“Winners don’t write manifestos,” jokes Scott King, who, all the same, has just finished writing one. It’s hard to believe that King – a former art director for i-D, creative director for Sleazenation, and professor of visual communication at the University of the Arts London – really belongs in the ‘loser’ camp, but his comment is only half in jest.

“The author is almost inevitably thwarted in some way,” he continues. “Ad agencies and certain aspects of government might see themselves as winners writing manifestos, but culturally, or in the arts, they’re written by losers. [Filippo Tommaso] Marinetti was a loser. Wyndham Lewis was a loser. It’s trying to agitate, and lay out how they think things should be, and they’re often written by cranks and outsiders. I think I might include myself in that.”

Manifestos arguably sit awkwardly within brands, or even big design or ad agencies, although writing a manifesto has become a trend in recent years, used as a way to spell out a company’s philosophy or ideology. Yet some might feel they would do well to steer clear of these documents, which are often thoroughly defanged once they’re in the service of big business.

“If someone was going to take a subject and clarify it for the good of many people, I think that’s the ultimate reason for a manifesto,” King says. “But it’s misused. And it’s either the lone crank who wants to create a space for themselves, or a cynical ad agency or government that want to appear to be saying the right things. But I’m on the side of the lone nut who’d consider writing one in order to make space for themselves, in order to create work.”

Self-deprecation aside, King’s own effort, entitled the Debrist Manifesto, is an attempt to encapsulate his own artistic frustration and what he sees as a failure to bring all the creative flotsam and jetsam of his mind to life. While the artist says he yearns to be constantly occupied, the reality doesn’t always match up, leaving his inbox stuffed with unrealised ideas.

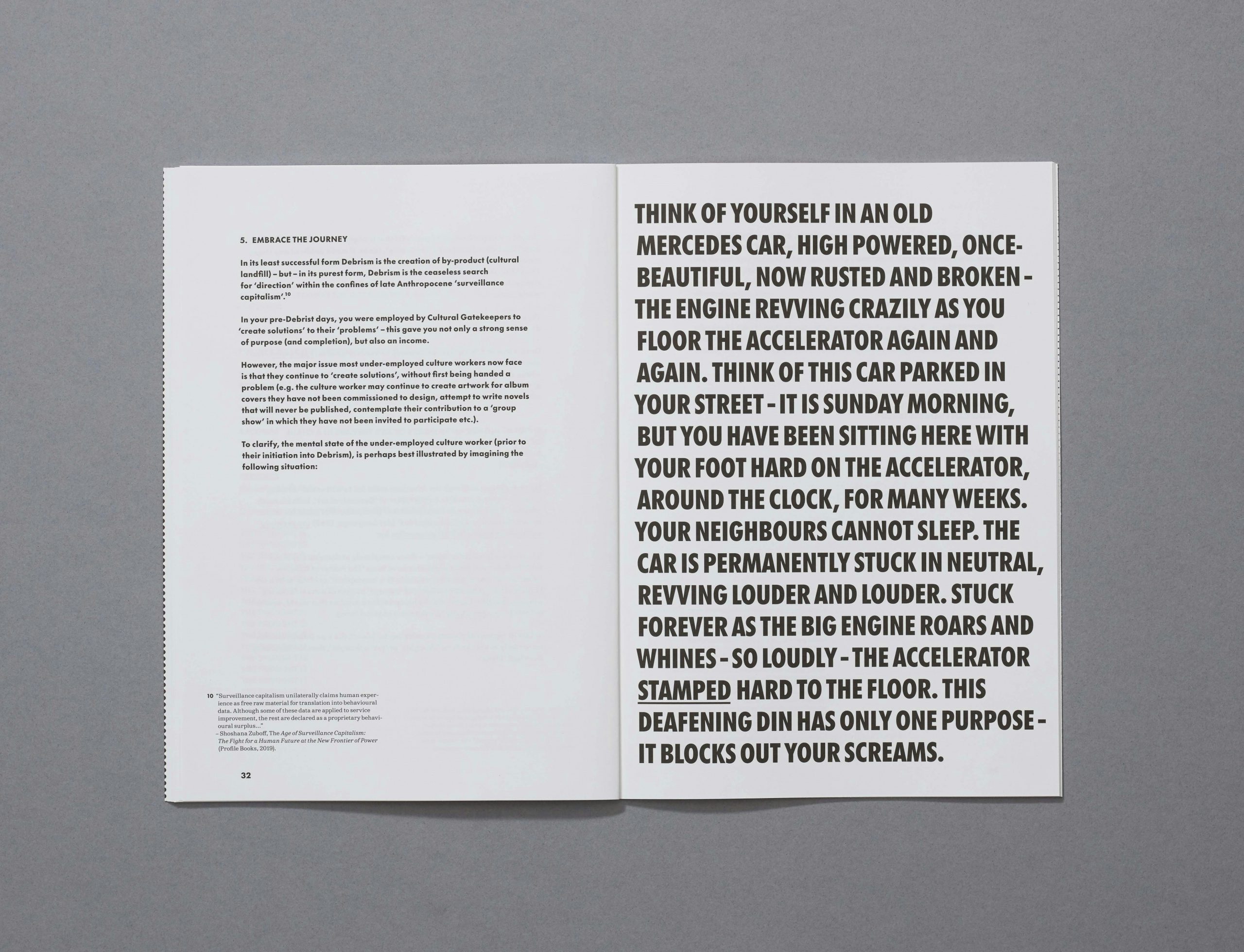

“I’ve got literally thousands of emails I’ve sent to myself, like Alan Partridge making his notes for himself,” he says. “It’ll be an idea for a play, or an idea for an opera or a painting. All these things I can’t really do but imagine I can. And on my desktop I’ve got hundreds of files, all of these half-started projects. It occurred to me that what I really do is make debris, mostly. Some things see the light of day, or you’re commissioned to make something, and some things emerge. But most stuff is beneath the surface, and that is my real life. And that is what the Debrist Manifesto is about – it’s about real life. Not being able to match your imaginary output to your concrete outlet.”

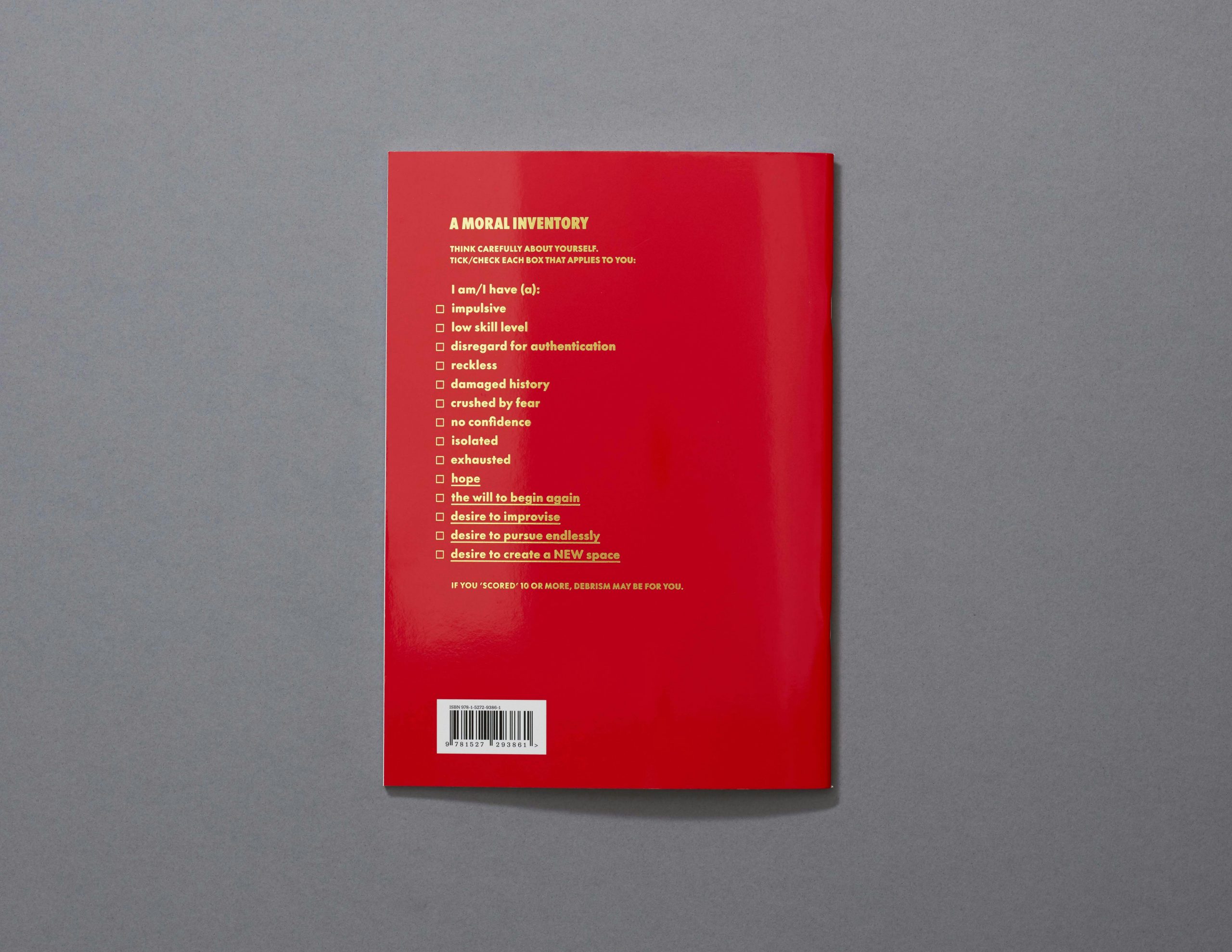

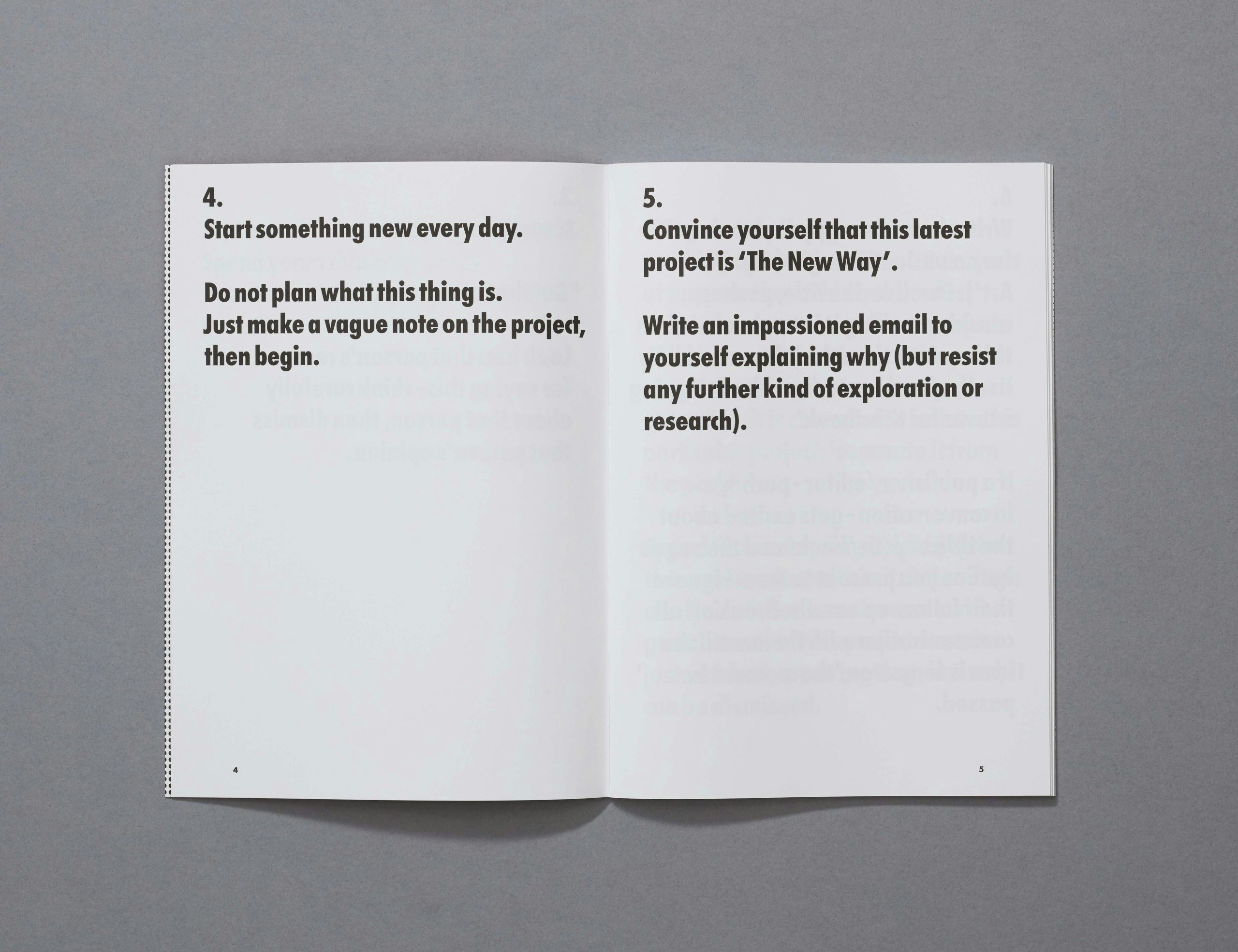

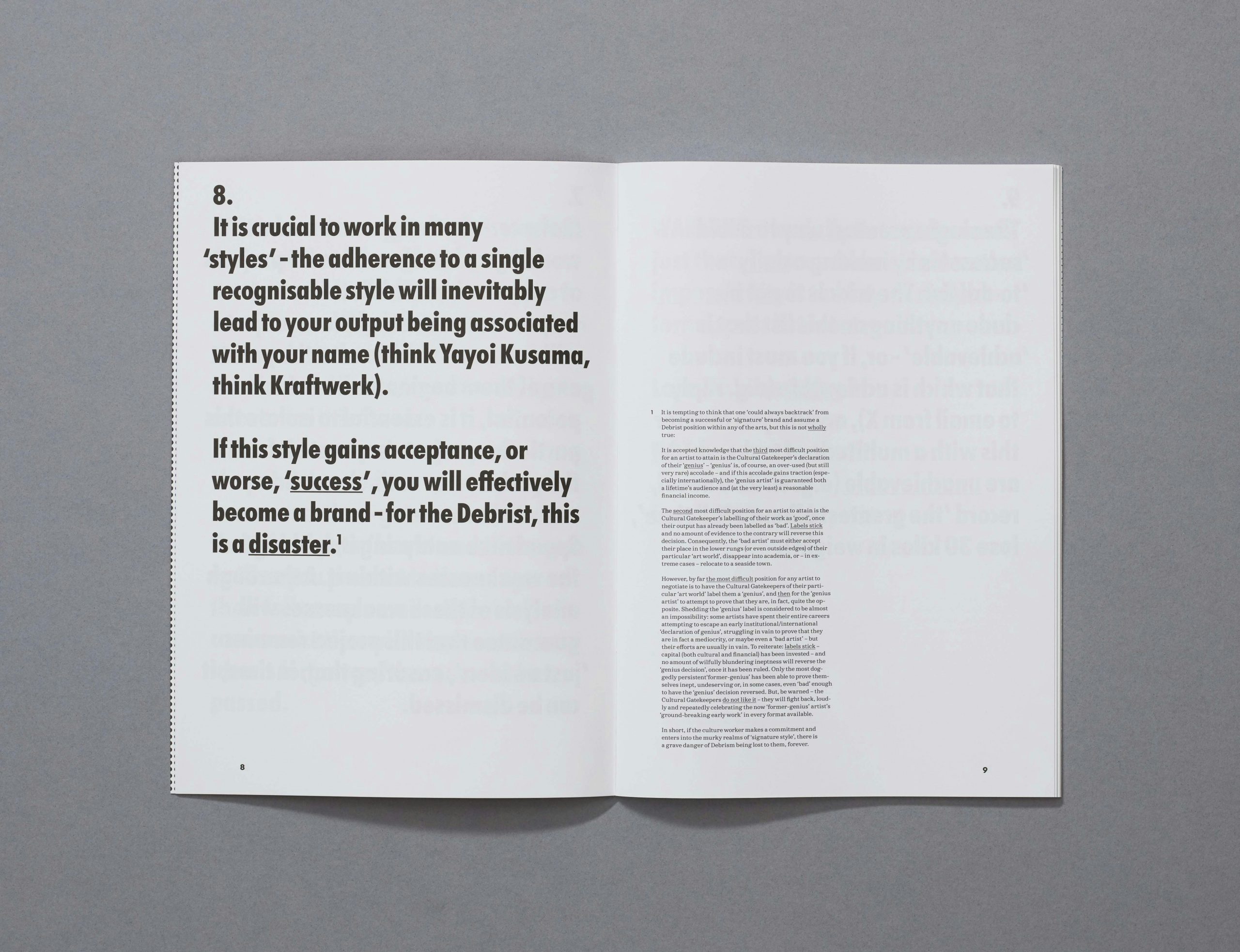

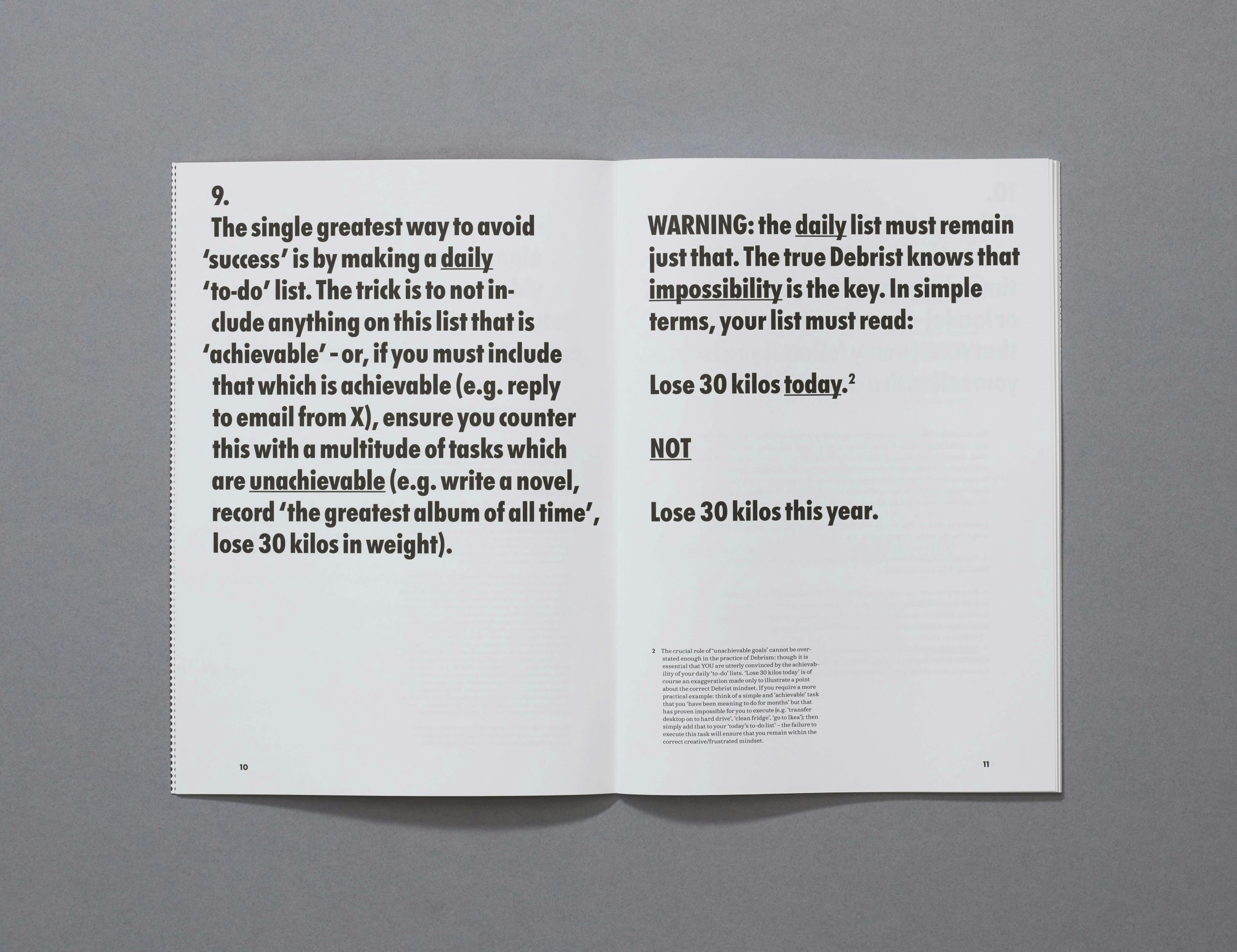

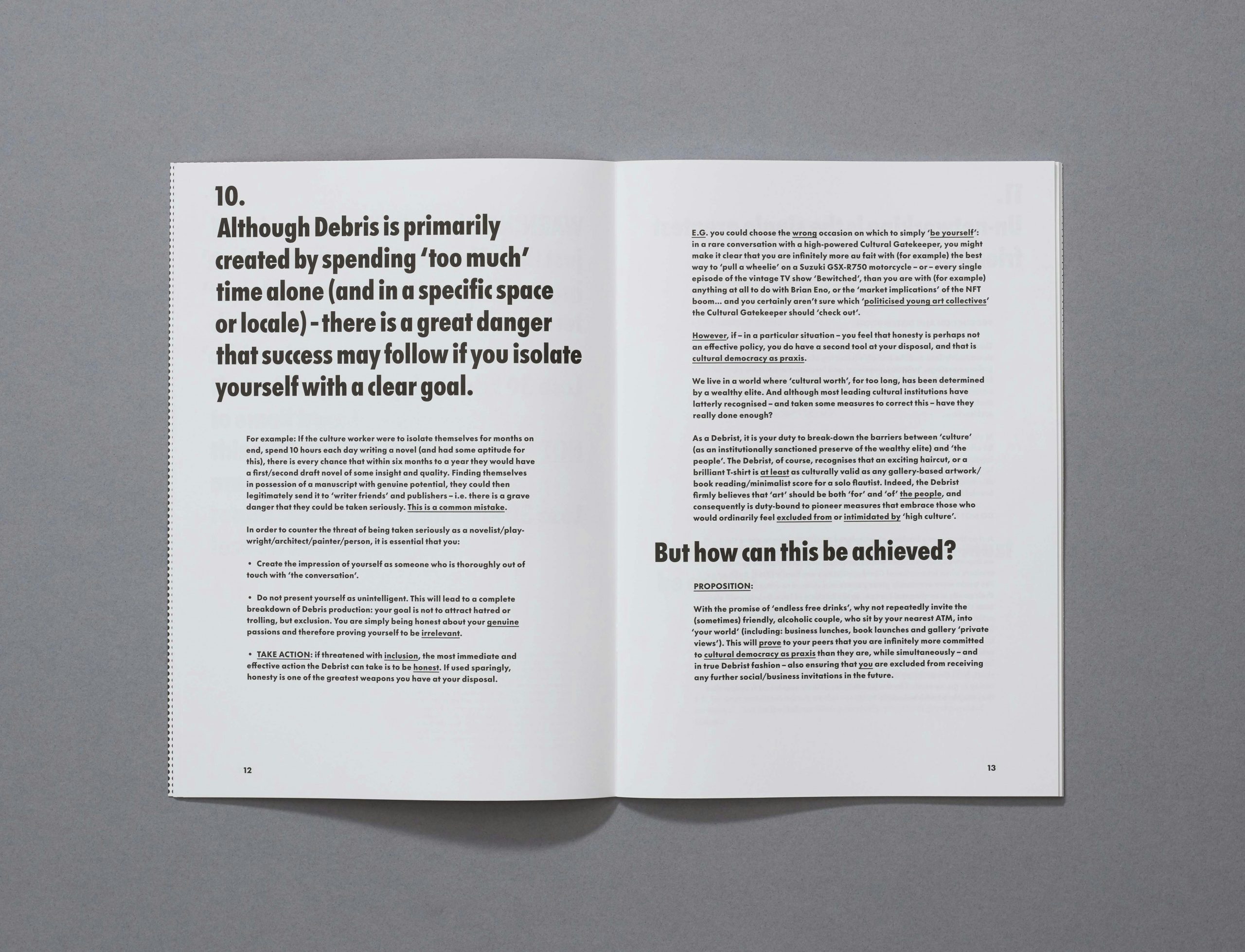

Most readers can probably relate to King’s words, and indeed parts of his manifesto feel like they could be aimed squarely at the ad and design industry. “Make certain that you are never working on fewer than 12 to 20 projects at any one time,” for example, or, “If you finish something, disown it. Spend years thinking about how much better you could have done it.”

Although satirical in tone, King’s manifesto neatly captures those creeping feelings of futility that many creatives will have faced at one moment or another. “If the world worked as I wanted it to work, every idea I had there’d be someone stood next to me wanting to make it,” he adds. “Or somebody who wanted to give me £20k to do it. The Debrist Manifesto is very much built on my truth.”

What compels King, and all the many other manifesto writers, to create these documents? He likens it to clearing a space in a forest to make room to work. “A manifesto is always about idealism – whether those ideals are hideously wrong or absolutely right,” he explains. “It’s that person’s perceived vision of idealism. It’s about trying to right wrongs – whether they do that or not.

“If you look at the most famous manifestos, like Blast! or Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism – which are now perceived as being quite fascistic – they have an element of that. They’re really about trying to rock the status quo … a manifesto has the potential for change – that’s the whole point – but it’s also a fantasy.”

There’s the sense that what makes manifestos so appealing is that they function as their own perfect microcosms. They offer an easily digestible format, and also, says King, an innate confidence that the writer really knows what they’re talking about. In them, creatives, agencies or brands can set out their dos and don’ts with little need to consider the demands or rules of the real world. Or necessarily offer concrete solutions.

How that translates to life then becomes another story. “A manifesto, in many ways, is a bureaucratic weapon,” says King. “The exciting thing about a manifesto is that it should be a single author, who probably has no power. Then that becomes interesting. When it’s used by ad agencies or governments, you know it’s not really a manifesto. It’s a bureaucratic blurb. An apology. And it’s not towards taking action.”

As King highlights, manifestos can be abused as a “band aid” for bigger social issues. It’s all too easy for a person or company to write one that pays lip service to these challenges, without taking the next step and actually addressing the problem. In some cases, manifestos even become “perverted by their own use”, as King puts it, when others accidentally or wilfully misinterpret what they mean.

So are they actually of any use? Aside from their charm, what’s the point of writing them? For King, they respond to people’s innate need for a set of rules to live and work by. “The presumed need for a manifesto is to try to live a life of clarity and direction, which functions no differently to somebody religious or who’s done a 12-step programme,” he explains. “You want to adhere to these rules. You want to go to bed with peace of mind, knowing you completed your list and acted by your manifesto, but you rarely do.”

A manifesto is always about idealism – whether those ideals are hideously wrong or absolutely right. It’s that person’s perceived vision of idealism

They also, perhaps, offer a degree of therapy. King’s own manifesto, he says, has helped move him beyond the “brick wall” he’d hit with work. Having completed it, he now plans to work in a different way, relying less on printers, screenprinters and photographers to bring his ideas to life, and make more work away from the intervention of “cultural gatekeepers”.

“My manifesto is about doing it yourself … and not necessarily feeling obliged to work within the systems you have, which are guarded by others,” he concludes. “It might be fantastical nonsense, but I wrote my manifesto in order for me to progress in myself.”

The Debrist Manifesto is published by International General, priced £20; available via scottking.co.uk