How wayfinding could make us happier and healthier

Signage plays a critical practical role in the public realm, but is it living up to its creative potential? We discuss how wayfinding can establish a more joyful and emotional connection with the world

“It’s well beyond ‘toilets are over there’,” jokes Wesley Meyer, creative director at F.R.A Creative, which specialises in wayfinding and placemaking for the public realm. “Now, we’ve got to craft the experience.” We’re in the middle of a conversation about signage which has spanned everything from the dire state of hospital wayfinding – ironically, something Meyer experienced repeatedly as a teenager, and that almost certainly influenced his interest in the discipline – to the studio’s decision to embed a human tooth in a sign at London’s Borough Yards development.

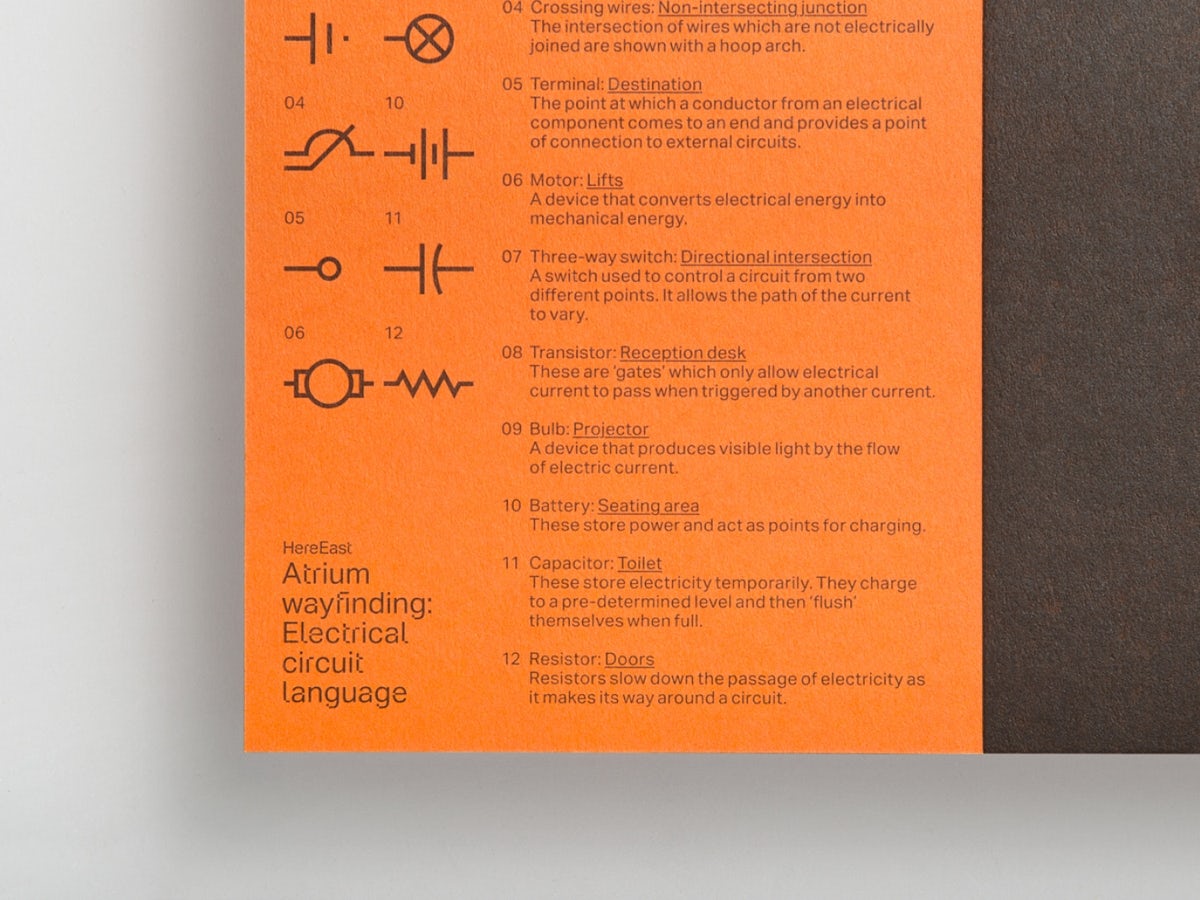

“We’ve stopped trying to solve the problem of, are people lost?,” he explains. “Or, are they getting from a to b? We are still doing that, but I think it’s almost too easy. The higher challenge is, are people bored? And how do you reward people for spending time in a place, especially repeatedly? There’s a big difference between when you first go to a place and it’s like, ‘Where are the lifts? Where are the toilets? Where are the shops?’ After that, everyone knows where they’re going and stops looking at signs. How do we reward these people that do come back?”

Alan Stevenson, wayfinding strategist at design studio Dnco, agrees. “Wayfinding can help to develop a sense of place,” he tells CR. “You can set boundaries, emphasise entry and exit points, and materials and typography all have a voice. By putting them together carefully, you can really emphasise that sense of place. You get a lot of visual impact and bang for your buck compared to other architectural interventions.”

Meyer believes expectations for wayfinding are higher for both clients and the public, saying that businesses are keen to encourage people to stay longer, and reward them for investing time in a place, while people are looking for experiences and memories they can share. F.R.A responded to all this with its work for south London retail development Borough Yards, by incorporating more playful kinds of wayfinding such as huge neon signage and four-storey tall murals, alongside bits of design that might only become obvious over time.

“In a year they’ll start finding the little teeny tiny things that we hid in the environment,” laughs Meyer. “It gives you a chance to say, ‘Oh, I walked past this seat 100 times on my way to work, and never noticed someone embedded a 17th century coin and a human tooth in the mortar over there, and put a little plaque to explain why they’re there.”

It’s a bit like a relay race, where one side hands you onto the next side and gets you to your destination

That playfulness doesn’t mean wayfinding doesn’t have to work hard, however. According to Stevenson it’s a balancing act, and people have to first trust and understand the signage before it can have fun. He believes designers can use landmarks to help push the boundaries, using large scale graphics or sculptural elements to help guide people. “That’s the place to be more expressive, and the backbone of wayfinding,” he explains. “Wayfinding shouldn’t be dull, but it’s more important that you get the flow of information – it’s a bit like a relay race, where one side hands you onto the next side and gets you to your destination.”

There’s also the long term to think about, with the discipline differing from many other graphic arts just in terms of its permanence; signage could potentially stay up for decades at a time. That means designers often have to lean into classic gestures, without being so boring or conservative as to become invisible. Sometimes it’s about subtle interventions, such as F.R.A’s work in Dublin’s Trinity Library – where the studio examined the hand-written signs of the book stacks, and created a signage typeface that echoed their wonky letters.

Meyer even believes wayfinding can impact people’s wellbeing – and he mentions his experience taking his mum to hospital appointments as a teenager as a clear example of when it can go wrong. “You’ve got sick people, worried family members, overworked staff, vendors, and so many people using these buildings, and the buildings themselves just fight you,” he says. “They don’t want to be orderly.”

In contrast, if wayfinding can be understandable and engaging enough to earn people’s interest and trust, then it can potentially encourage them to explore new routes, or walk instead of catching public transport, and reward them along the way with some kind of graphic intervention. Robin Howie, founder and creative director of design studio Fieldwork Facility, believes wayfinding can have a huge, positive impact on people. He says there’s enormous potential for more of it, as signage moves away from a draconian, ‘no ball games’ philosophy.

“I think in terms of signage being in the public realm, it’s participating in that place, and it would be really interesting to make destinations feel more joyfully within reach – rather than just scientifically or logistically how you get there,” he tells CR. It’s something Fieldwork Facility did with its bright yellow, bendy signage for Brent Cross town – designed to draw out some of the area’s personality, rather than being dry and formulaic. “The brief was essentially, can you move people from a to b, but put a little pep in their step at the same time?” says Howie. “Can you make them want to be a little more reactive, or move them in a little bit more of a playful way?

“Why wouldn’t you want more signage which is joyful and playful? You don’t want all signage to look like you’re living in Willy Wonka land, which would be too much, but on the other hand, projects that are full of the joy of a city should feel optimistic, and playful and invite participation in the city … I also think it’s a different thing, for something to look playful and feel playable.

“Playable is more of a behaviour trait, and it would be really easy for us to see more playful design, but it’s more about how it makes you feel, act and behave. I’m thinking about more gamification – how do you get people to feel like going ten minutes further down the road is an interesting prospect, rather than conveniently going to your left or right? How do you make the place which is a little bit further feel a) attainable and b) a really interesting prospect?”

As far as Howie is concerned, creating a more positive public realm isn’t down to signage alone. He says traditional wayfinding needs to work in partnership with a broader kind of creativity that improves the world around us. For example, Fieldwork Facility installing brainteasers under London’s Hammersmith Flyover, or creating ‘rewilding rave’ posters to support biodiversity in the area. F.R.A has also explored more unconventional forms of ‘wayfinding’, via concepts for hiding a full symphony orchestra behind a hoarding, or placing movie props in building sites for people to peer in at. “How nice if someone breaks routine and expresses curiosity – it’s a scarce resource, so [we should] give them something for it,” says Meyer.

“Why are there so many bland and overlooked parts of the public realm?” agrees Howie. “It’s not a case of everything being all-singing and dancing, but why don’t they have their inherent identity, and speak to the community and have an active place? Specifically the underpasses, and vacant spaces, and bricked up walls. Graphic designers fetishise over ghost signs, and advertising is a force in the public realm, but isn’t it important to have things which aren’t selling to you, and are contributing to a collective whole?”