How virtual culture is evolving amid the pandemic

With exhibitions, live productions and art fairs shuttering during the global coronavirus outbreak, we explore how virtual initiatives hold up against the real deal – and what this means for the future of culture in digital spaces

Witnessing Covid-19 take its toll around the world has felt akin to watching dominoes toppling over, one by one. As the arts community catches up to the reality of lockdown, institutions are pushing out new digital initiatives ranging from digital events to virtual exhibitions to Instagram artist takeovers.

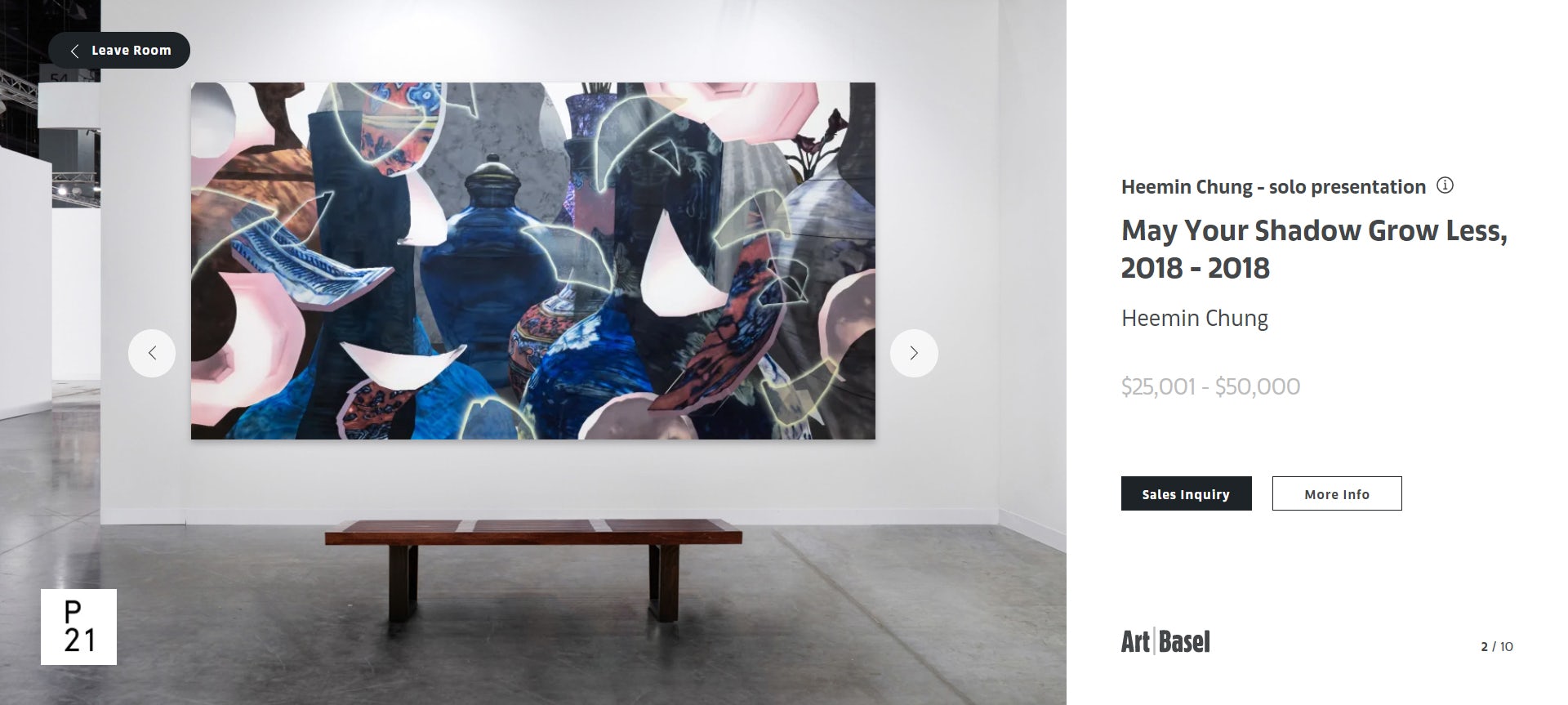

With China being the first to implement strict lockdown measures, Art Basel’s March plans went in a markedly different direction than usual. Last year, the Hong Kong edition of the world-famous art fair drew in a record crowd of 88,000 visitors. This year, the arrival of the pandemic meant it had no choice but to go fully virtual for the first time, with Online Viewing Rooms, which hosted galleries’ collections for buyers and collectors to peruse and, hopefully, purchase.

If Art Basel seemed remarkably quick off the blocks in their solution to the Hong Kong cancellation, it’s because it was already part of their plans prior to the pandemic. “We had been planning to launch Online Viewing Rooms as part of our ongoing efforts to use new technologies to create additional opportunities to support our galleries and foster a healthy art-world ecosystem,” explains Marc Spiegler, global director of Art Basel. The platform was conceived to help exhibitors showcase artworks that don’t make it to their stand at the fair; with no artworks making it to the fair this year, it was Art Basel’s best option.

Creating any kind of digital experience for the arts comes with its own set of challenges – namely showcasing the works in their fullest form. For Spiegler, their aim was never to create “a simulacrum of the show experience”, since it was designed to be a complementary platform running in parallel to the art fairs.

“Our intention was not to replicate a visit to the fair itself as we believe that digital platforms cannot replace the experience of seeing art in person. Collectors don’t come to fairs exclusively to buy work, just as gallerists don’t only participate to sell the works on display,” he tells us. “Both collectors and gallerists attend our shows to exchange ideas, deepen existing relationships, and to develop new connections. In a market built on trust, face-to-face interaction remains essential.”

Of course, face-to-face interaction is hard to come by under current circumstances. However, as many will testify, these days even seeing a human on the other end of a phone or laptop screen beats the alternative of seeing no-one at all (or at least no-one new). It’s something that rang true for the team at London-based theatre company Headlong, which is working with Century Films on bringing new, live theatre productions right into our homes. The series of shows, titled Unprecedented: Real Time Theatre from a State of Isolation, is set to launch mid-April, and takes the form of short ‘digital plays’.

The themes handled in the plays come in direct response to the pandemic, promising to touch on how ideas of everything from community to capitalism to the climate are “evolving on an unprecedented scale”. The Headlong team commissioned 18 playwrights – including James Graham, Clint Dyer, Jasmine Lee-Jones, and Duncan Macmillan – to write the scripts, with a handful of directors and over 20 actors tasked with bringing the stories to life.

Contrary to Art Basel’s serendipitous head start, Unprecedented is very much off-the-cuff. The initial concept came from Holly Race Roughan, associate artistic director at Headlong, who had the idea as soon as the pandemic broke. “It came from quite an organic place of going: ‘we need to respond to this artistically’. Our audience is saturated with news and saturated in social media – we’re all talking about coronavirus all the bloody time! And it feels like we really need to process what’s going on around us through art as well as through memes and Twitter and everything,” she tells CR.

Creativity often comes from limitations, and there’s such an obvious limitation right now that actually there’s a hell of a lot of creativity

Race Roughan had originally suggested a response along the lines of a 24-hour, round the clock play. Yet Headlong artistic director Jeremy Herrin saw an opportunity to flesh it out into something bigger, and so the team set about compiling a list of writers that Headlong had already built a relationship with. “We were expecting maybe four or five of them would get back and say ‘yeah alright, I’m on board’. Almost 80% of them got back and said yes,” says Race Roughan. The directors were given a week to write a five- to ten-minute script for up to 12 voices, with some doing solo pieces, others writing six-handers, and even some musical theatre. After that came a week of casting, before redrafting and rehearsals. The plays will be rehearsed, performed and streamed all through video conferencing platform Zoom.

“It’s like the equivalent of rehearsing on set. So what they’re writing for is, for example, a grandmother talking to a grandson, and one’s in one screen and one’s in the other. So we’ll be rehearsing in the very form that the plays have been written for,” Race Roughan explains. “The idea is that everything needs to be rehearse-able and performable from isolation. So if you write a play about a couple who are talking to their grandparents, then we’d need to find two sets of actors who are genuinely living together so you can get four actors across two screens.”

Race Roughan and the team are realistic about the limitations and potential teething problems. The ambition is to broadcast everything live, but in reality they’re likely to pre-record some plays and hopefully stream a handful live. Likewise, the sets are restricted in terms of their design (“you can write [a script] that’s set in an office and we will do our best to achieve that!”), though she expects the stories to be set largely in gardens, kitchens, or even in bed. “Interestingly, the limitation itself feels very freeing,” she reflects. “Creativity often comes from limitations, and there’s such an obvious limitation right now that actually there’s a hell of a lot of creativity.

While Headlong has previously produced short films, this is new ground for the team – and they’re embracing that fact. “We’ve never made digital plays – we don’t even know what that is. We’re just having a crack at making it up!” Race Roughan says. “It’s exhilarating and a bit scary. At its heart it feels like there’s a generosity among the artists going, ‘let’s do this, because it’s important that people get to have access to art in this period that’s really in tune with what the fuck is going on!’”

There’s undoubtedly an advantage where video or performance can be used: London’s National Theatre is spotlighting recordings of plays from its archives which are being streamed for free on a weekly basis. Elsewhere, the Serpentine was quick to respond to the closure of galleries with an online Twitch stream of a video installation by Jakob Kudsk Steensen.

While size doesn’t always matter, it does seem to come into play when looking at cultural responses to lockdowns. Most of the major museums and art institutions are releasing content that sits in one of two strands: digital programmes (which often repurpose material from past or recent exhibitions) and virtual tours of their permanent collections. These tours are by and large making use of Google Arts and Culture or Google Street View technology, and many have already been available for several years. While nice to have, the tours deliver a slightly lacklustre, superficial result compared to the real experience.

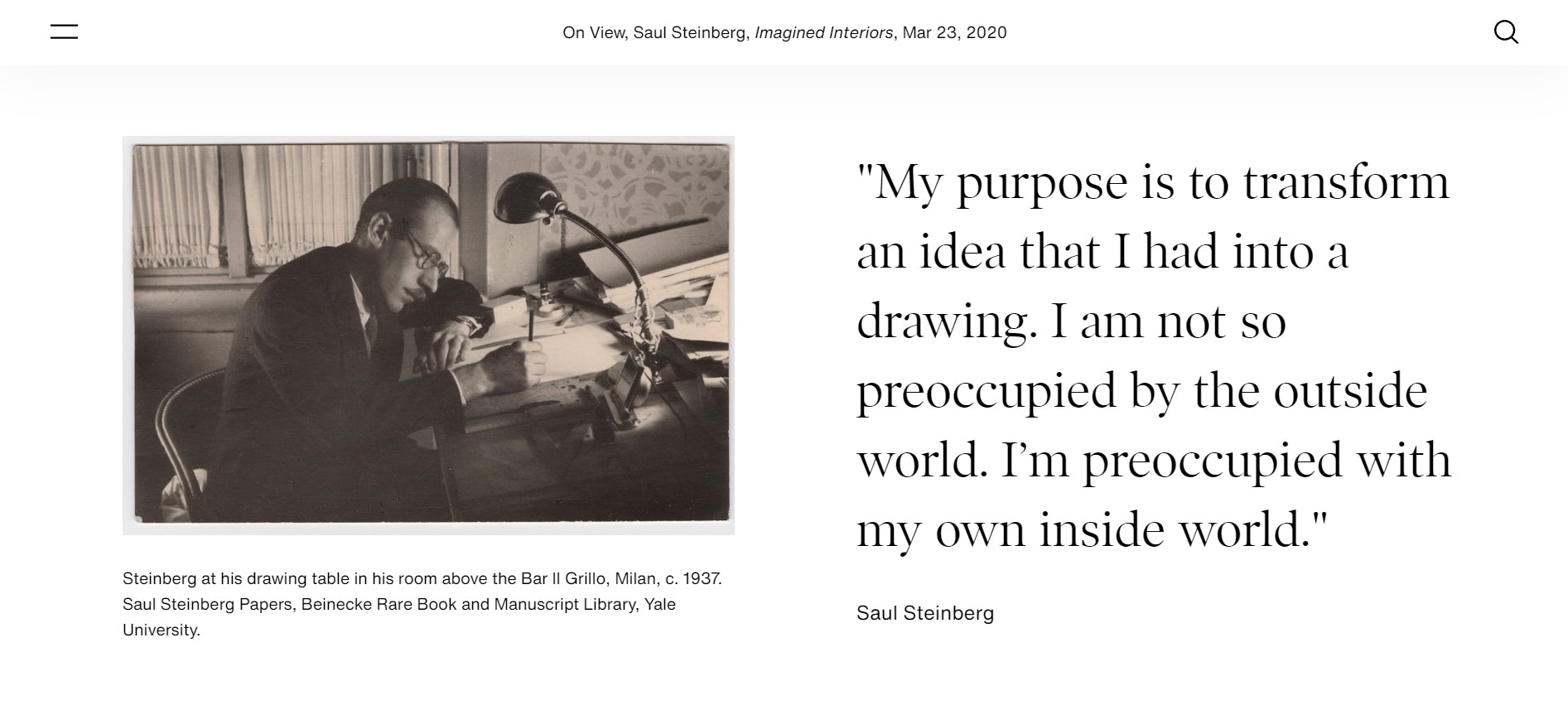

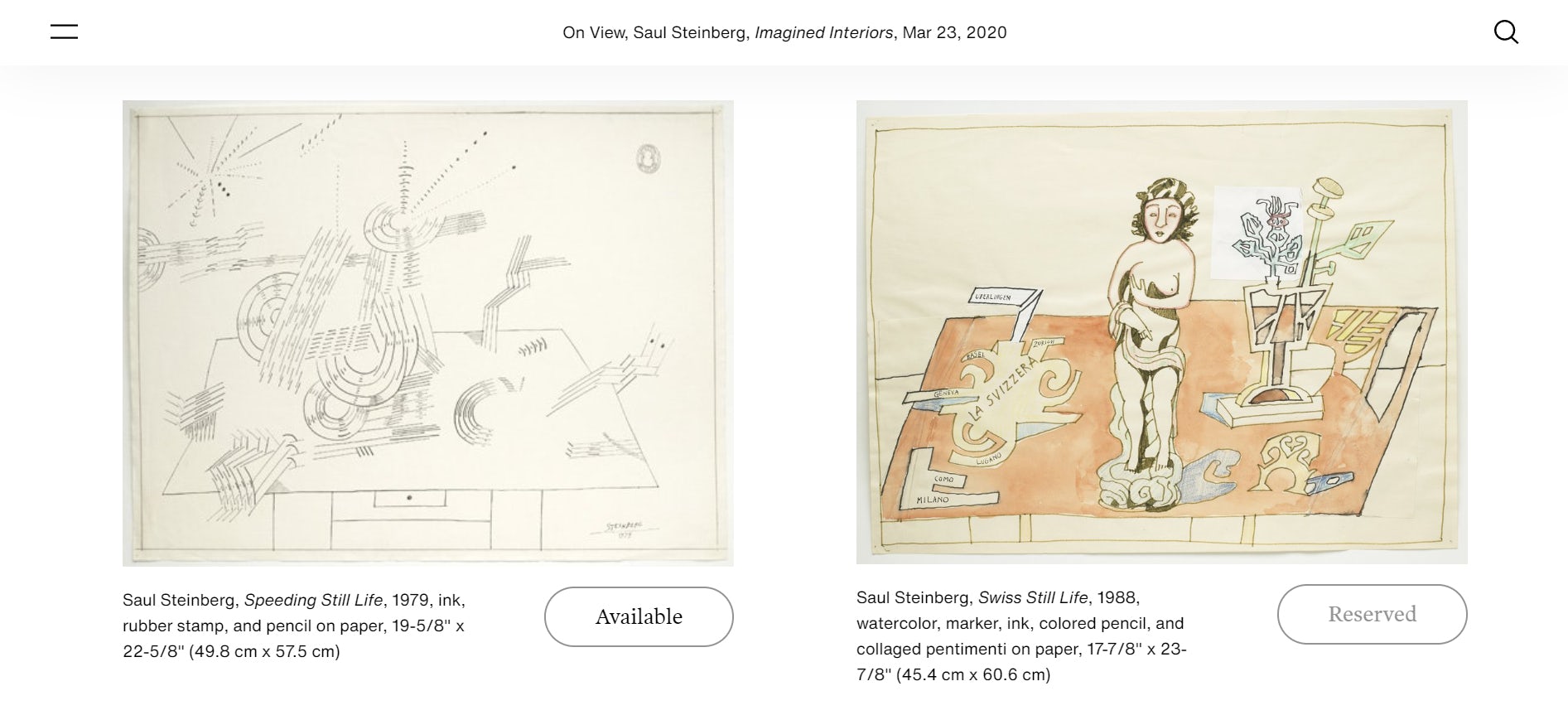

Other galleries are using simple text-image layouts to share their works, similar to the format seen in Art Basel’s Online Viewing Rooms. Of course, translating a blockbuster exhibition to an interactive environment in under two weeks is hardly something we can expect of institutions, which are often already under immense strain where resources are concerned. However, it does appear that being ‘bigger’ is more of a hindrance than a help in terms of creating a novel experience amid lockdowns. A small but agile team – one that’s free of institutional bureaucracy, and probably already well acquainted with sudden changes and flexible working – seems to be better equipped in these circumstances.

“We’re a small team at Headlong, and we’re very nimble, and there’s a real attitude of saying yes to things. It was just a back-of-a-napkin idea that I had about a week and a half ago, and Jeremy just backed it, and now we’re doing it and it’s really exciting,” Race Roughan says. “We’ve got the skillset and the sort of agility as a company to move quickly on things – and also we’re making it up as we go along, as obviously we’ve never done this.”

The global pandemic has brought about seismic changes across the cultural landscape, changing how we interact with one another, how we choose to spend our (great deal of) spare time, and who we’re happy to support. It’s also ushered in questions around whether pivoting to virtual activities could be the way forward regardless, particularly when considering travel in relation to the climate crisis.

Spiegler expects more movement towards online activities moving forward. “We are increasingly seeing digital platforms becoming more important for collectors, galleries and artists alike and we strongly want to support this growth. Especially in recent months, digitalisation has proven hugely important in making art accessible despite restrictions on movement and travel,” he says. He’s also believes that, as far as art buying is concerned, taking advantage of digital platforms should level the playing field from a geographical and financial point of view. That goes for buyers and artists alike, noting that the Online Viewing Rooms offers more “price transparency than at the fairs” (all the online artworks came with a price or price range) and hopes that they “will generate activity for them from around the globe”.

There’s something very freeing about having to innovate process as well as innovate product

Geographical limitations are being considered at Headlong, too. Many of the emerging directors on its Origins Artists scheme are based all around the UK, while Headlong – and much of theatreland – is headquartered in London. Current circumstances have given the team food for thought: having recently adopted Zoom for remote team meetings, they realised that it was an effective way of supporting its UK-wide roster of directors. “I just suddenly thought: we should have been doing this all year. This is such an obvious, easy way to check in,” Race Roughan says.

As for long-term changes, the Headlong team are still working that out. “What the future of digital plays is, I don’t know yet – I think we won’t know until we’ve done it,” Race Roughan says. “I was reading a Guardian article [about how] in Russia they’re starting to do plays for an audience of one, and I just thought, that is completely brilliant!” she laughs. “There’s a digital response and also a non-digital response to what’s going on, and it all feels to play for at the moment. The legacy of that will be [determined by] seeing how successful the work is, and I guess how interested the audiences are in it.”

For Art Basel, Spiegler notes a positive outcome from the Online Viewing Rooms. “We’ve received very strong feedback from collectors across the globe, commenting on the strong quality of the 2,000-plus artworks available to explore in one digital space,” he says. There has been some scepticism about how small and medium-sized galleries will fare under these conditions. With sales often split between buying at the art fairs and ‘off-floor’ (i.e. private) selling finalised through galleries’ own platforms, smaller galleries with fewer resources may struggle to make an impact through their own less advanced websites.

However, with over 250,000 visitors using the platform during the week of the fair, there are undoubtedly benefits even for smaller galleries. Spiegler highlights that the Online Viewing Rooms have offered the opportunity to “connect … with new potential clients from around the world – which is especially important today. This initiative also generated serious and qualified leads and connections, as well as strong sales for some galleries. Overall, it was important for us in this challenging time to provide an alternative platform for the art world to engage and stay connected.”

A challenging time indeed – but Race Roughan is trying to see the upside. “It feels like a proper challenge. A lot of us have been making theatre in the same structure, the same time structure for a long time. We’re used to four weeks’ rehearsal, technical rehearsal, dress rehearsal, preview, press night. There’s something very freeing about having to innovate process as well as innovate product,” she says. “I think the joy of this is heading with a group of incredible artists into completely uncharted territory, and saying we get to reinvent how the hell you make theatre.”