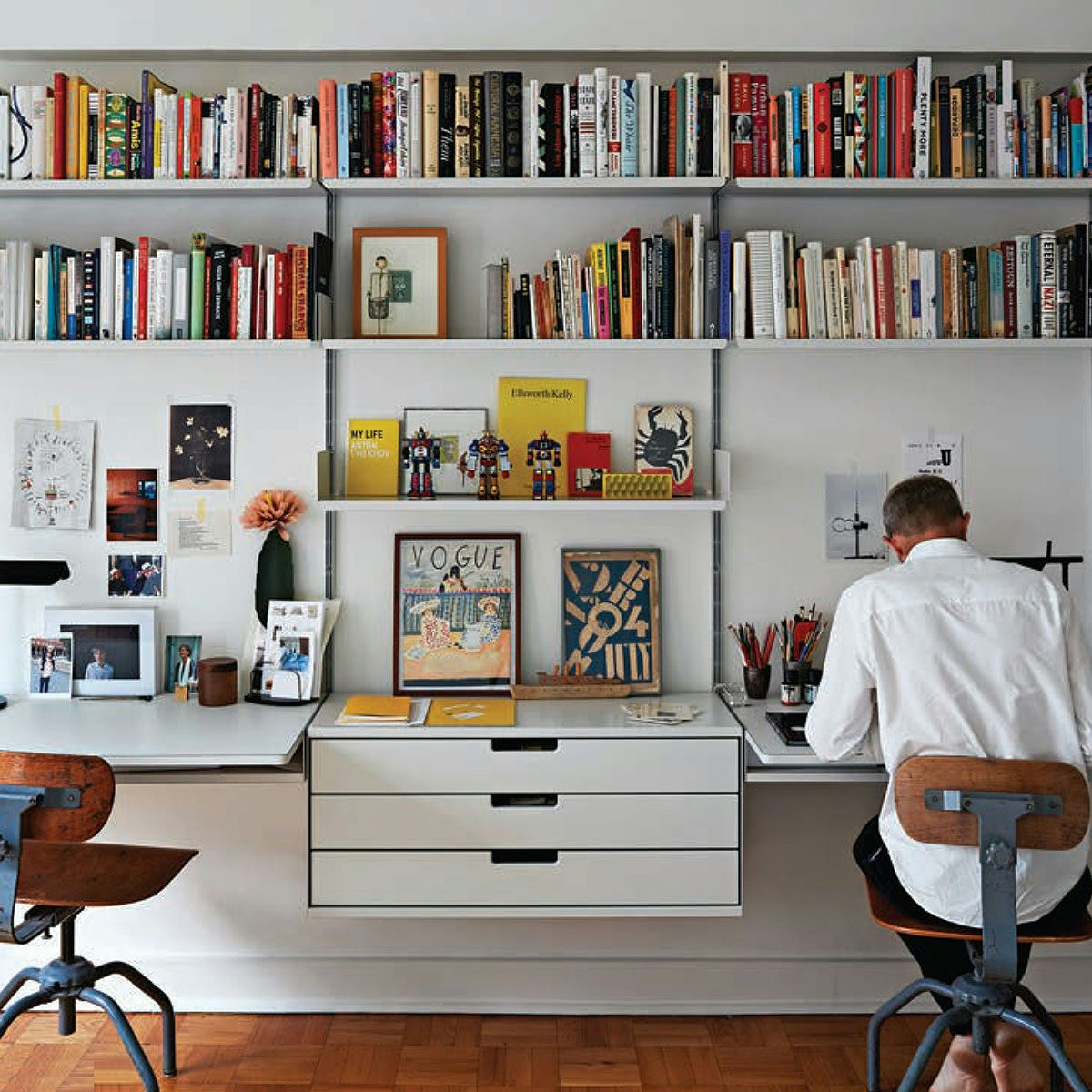

Day to day at the magazine My routine has been upended by the pandemic and working remotely, but it always begins with a strong cup of coffee at 6am. I try to tackle one personal project (an illustration or a series of drawings) before the breakfast rush and the scramble to get the kids to school, arguably the most challenging moment of my day. By 10am, I check in with the art department to chat with the team, look at sketches for spot illustrations, and discuss upcoming assignments.

The rest of the day is consumed by Zoom meetings, reading manuscripts, and general management issues. I am usually juggling two to three special projects simultaneously, such as planning the identity for the New Yorker Festival, or figuring out how best to package a story both in print and online, or come up with a new product for the New Yorker Store. The challenge is to keep these multiple projects moving forward, and make sure they are up to the highest standards of design.

After a few Zoom meetings in the afternoon to check in with the digital design teams, I catch up on my email. By 5:30pm family life begins to intrude, and I have to dash out to take my son to soccer practice or start boiling water for pasta. Before the pandemic, I’d typically end the evening at Long Island Bar, with Matt Willey or Christoph Niemann.

New Yorker Festival film. Illustration by Christoph Niemann with animation by Nicolo Bianchino

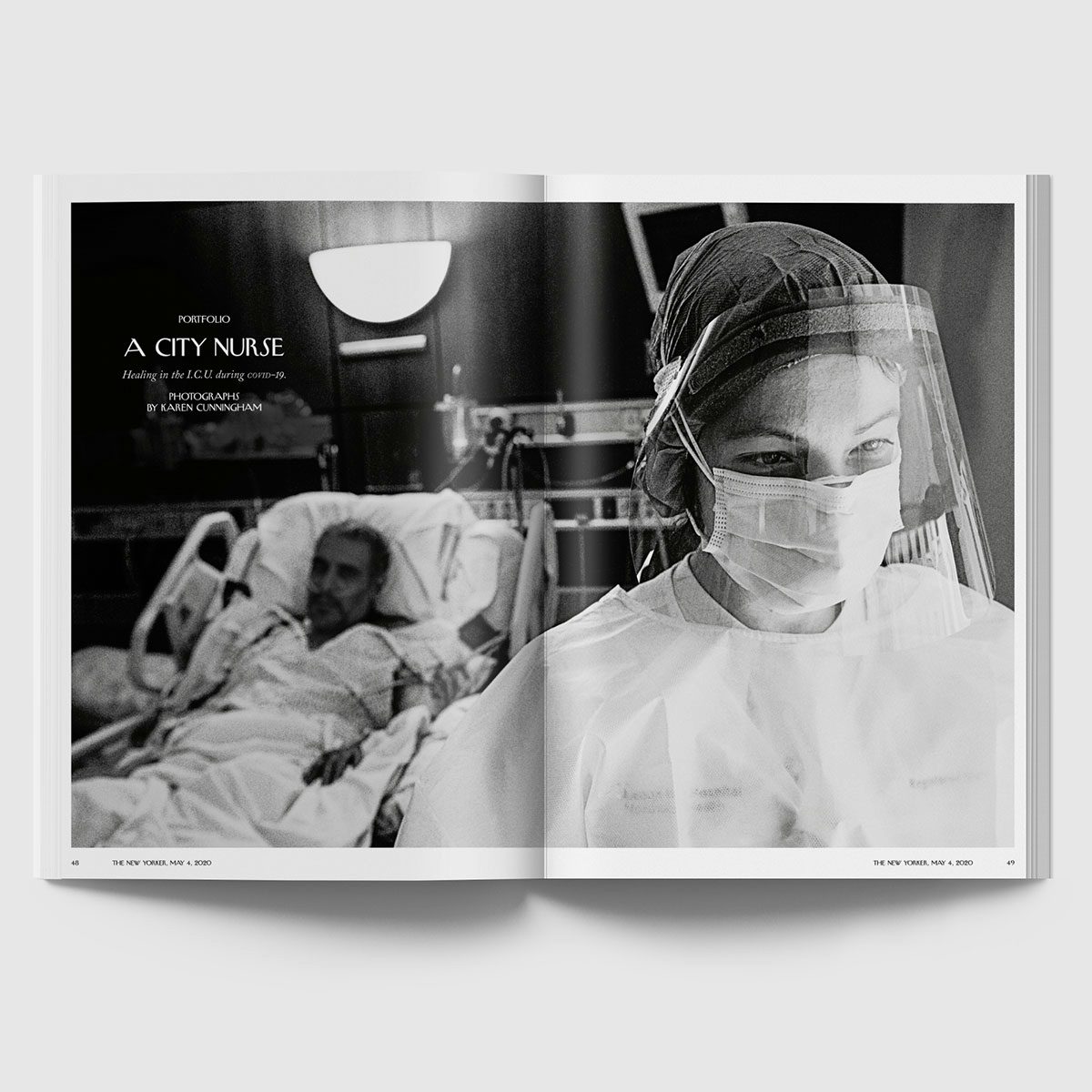

On the team who makes it all happen I work most closely with the five designers on my team, starting with the design director, Aviva Michaelov. She is constantly problem solving through design, asking the big strategy and brand questions but also focusing on the details of the weekly magazine. Photography plays an essential role in the New Yorker, and I’m fortunate to work with Joanna Milter, our director of photography, who is constantly surprising me with the extraordinary work she commissions. (The covers and cartoons are outside of my jurisdiction.)

I regularly show art to David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker. Before the pandemic, he would stroll through the art department to see how the issue was coming along. Now I send sketches and layouts via email, getting approvals, feedback and, yes, rejections. I love the back and forth with editors. I think it is an essential part of the process, and often leads to better art in the end.

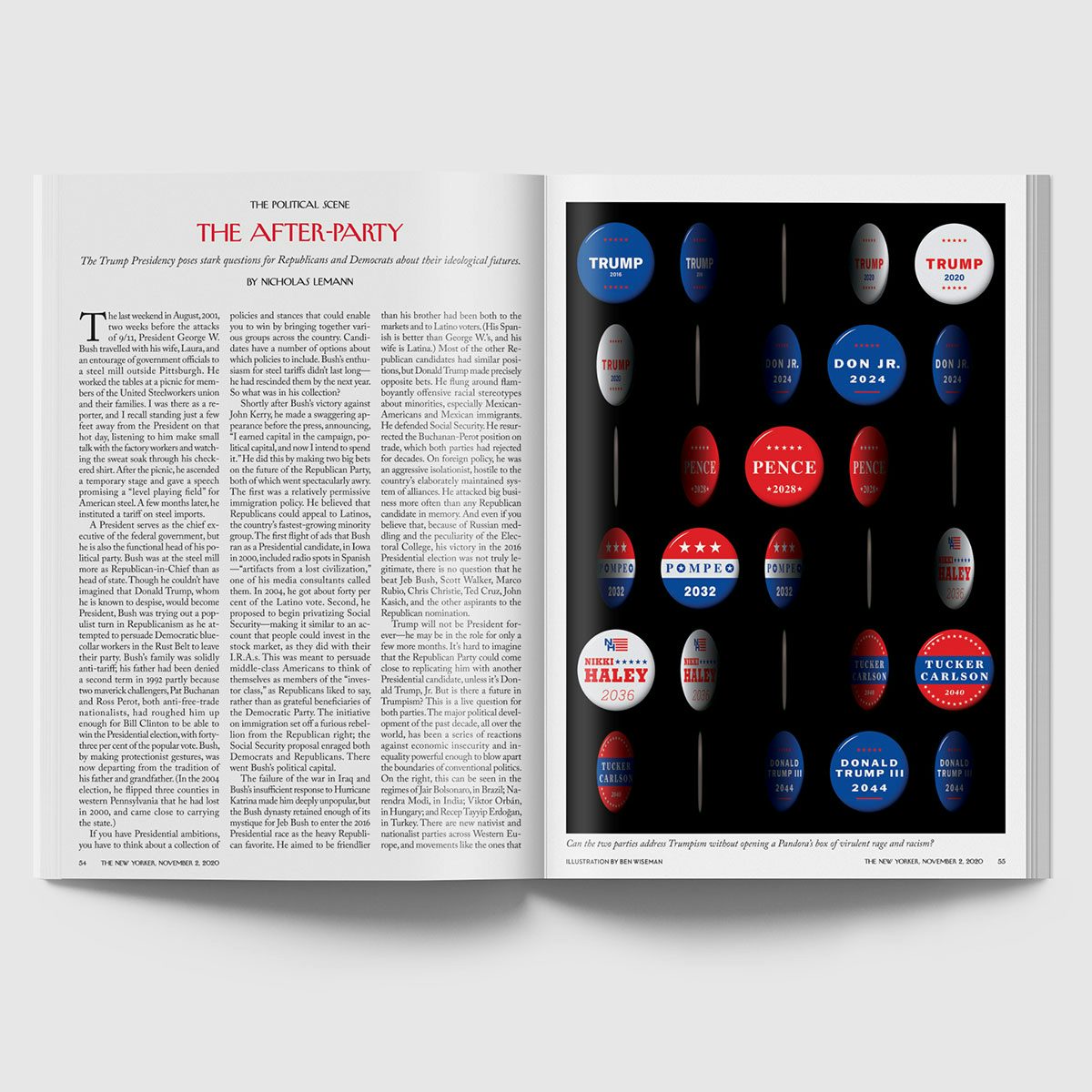

The challenges of editorial design The last minute switching of stories or moving of pieces from one section to another, while keeping up with the ever-changing news cycle, are among the challenges. And, quite frankly, trying to keep an almost century-old magazine looking fresh each week!

I think it is very easy to become complacent, and to fall into a pattern of predictability by getting caught up in the grind of deadlines. I try to approach each article, each project, from a fresh perspective. It’s important to push yourself to think not just journalistically but also creatively. Though ‘taking risks’ has become a cliché, for me it means discovering new designers or photographers, and thinking about visual solutions that don’t mimic the text but go beyond it, by adding another layer of meaning.

Incorporating illustration into his practice Being an illustrator makes me a better art director, and vice versa. If I didn’t pursue my own drawing, I’d go crazy. Drawing is a form of therapy. I think of my illustration style as minimal and idea-driven. Though recently I’ve been indulging in non-conceptual solutions. I’ve been rediscovering a childhood influence, the pen and ink work of the French illustrator Folon.

Advice for those starting out Don’t wait for the work to come to you, jump-start your career by self-publishing or self-authoring your own projects. Immerse yourself in design, and promote yourself relentlessly.