How I Got Here: David Gentleman

As David Gentleman publishes a new book on London, to coincide with his 90th birthday, we spoke with the artist about his lengthy career and the stories behind his work, including his Penguin book covers and platform-length Underground mural

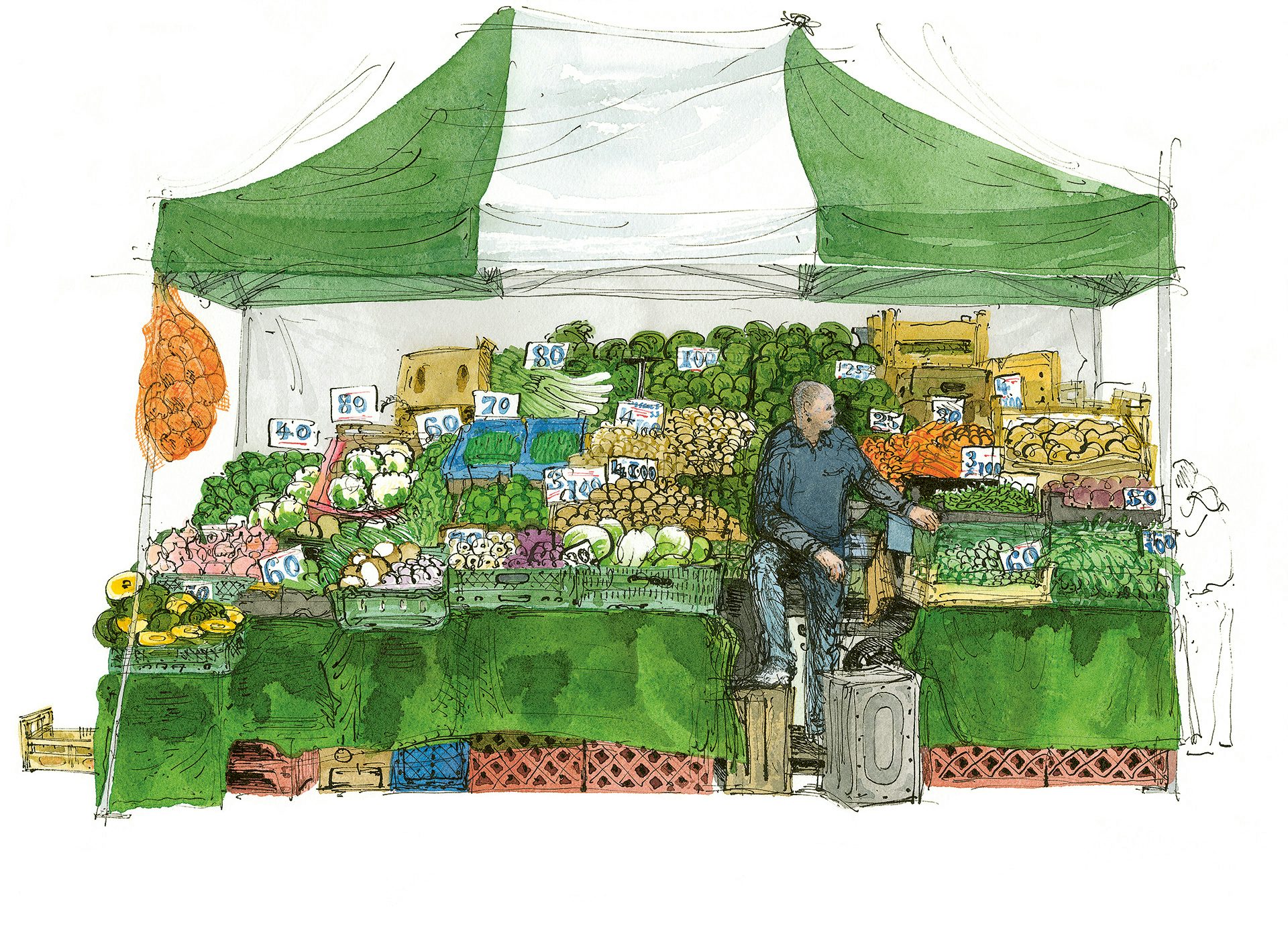

While many grow tired of London’s rapid expansion and hurried rhythm, David Gentleman’s outlook is a testament to Samuel Johnson’s famous quote that “when a man is tired of London, he is tired of life”. Born in Hertfordshire, the artist has called the city – and indeed, the same street – home for nearly 70 years, and if anything, he seems more transfixed than ever. His latest book, My Town – released to coincide with his 90th birthday – is filled with charming illustrations of the city’s myriad scenes, interspersed with musings on his home, studio and life’s work to date.

Much like the city itself, the aesthetic and scale of Gentleman’s work has varied on a continuous basis over the years. His wood engravings have been applied to everything from thumbnail-size postage stamps to New Penguin Shakespeare book covers to a mural stretching the length of the platform at Charing Cross Underground station. Adorned with life-size medieval figures interacting with the many fixtures, benches and entrances found along the platform, the mural was designed to draw a parallel between the workers who built the station and those who now use it everyday.

Following on from his wood engravings, Gentleman moved into working with lithography, which he used to depict scenes he encountered both in the UK and beyond. The artist has also produced a great number of other book covers, logos, menus, and posters – including a series for the National Trust and his hard-hitting anti-Iraq war designs. Nowadays, his time is primarily spent on watercolour drawings of the city that never ceases to inspire him.

Here, Gentleman talks to CR about his experience as a young creative in London following World War II, why he’s worked the same way throughout his career, and the stories behind his best-known projects.

Inheriting a creative streak That came very easily and very early in life, because both my parents were artists. They didn’t particularly encourage me to draw but they were doing it themselves, so it looked as ordinary as the other things they did, like digging the garden or washing the dishes.

They made it look normal and ordinary and just one of things that got done. They were very encouraging when they saw that I was interested, but I never, ever felt under any pressure from them to turn to this way of life.

Deciding on a creative education My education was fairly ordinary. I went to the local grammar school and I stayed on at the sixth form having done English and history and art. And I had to decide at that point whether I wanted to go to university or to art school. I thought very hard about this and I decided that what I most wanted to do was to go to art school. Then I went to art school and did national service, and then onto my main art school teaching which was at the Royal College of Art.

Life as a young creative in the post-war years Things were beginning to look up at that point. The war had left a depressing air of shabbiness and half-done stuff and bomb sites with nothing happening to them. But then in 1951 came the Festival of Britain and that was an exciting and optimistic time of my young life. And it meant that when I finished at the Royal College, I knew that what I really wanted to do was to work – and to work on my own – and my goal was to make sure that people saw what I was doing.

Working on the Penguin Shakespeare book covers They were lovely jobs to do. They were exciting to do because I knew the Penguin Shakespeare [series] at least would be seen by a whole generation of teenaged children at school. I thought, well, this will make an impression on them. It was a big job. I mean, that itself stretched out certainly over ten years.

On his longstanding affiliation with books I’ve always liked writing, and later in life I’ve come to write a bit in relation to my books. I think there’s a lot of common ground between the two [art and writing].

About the middle of my life, a friend who worked with a publisher asked me ‘why didn’t I do a book about England, or about Britain?’ I knew instantly that I’d like to do that, and after I’d been working on it for a few weeks or months, he said, ‘who are we going to get to write this?’ and I didn’t have a clue. He said,’“well, would you like to write it yourself?’ I was perfectly happy to do that and this became the first of six books which are all clearly in the same vein – three about different aspects of Britain, three about foreign countries, and between them [I worked on the books across] 20 years. I started them in 1980, the last one came out in I think 1997, so that was a good whack of a job. Since then I’ve done several other books of my own, as well as from time to time illustrating other people’s books.

Creating murals for the London Underground I was lucky with my clients from very early on. Early on I did some posters for London Transport – Transport for London as it is now – and about halfway through my working life, London Transport asked me to do murals on the Underground at Charing Cross. That was an absolutely lovely job to do. The technique I used was wood engravings which I had been very interested in early on in my working life.

When I started thinking what to do on the Underground, they didn’t really have any brief except to associate that station with the old Charing Cross that once stood there and had given it its name. That was all the brief was. And then I had the idea, not instantly, but very early on, because a tube platform is the same shape as a comic strip cartoon – the thin, long shape, divided up by things like the London Transport roundels, and the passages in and out of the platform. So I started with those things on the design and then so I built the design around them, rather than making a design and trying to fit these things in.

The other thing I wanted to do was [show] how the original Charing Cross had come about. The idea was drawing the people who would have worked on it, and then on the finished platform, the people waiting for the trains to come along. So [connecting] the two periods – the people building the station in the first place and seeing how equivalent they were to those workers beside them – that was the idea.

Experimenting with different forms and techniques Wood engravings were the thing that I did earliest. I started that really when I was at the RCA. And then quite a lot of my early jobs were wood engravings, and some press ads, some for quite big lavish New York limited edition books. And so that’s how I got familiar with wood engraving.

Because most of the wood engravings I did, and still are, fairly small, I think this led me to an invitation to do some postage stamps. I did a lot of stamps, particularly in the 60s when everything in that sphere was changing – it was a good time to be doing them.

At the end of that, I started doing lithographs, which were a very different technique obviously. I did a lot of lithos of London, particularly of Covent Garden, which was changing a lot at the time, and it was in danger of a big major road being run through the middle of it, roughly between Charing Cross Road and Holborn, Kingsway. A friend who lived in Covent Garden and was very keen on [protecting the area’s] future asked me to do a set of lithographs of the bits of it that were really endangered. I didn’t want them to become a campaign but I did like doing the lithographs, and they helped that scheme to be stopped.

It was a lovely thing to be involved with. I’ve been lucky throughout my working time getting one job leading unexpectedly to another, sometimes quite surprisingly different. Later on I designed quite a lot of posters for the National Trust, and some are lithographic, some photographic. I was interested in what you could do with photography as well.

Working the same way throughout his career I’ve never worked for any length of time with anybody else. Occasionally I turn to somebody else for a brief job, but it’s not the way I like working. I like not commuting, I’ve got a lovely outlook from the studio that I’m looking out of now, with the weather and the clouds and the leaves bursting out.

It’s just lovely – I love it. There’s no commuting. My commuting is from the kitchen, which is on the ground floor of my house, up four flights of stairs to the studio that’s at the top. It’s ideal. Nobody disturbs me up here.

Taking inspiration from a transforming London Every time I walk up and down either side of the river, there’s always new stuff to look at. As I look down on London from Parliament Hill fields on the edge of the Heath, or from nearer to me from the top of Primrose Hill, it’s all changed but it’s as interesting as it ever was. I feel that when looking at the skyline, but also looking at the new buildings that are going up all the time. Sometimes I think I could do without them but often they’re interesting.

That’s what I’m mainly interested in now. Really every aspect of it is interesting and it’s also something that if you start to draw it, you discover a lot about it instantly, even if the drawing is rubbish! It certainly makes me look at it in a new way.

Reflecting on his creative career while working on the book There weren’t exactly any revelations because I try to keep my archives in some sort of order, so I wasn’t getting surprised at things that I’ve done in the past, but it was good to be reminded of them. At the beginning of the book there are places I drew when I was a student, and there are very striking differences between then and now really throughout the book. I think [my style] has really evolved with stuff like growing up. You’re never aware you’re growing up!

My Town by David Gentleman, published by Particular Books, is available now; penguin.co.uk