Inside the V&A’s show celebrating disabled design and culture

Design and Disability at the V&A is full of projects variously useful, beautiful, or just amusing, celebrating the long-running contribution of disabled people to design

As you’re reading Creative Review, you’re likely to be of the mindset that design is meant to make things better. Of course there are exceptions to the rule – things designed intentionally in the service of hate, violence, or misinformation – while your belief may also have been shaken by awareness of your now-absent attention span, thanks to devices and apps designed a bit too well.

But have you heard of a Disability Dongle? It’s a term, coined by Liz Jackson, founding member of disability-led critical design collective The Disabled List, to describe well-meaning but ill-conceived design efforts, which take an existing product and try to improve it in some way – it might be adding new tech (now most likely AI, as current hype and funding dictates) – but end up making it worse.

“The white cane is often the most toyed around with by non-disabled designers,” says Natalie Kane, curator of the V&A’s new exhibition Design and Disability, which focuses on the contributions of disabled, deaf and neurodivergent people to design and culture. “Non-disabled designers try to add loads of bells and whistles to it, like GPS, AI, other layers and signals of information,” says Kane, “because they think it’s helping to ‘fix’ or ‘solve’ disability, but actually people just need something really simple.”

This isn’t to say the V&A’s exhibition is anti-innovation: the white cane on display is not the original design, but a 1950s folding version, made in response to a woman’s need to fold the cane into a bag while shopping. Instead, the exhibition celebrates disability-first practices of innovation – showing that rather than being passive recipients of design (and those sometimes expensive, undesirable ‘solutions’), disabled people have a rich design culture of innovation and making themselves.

For those techno-utopians, there is much that is transformative among the exhibition’s 170 objects dating from the 1940s to the present. Yet while they may go on to become mainstream, many of the designs were born of an individual’s need or developed through unique and often community-led hacking cultures.

For hundreds of years, and even now, disabled people were institutionalised and denied the chance to live independently – and this extends to the choice not to live saintly, perfect lives

For example, the Touchstream keyboard was made by software engineer Wayne Westerman when struggling to use a standard keyboard due to hand pain; it was later sold to Apple to be integrated into the iPhone 1. But, as Kane cautions, what enables one group of people can also disable another, such as in the dangerous and toxic mining practices behind such modern tech.

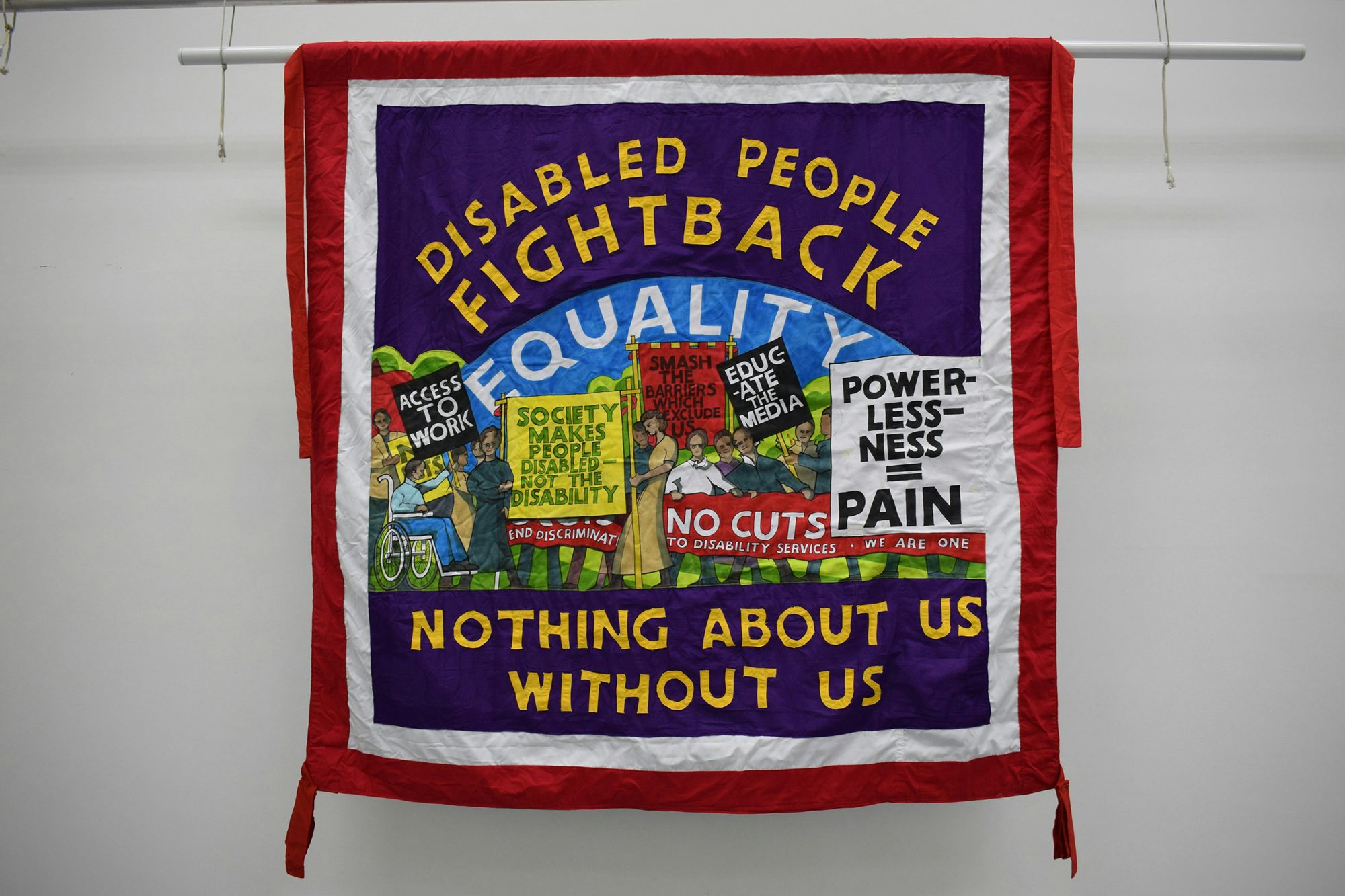

While the exhibition wants to centre joy, it contains a strong strand of activism, acknowledging injustices past and present. There are graphic slogan T-shirts reading ‘Piss on Pity’ from Sue Elsegood and DAN (Disabled People’s Direct-Action Network), and a poster by AIDS Ahead which reads ‘The best lovers are good with their hands’, while hands photographed signing in BSL spell out ‘Use a condom’. Tongue-in-cheek it might be, but it sought to compensate for the failure of GPs to communicate the dangers of HIV to deaf patients, Kane explains.

Ideas of what is and isn’t relevant to a good life crop up repeatedly: Cindy Wack Garni developed a series of simple prosthetics for her to apply her eyeliner, or effectively cut up her steak – things for which her expensive robotic hand had never been developed, and medical professionals close to her deemed “not a priority”.

Consider too the fact that most blind people rely on others to vote. A McGonagle Reader is on show here, a device from 2022 which allows blind, partially-sighted, or people who cannot read English to vote independently, but many councils still fail to take it up. The Signstrokes project, by Chris Laing and Adolfs Kristapons, creates a new linguistic framework for an absence of specialist architectural terminology, highlighting the stark lack of representation in the industry.

Bells and whistles are much encouraged too, when they’re the point. There is a glistening carnival costume by Maya Scarlette, a designer with the limb difference condition ectrodactyly, which references Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, as well as fashion for dressing ‘well’ rather than simply being accessible. Other exhibits include the Woojer Vest for deaf raves, which translates audio into vibrations just as immersive, and an accessible, gender-free sex toy called Enby 2 by Wild Flower.

Wall text notes that “for hundreds of years, and even now, disabled people were institutionalised and denied the chance to live independently” – and this extends to the choice not to live saintly, perfect lives. In response to the tendency of ads to frame Paralympians as superhumans, yet focus on their impairments rather than skill and ability, performance and video artist Katherine Araniello presents Meet the Superhuman, where she smokes, eats junk food and drinks champagne in Olympics-branded sweatbands.

The occasional focus group is not enough to ensure that disabled talent is employed and sustained … and is able to be part of the design industry

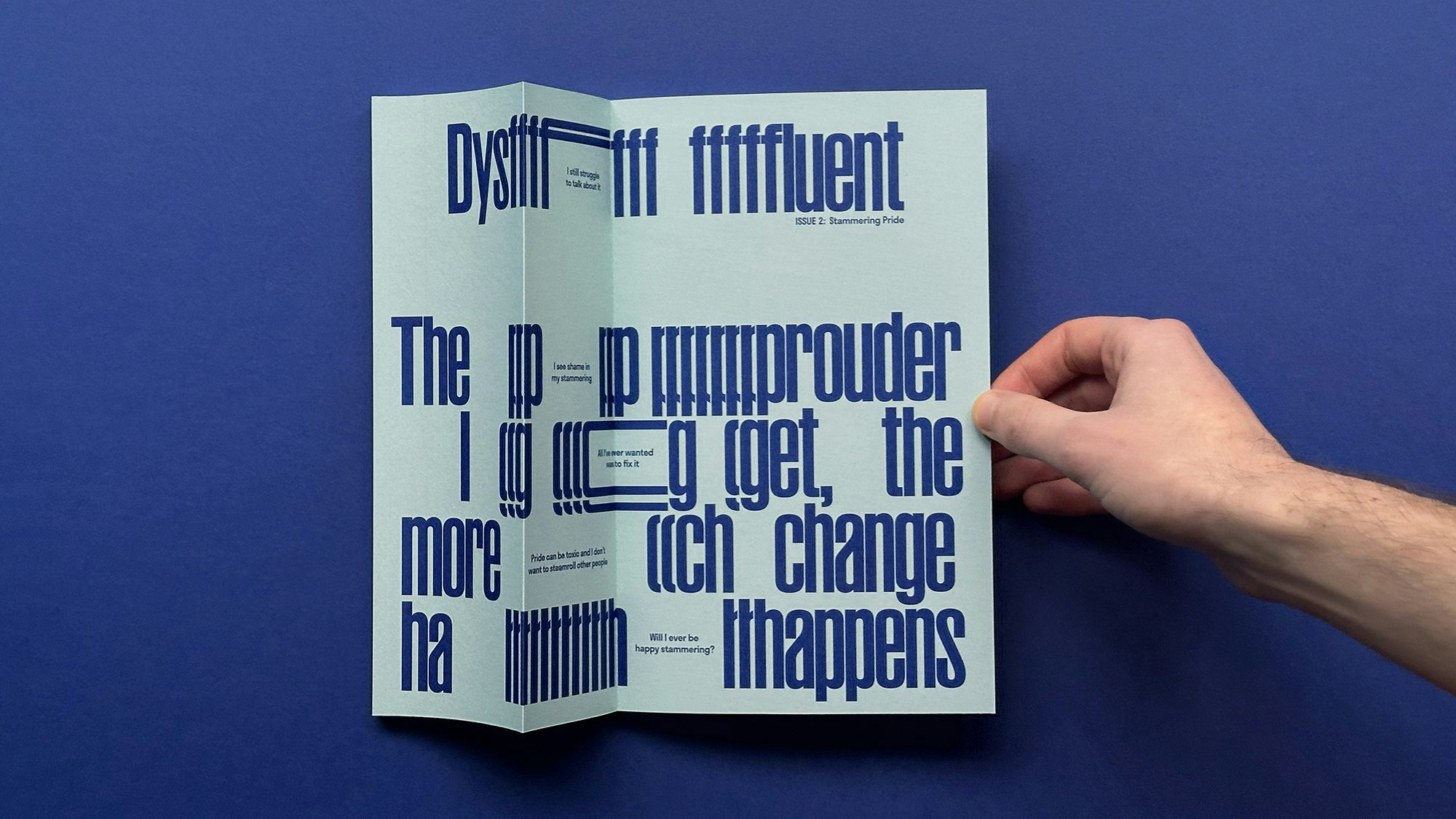

For any visitor, disabled or non-disabled, designer or not, the exhibition offers a bounty of ideas on how to live – shaped by disabled experience, not in spite of it. You might find yourself drawn to Dysfluent magazine by Conor Foran, whose graphic devices are informed by his stutter, or to playing Unpacking, a calming game by Witchbeam where you slowly unpack items from boxes, accompanied by a gently bouncing soundtrack.

Harry Leeming’s app Visible offers prompts for physical activity – but rather than urging users to move harder and faster, it teaches them to sustain energy instead, designed for people with energy-limiting conditions from chronic fatigue syndrome to long Covid.

Created through workshops with advisory groups, the exhibition was the result of many voices, explains Kane, not always aligned, but resulting in “generative conflict”. This also applied to the exhibition design, by the V&A Design Studio with support from The DisOrdinary Architecture Project. A welcoming palette of colour and material balances requirements for low vision and neurodiversity, and the use of reflective surfaces is informed by DeafSpace principles, while pleasingly tactile patterns on the side of display cases demarcates the exhibition’s sections. Ample seating throughout provides rest for those who need it, but also encourages people to take time to sit together, rather than moving through at speed.

It’s a reminder that points of difference, if worked with or given space, are additive. There is a plan to incorporate some of the exhibition’s innovations into wider museum policy going forward, subject to audience feedback, says Kane. There are thriving disabled cultures already, but for the design industry more widely, there is an opportunity to challenge its ableism – “the occasional focus group is not enough” – she adds, to “ensure that disabled talent is employed and sustained … and is able to be part of the design industry.”

Design and Disability is on show at the V&A South Kensington in London until February 15; vam.ac.uk