The allure of the indie agency

From autonomy to workplace culture, leading creatives reveal what compelled them to start their own independent agencies and how they plan to keep their principles intact

Here’s a headscratcher. Why, after years spent climbing the ranks at well-known agencies or brands, would a creative step away to take on the responsiblity of running their own business? It’s not always how an independent agency is born, but there is certainly a pattern among many senior creatives: reaching the (perceived) apex of the industry, perhaps at a large network with all the resources and connections they could dream of, only to pack it all in and start from scratch with their own shop.

Far from being a case of giving up on the industry, we spoke to a range of indie agency founders who believe that carving their own path is the ideal way to get the best out of themselves, the talent around them, and the brands they could be working with.

“The world doesn’t need another agency, it needs better agencies,” says Ajaz Ahmed, the former CEO and founder of AQKA, who recently stepped away to set up a new London venture called Studio.One. “Like a lot of entrepreneurial adventures, Studio.One is born of the frustration and dissatisfaction with the ways things are. Everyone in the industry knows that clients and employees deserve better and that the old model is broken.”

This invariably stems from first-hand experience of how things are typically done at larger companies. “Our three founders all previously worked at smaller agencies that had recently been part of large mergers. Going from working nimbly and making decisions at speed, to being part of a much larger machine, with multiple layers of approvals, was eye opening to say the least. This bigger and more layered approach felt like it directly conflicted with modern media consumption, where speed to market is often as important as execution itself,” says Daniel Bonder at ImaginaryFriend in NYC.

“After many years as creatives at some of the world’s best agencies,” Bonder continues, “we had a lightbulb moment: our best clients often had creative teams themselves – in-house designers, editors, social media creators and more – but they still needed specialised expertise across channels, as well as big north star-thinking that only a third party can bring. Clients are no longer one-size-fits-all, hence why there were no longer as many AORs.”

Creatives are intimately aware of other gaps in the market. The founders of Berlin agency Presence felt that most advertising had become “empty” while London’s Baby Teeth was set up to properly bridge the gulf with the entertainment world. US studio Pinch was born because the founders saw potential in the emerging experiential design market that they didn’t think was being served, and Amsterdam agency DeepCuts co-founder Quintin van der Spek says he and co-founder Hiro Ikematsu felt there was “a disconnect between film editing and music that often led to inefficiencies.”

Sometimes, new ventures are made possible by circumstances lining up. Michael Brown at Pinch says he and his co-founders felt they were at the right point in their careers, while Fearless Union’s Al Fayolle said their founding team came together when their previous agency went into liquidation. But even these circumstantial factors are underscored by a motivation to offer something unique or overlooked.

We wanted to do something that let people’s differences and talents sing, to create a place where creative folk can share and learn from each other

This extends beyond the work itself to how things are run. The question of workplace culture was pressing for London creative studio The Cowgirls. Ali Alvarez says that she and her co-founders loved working their way up the creative industries, from network agencies to production companies to in-house. “But we’ve become parents and the balance of work versus being a present and involved mum just doesn’t tip our way. And we were getting sick of it.

“So what do three ambitious, restless creative women do after they’ve had these jobs and have also become hyper-efficient mums … but aren’t willing to pack it in for a ‘better life’? They walk away from the big job and see if they can find a new way to do it on their terms.”

It’s not just about work-life balance but instilling a sense of empowerment within colleagues, too. Uncharted was founded partly to do away with permission culture. “We wanted to do something that let people’s differences and talents sing, to create a place where creative folk can share and learn from each other, and where there is space for clients to be part of that experience, too,” says its co-founder Laura Jordan-Bambach.

Brown says this has been a bigger part of the focus at Pinch than even he anticipated: “What has turned out to be far more important to our success and growth is recognising and advancing talent, and from a process perspective, not codifying good design, but more trying to remove barriers and time constraints for the team.”

We want to do as much as we can, and be successful financially. But for us, breadth and quality are really important measures of growth too

Grace Francis recalls having the “next ten years mapped out at networks I respected”. Their perspective began to shift during conversations with agency groups interested in backing a potential venture, sowing the seeds of inspiration for what would later become their London-based studio Wonderful Things.

However, when it became clear that the backing came with too many strings attached – unreasonable targets, sacrifices to work-life balance – the three founders set out on their own, writing a new business plan that meant they could “fly solo without investment”, and therefore without the demands and targets from upstairs.

“We asked, what would it mean to be able to say no to the climate-criminal’s pitch request, to say yes to the arthouse client, to put boundaries on working hours, to protect the people who worked for us? To make something simply because we wanted to make it,” Francis says.

All of the founders we heard from agree that to continue building these workplaces and uncovering new opportunities, they will need to achieve growth (“I track EBITDA as if we were in year five,” admits Francis). However, everybody unanimously spoke of doing so on terms that allow them to continue living their founding principles.

This might mean redefining typical definitions of ‘growth’ or ‘success’. “Of course we want to do as much as we can, and be successful financially. But for us, breadth and quality are really important measures of growth too,” Baby Teeth’s founders explain.

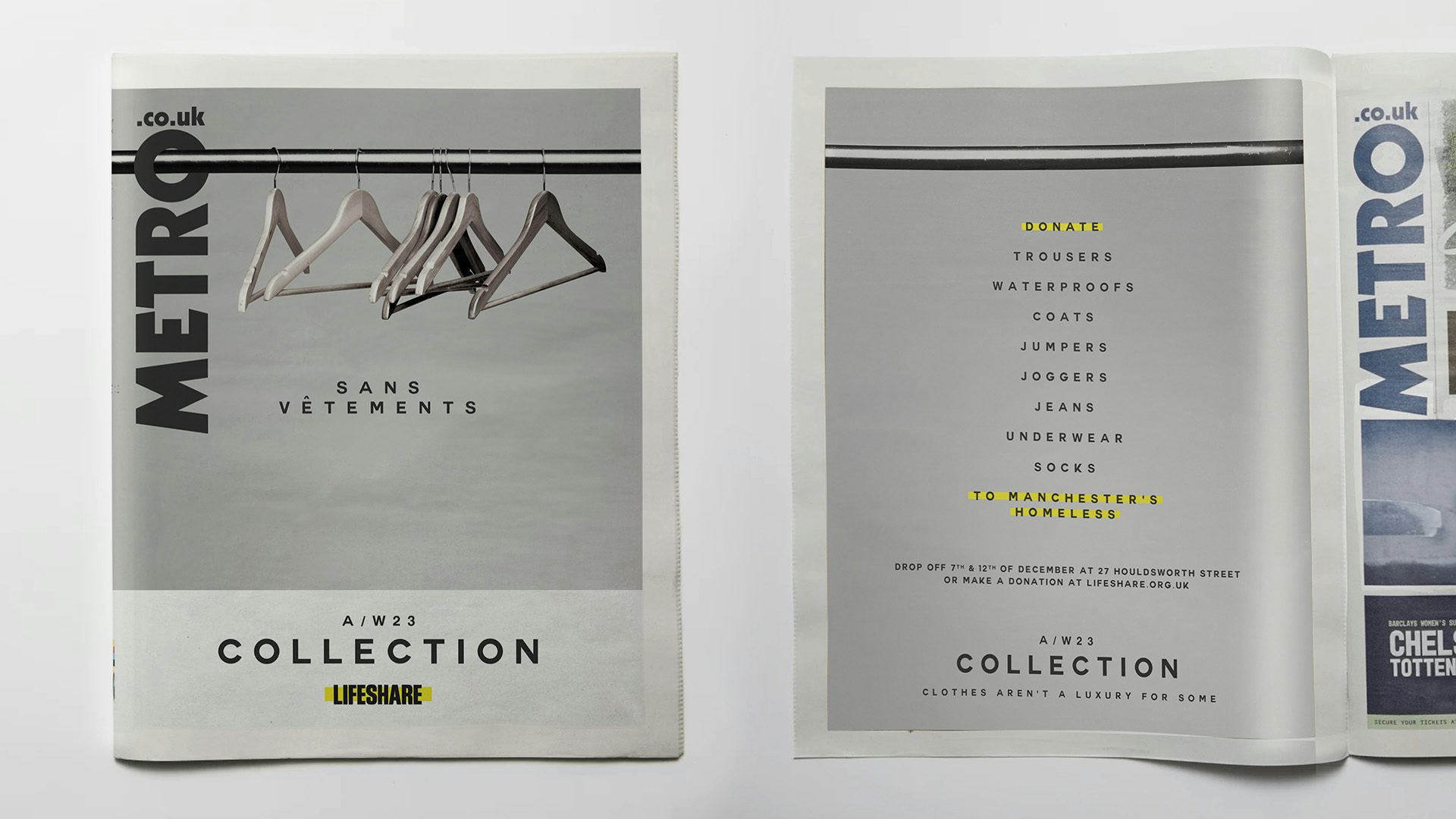

“Growth is important but not at all costs,” says James Cross, co-founder of Manchester agency Meanwhile. “We don’t want to lose the culture we created when it was just three of us in a room feeling like we could take on the world. If we become too big, we’ll lose that, but we’ll have to tell you when that is because we don’t really know! We want to be a reference point for the best creative work in our industry and beyond, it’s that simple.”

Alvarez at The Cowgirls flags the importance of growing the people side carefully. “There are a couple of people we are desperate to rope in as Cowgirls and we know that their skills will just add to the business acumen of the studio. When we add the people in, it’s to supercharge the ideas or the process of making them – so they’re as high-performing as they can be on all fronts.”

Denise Orman and Diego Gueler Montero at Buenos Aires-based agency Zurda are already experiencing geographic growth, engaging with clients outside of Argentina and working on expanding the agency into Mexico, too. But despite their ambitions even at this early stage, they will always have one eye on making sure they break the cycle rather than repeat it. “The idea is to grow without turning into the kind of place we once wanted to escape from.”