So you want to set up a design festival?

Following the first edition of the Birmingham Design Festival last month, we speak to co-directors Daniel Alcorn and Luke Tonge about not having a life for nine months, plane-related near disasters and giving the city’s creative community something to shout about

The UK’s design festival scene has been going from strength to strength over the last few years. This September will mark the 15th year that London Design Festival takes over the capital for seven days of talks, workshops and exhibitions, while newer players such as Design Manchester and Graphic Design Festival Scotland have helped ensure that the country’s creative scene isn’t too London-centric. The Midlands however, has been somewhat neglected from the party – at least up until now. Giving the region an injection of life was the task Dan Alcorn and Luke Tonge thrust upon themselves when they decided to set up Birmingham Design Festival, which took place for the first time last month.

The two designers first met several years ago at one of the events held by Badego, a Birmingham-based creative meet-up run by Alcorn. Originally from a market town called Banbury outside of Birmingham, Alcorn previously worked as a digital designer at Aston Villa football club and is now at local studio Substrakt, which makes websites for arts organisations such as the English National Opera and Shakespeare’s Globe. Tonge’s background is more print-focused, having worked on magazines such as travel publication Boat and Monotype’s title The Recorder. When Alcorn decided to make the step from running smaller-scale events at Badego to founding a fully fledged design festival, Tonge’s different set of skills and broad range of contacts in the print world made him the obvious choice as co-director. Their shared mission in setting up the festival was clear from the offset: putting Birmingham on the map.

“I’ve always found it a bit crazy that Birmingham has not had a design festival of this ilk. I thought it was an important thing to happen to help establish Birmingham’s design industry, because it needs a bit of a spotlight shone on it. There’s a lot of really good agencies here that don’t shout about themselves, but also Birmingham as a whole is having this really big regeneration and becoming a very vibrant, lively place to live,” says Alcorn. “Doing something like this was important in order to show designers around the country that this could be a really good place to set yourself up, and stop people graduating from BCU going to London because they think there’s nothing here.”

While creative meet-ups like Badego and Glug didn’t have the best turnouts when they first came to the city, the tide started to turn over the past year when Alcorn’s events regularly started selling out. “It was just a realisation that now’s the time. Birmingham is ready for this, there’s an appetite for it,” he says. “There was a little bit of a risk that we took because we weren’t sure exactly how big that appetite was, but it turns out having now done the festival that it was definitely there.”

The first step in making BDF a reality was working out where the hell to start. Alcorn and Tonge started to pull together a team who were willing to commit the next nine months of their lives to building an event from scratch for no money whatsoever, comprising industry contacts from Birmingham, people already running similar events and others who they had worked with before and knew would slot in easily.

Next up, the team had to decide how the festival was going to look and feel. “I always had a plan in my mind of what the festival should be, and that it should have districts. They were a bit more granular when I initially conceived it in my head, but it was the idea of grouping things together so that people could really immerse themselves,” says Alcorn. “We had a bit of pushback from the team because we initially talked about 10 venues, and even that was quite a daunting task. People wanted to do it in one and just have it as a conference, but I liked the fact that people were walking around and experiencing Birmingham as they experienced the festival.”

In the same way, the designers were keen for the festival not to mirror the price point of more traditional (overpriced) creative conferences. “The goal of the festival was always for it to be extremely affordable,” says Alcorn. “We both find conferences and festivals to be really extortionate and don’t really see how anybody benefits from them being £500 plus, because the only people who can go to them are those who have already established themselves and are making more money. Anybody who can really benefit from those talks is immediately priced out.” This then led to the split between day and night formats, which saw all of the day talks put on for free and the main evening event being ticketed.

Many of the speakers for the evening talks came on board for free straightaway, including Marina Willer and Craig Oldham, which went a long way in helping the festival’s team to establish its own identity. “A lot of those existing friends became the reason we knew we could do the festival because we then spoke to other people and said ‘look these guys are on board and this is the kind of event it’s going to be’,” says Tonge. “All those connections gave it more legitimacy and gave other speakers the confidence that we were a real festival, not just two guys having a bit of a stab in the dark.”

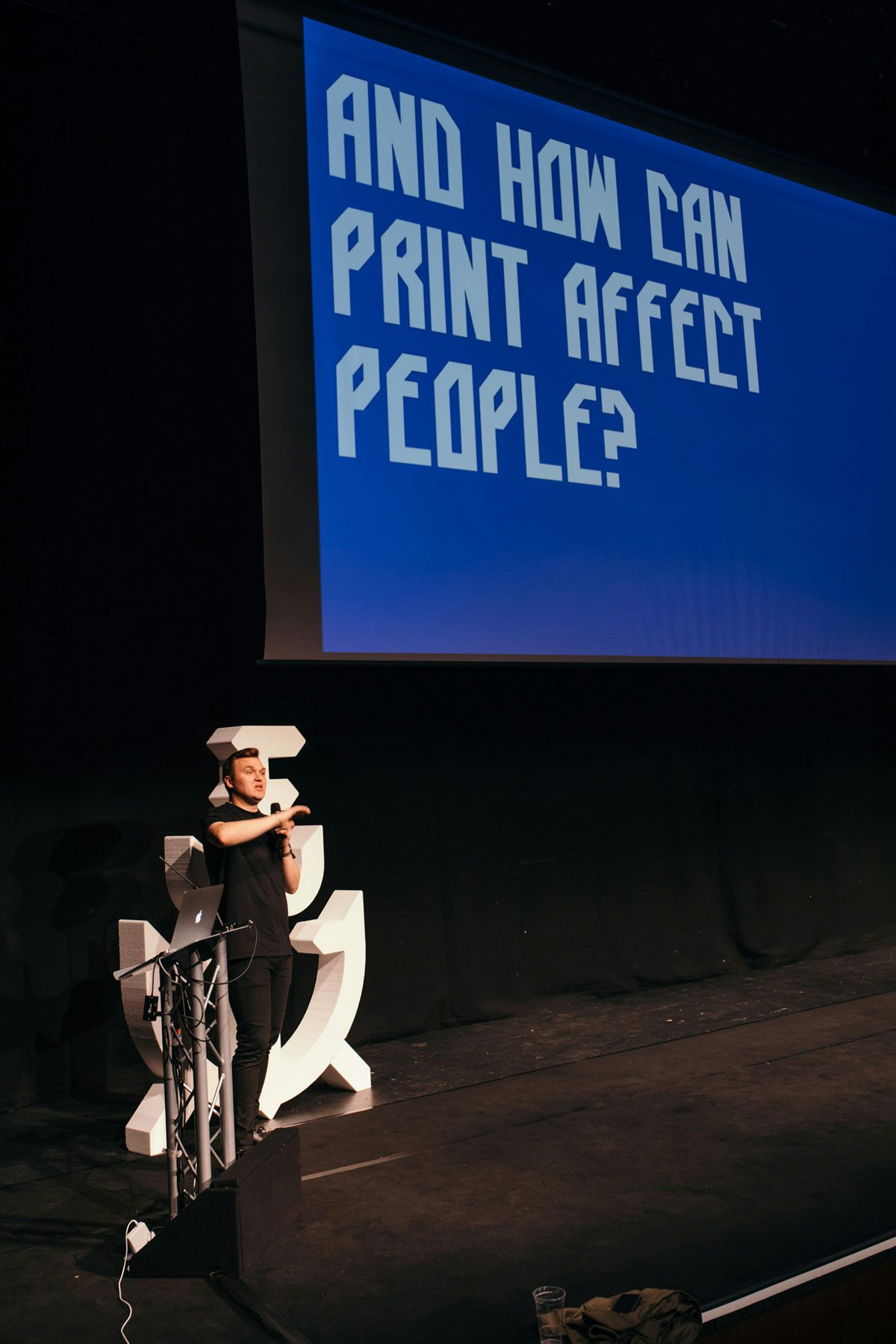

Having said that, the designers also didn’t want the festival to add to the cultural echo chamber created by other events like this, by relying on the same big names to draw in crowds – a criticism recently explored by Manchester Art Gallery’s exhibition Speech Acts. “We needed the Anthony Burrills and the Aaron Draplins to shine a bit of a spotlight, but going down from that list it was people who we were really interested in hearing talk. None of these people have spoken in the Midlands before bar a very small handful, so that gave us quite a big pool of people to bring in,” says Alcorn. Bigger names weren’t just reserved for the evening talks either, with daytime slots being filled by the likes of art director Kuchar Swara and Studio Output’s Johanna Drewe.

Diversity was another big sticking point for the team behind BDF, a challenge not helped by the fact that their initial call for entries resulted in 75% of applications coming from men, and staggeringly only one non-white applicant. “We were contacting agencies asking them to consider the speakers that they sent, [and] if it was not a white man with a beard then that was a welcome decision from our point of view,” says Alcorn. “When you’re trying to go through this as a team it all feels really seedy because it feels like you’re labelling people, but unfortunately it’s those kind of conversations you need to have because otherwise you will just end up with a whitewash of a festival.”

Despite the teething problems caused by issues such as ensuring a diverse lineup, knowing how much things were going to cost and when, and a relatively cheap ticketing system, fortunately the team hasn’t had to deal with any major disasters during the festival’s infancy. There was only one, Draplin-shaped near disaster, Tonge admits. “Probably the biggest wobble we had was when we were looking to book Draplin’s flight, and when we went to book it the next day it had gone up by £1,000, which was ridiculous based on our budget. We had to wrangle with the airline and just keep trying, and luckily a few days later it went back down to the original price.”

As for what the future holds for the festival? Alcorn and Tonge are 100% committed to putting on the event in the same spirit next year. After that, they are open to exploring what other forms it could take. Regardless of how the festival may look and feel in the future though, they are both in agreement that its essence – celebrating the city as both a destination and a design scene – should remain the same. “We’ve called it Birmingham Design Festival for a reason, we didn’t give it some obscure name,” says Tonge. “We wanted to be very clear about what it was, and that it’s for Birmingham.”

Birmingham Design Festival took place from 7-10 June 2018 at various venues across the city;

birminghamdesignfestival.org.uk