Looking back at another blockbuster year for Netflix

Netflix continues to dramatically disrupt the film and TV industry, overturning long-established models with seeming ease. As part of our Annual 2019 coverage, Tom Seymour looks back at another big year for the brand

It may be an apocryphal story, but Reed Hastings is said to have come up with the idea for Netflix after his local Blockbuster store asked him to cough up $40 for an overdue copy of Apollo 13. The platform is now available in more than 190 countries, and has over 83 million subscribers. As the story of Netflix is written, 2018 will possibly be remembered as a landmark year. Last year alone, Netflix debuted more than 700 original releases across movies, TV shows and comedy specials. To create this much original content, and distribute it via one’s own platform and nowhere else, is almost unheard of in the history of TV and cinema.

The Hollywood studio system has always owned the stars and created the content. The films were their intellectual property; the rental platforms only existed to distribute their original programming. Netflix’s aggressive foray into both production and distribution is an inversion of a tried, tested and enduring industry arrangement. It is, in other words, a massive, audacious power-grab.

This new model can be traced back to 2013 and the creation of House of Cards. The series was created and produced by Netflix and streamed exclusively on the site. You had to buy an overall subscription to view it. The show cost Netflix in the region of $100m and received 21 Emmy nominations over two years. It became the template for Netflix’s current model.

Its latest disruption came at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. Roma, the long-awaited semi-autobiographical film by Alfonso Cuarón, was due to play at the festival. It was Cuarón’s first film since Gravity, and the presumption was Roma would be sought after, that after a gala competition screening at Cannes it would be snapped up by one of the big studios and treated to all the bells and whistles associated with a big cinematic release.

Then, to the shock of the industry, news broke that Netflix had acquired the rights to Roma and would stream the film exclusively on the platform. It was another ambitious power-grab by Netflix. Cannes responded by dropping the film, citing that it did not cater for movies purely backed by SVoD platforms. After the Cannes fall-out, the Venice Film Festival stepped into the breach and Roma won the Golden Lion.

As a producer of the film, Cuarón was very involved with the deal that his backer, Participant Media, struck with Netflix. There was plenty of interest in Roma from all the traditional distributors, but Cuarón decided to go with Netflix, in part because of the “diversity” of its audience. “Netflix understood this film,” Cuarón told Screen International. “It was not only its ambition towards the film, but the aggressiveness of how it wanted to do things.”

Netflix is continuing to diversify its output. Reports have it entering negotiations to buy the Egyptian Theatre in Los Angeles, a grand movie house on Hollywood Boulevard, for a price in the “many tens of millions of dollars”, according to Deadline. Meanwhile, Bloomberg reported that Netflix will publish a high-end self-promotional print quarterly, which will be edited by Vanity Fair veteran editor Krista Smith, a fixture of the magazine’s Hollywood coverage. With a working title of Wide, and more than 100 pages in length, the magazine will include essays and features about the brand’s programming.

In another splashy moment last year, and after months of speculation, on December 28 Netflix released a feature-length extension of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror series. Titled Bandersnatch, the film was interactive – a ‘choose your own adventure’ format more associated with video games. Fans got to work trying to decode the film’s numerous narrative branches and analysing its symbolism. Netflix experimented with this type of interactive format in 2017, but Bandersnatch is its first big success.

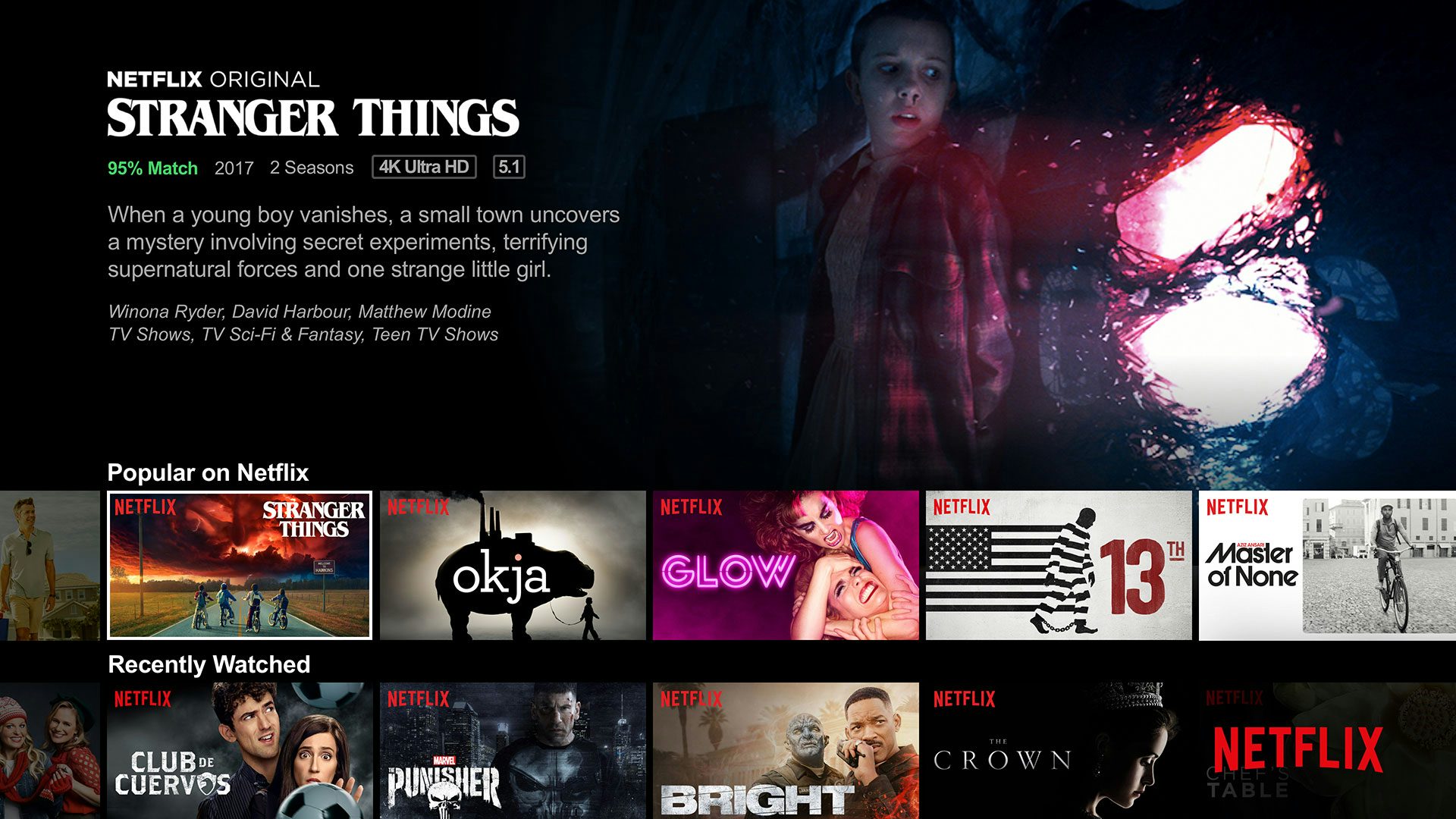

Beyond content, Netflix has also focused on finding innovative, and often irreverent, ways of promoting its new IP. For the launch of the second season of Stranger Things, for example, Netflix funded the opening of numerous immersive bars full of the show’s signature tropes in major American cities before closing again as the show’s promotional run neared its end.

For the launch of Bandersnatch, it invested in a pop-up store inspired by the show at London’s Old Street tube station. The 80s-themed shop, named Tucker’s Newsagent & Games, was decked out with promotional materials for some of the Tuckersoft games that feature in the Netflix programme.

The company has also invested heavily in finding new ways to diversify its revenue streams while not subjecting customers to the pain of having to sit through commercial adverts. This comes in the shape of ‘marketing partnerships’. Viewers will not to be subjected to commercial breaks but will see Netflix-owned characters used in other companies’ commercials – effectively, Netflix will license out popular characters and personalities from its many shows.

In a sign of the company’s attempts to be seen on an equal footing to the doyens of Hollywood, in February Netflix unveiled its new logo animation. It started to appear before all Originals released from February and is now being retrospectively added to other TV series and films. Netflix tweeted that the logo “shows the spectrum of stories, languages, fans and creators that make Netflix beautiful – now on a velvety background to better set the mood”.

Netflix is a giant – a multifaceted company with far more control over the film business than Blockbuster, its original rival, ever exerted. One statistic exemplifies its influence: according to Keating, Netflix subscribers now use 35% of America’s entire internet bandwidth by streaming movies in the evening.

The phrase ‘Netflix and chill’ has now entered the vernacular, an accepted milieu of modern life. But, whatever happens next, don’t expect Netflix to chill. Hastings and Co seem hungry for more.