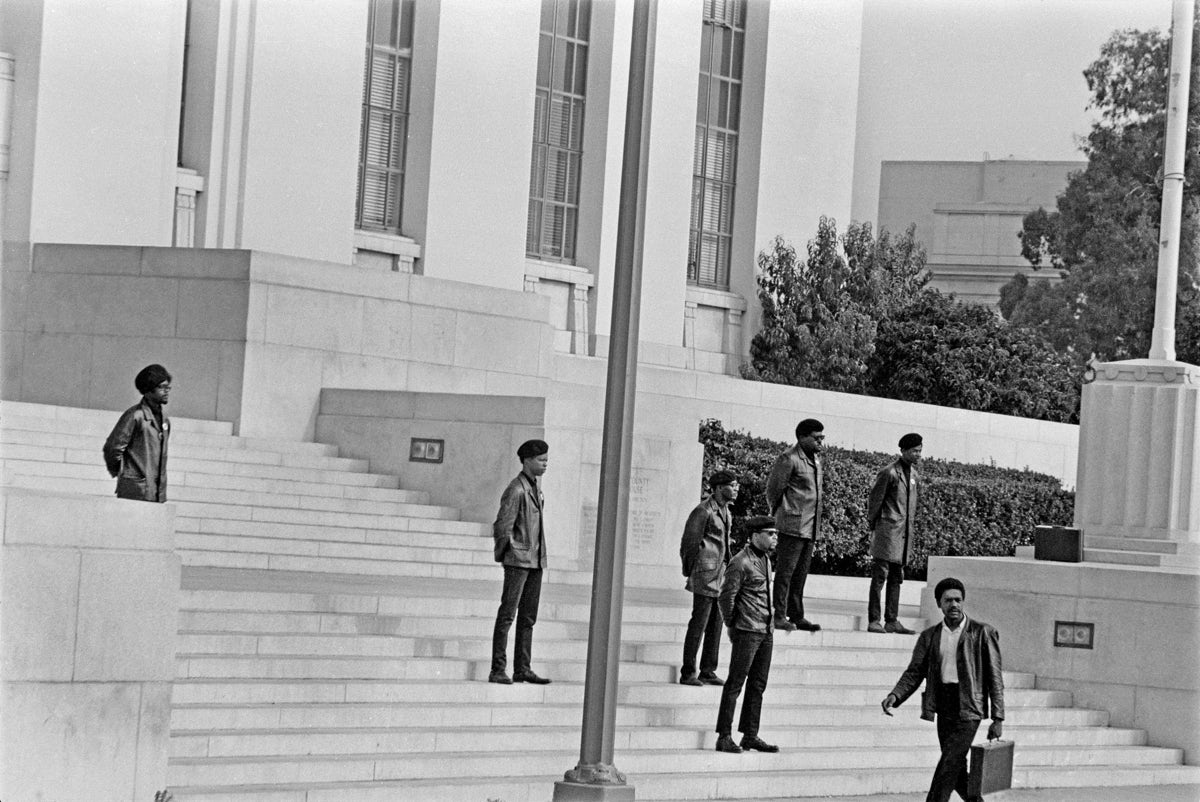

Photographing the Black Panthers

New York Times photography editor Jeffrey Henson Scales and ‘unofficial’ Panthers photographer Stephen Shames share the stories behind a pair of new photo books dedicated to the political organisation

Photographer Jeffrey Henson Scales started taking pictures of the Black Panthers when he was just 14. Having grown up poring over copies of “big picture magazines” such as Life, or Look, and with an at-home darkroom and a pair of creative parents, it seems inevitable that he’d get behind a camera eventually.

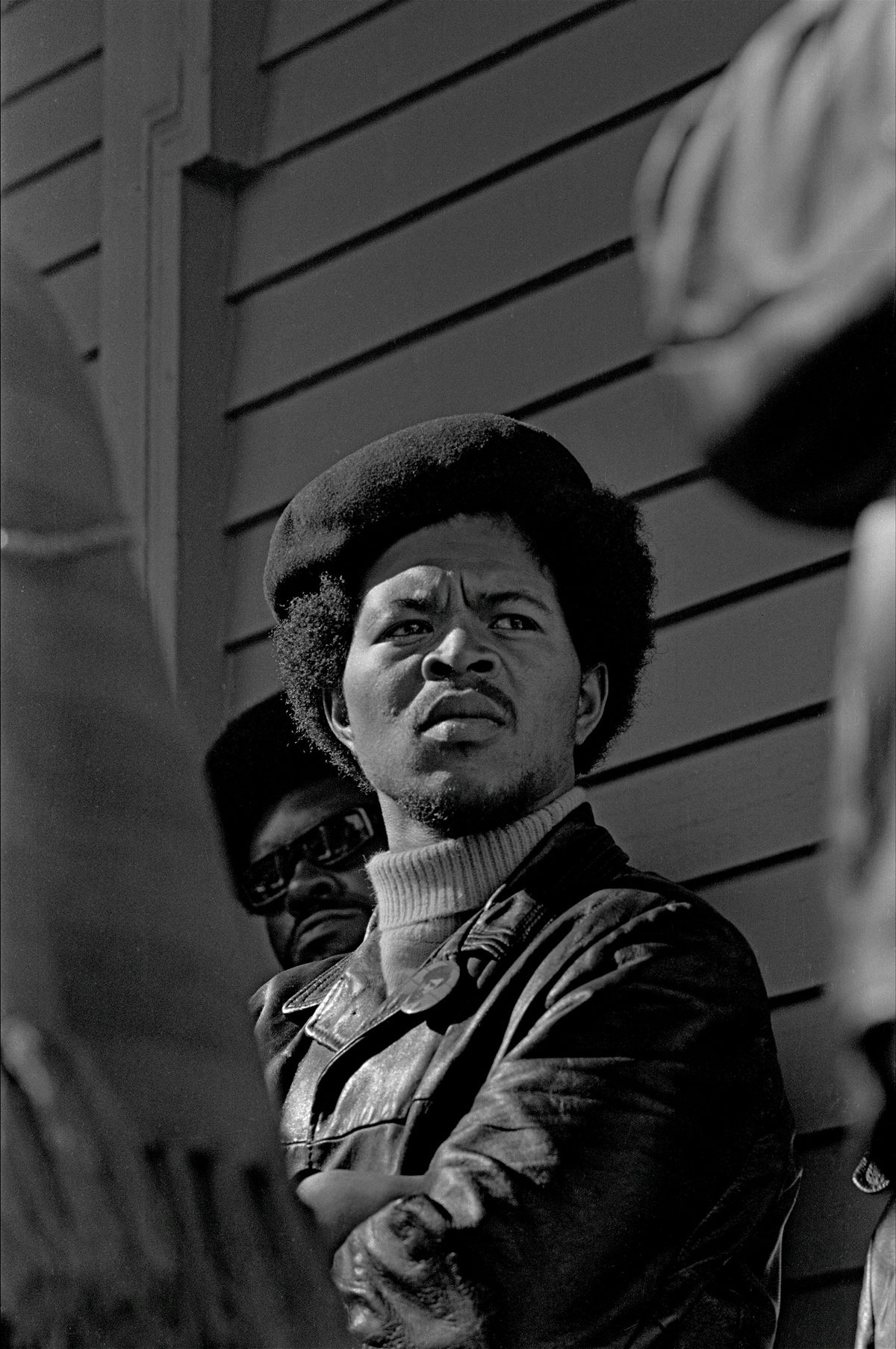

Scales, who now works as a photography editor at the New York Times, spent his childhood in the San Francisco Bay Area, first in the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood, and then the city of Berkeley on the other side of the bay. “The Panthers were people that were around my parents, because my father was a bit of an activist, and would do fundraisers for political organisations,” Scales tells CR, adding that this meant their house was often under FBI surveillance. “These were the sort of people that were in my world. They were around and they were exciting. It was very exciting visually, and it was an exciting time in America.”

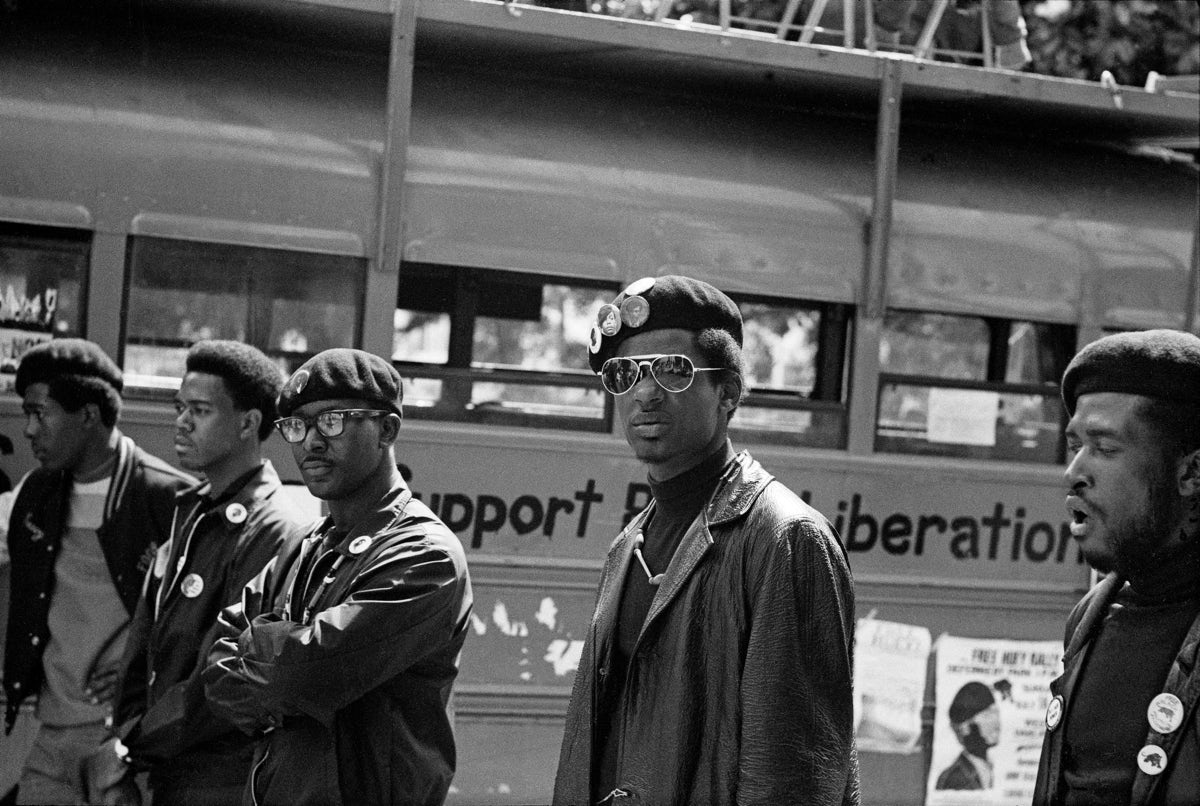

The Black Panthers, originally established as the Black Panther Party for Self Defence, were founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, with the aim of ending police brutality against Black people as well as advocating for armed self-defence. The mission expanded over time, with the political organisation setting up various social programmes including providing free breakfast to children. J Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI at the time, famously described the Panthers as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”, with the FBI presiding over a major counter-intelligence programme to undermine the party.

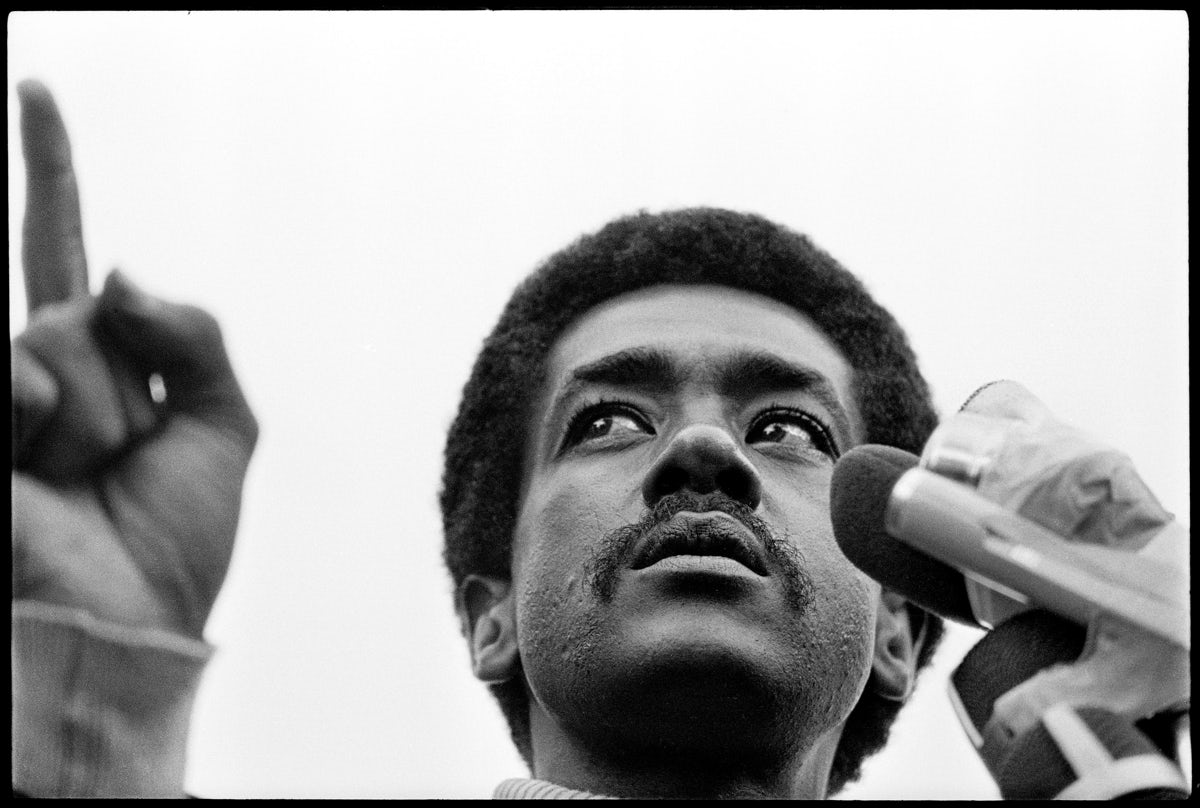

Scales – whose images are collected together in a new photo book entitled In A Time of Panthers: Early Photographs – frames his experience documenting a heady time in American history as “pretty instinctive”. “[The Panthers] really were addressing issues of the time like nobody else was at that particular time,” he says. “It was really exciting – sort of like news unfolding in front of you. For a variety of reasons, the leadership gave me a lot of access, and it’s great as a developing photographer to be in a situation where there’s something dramatic to photograph.”

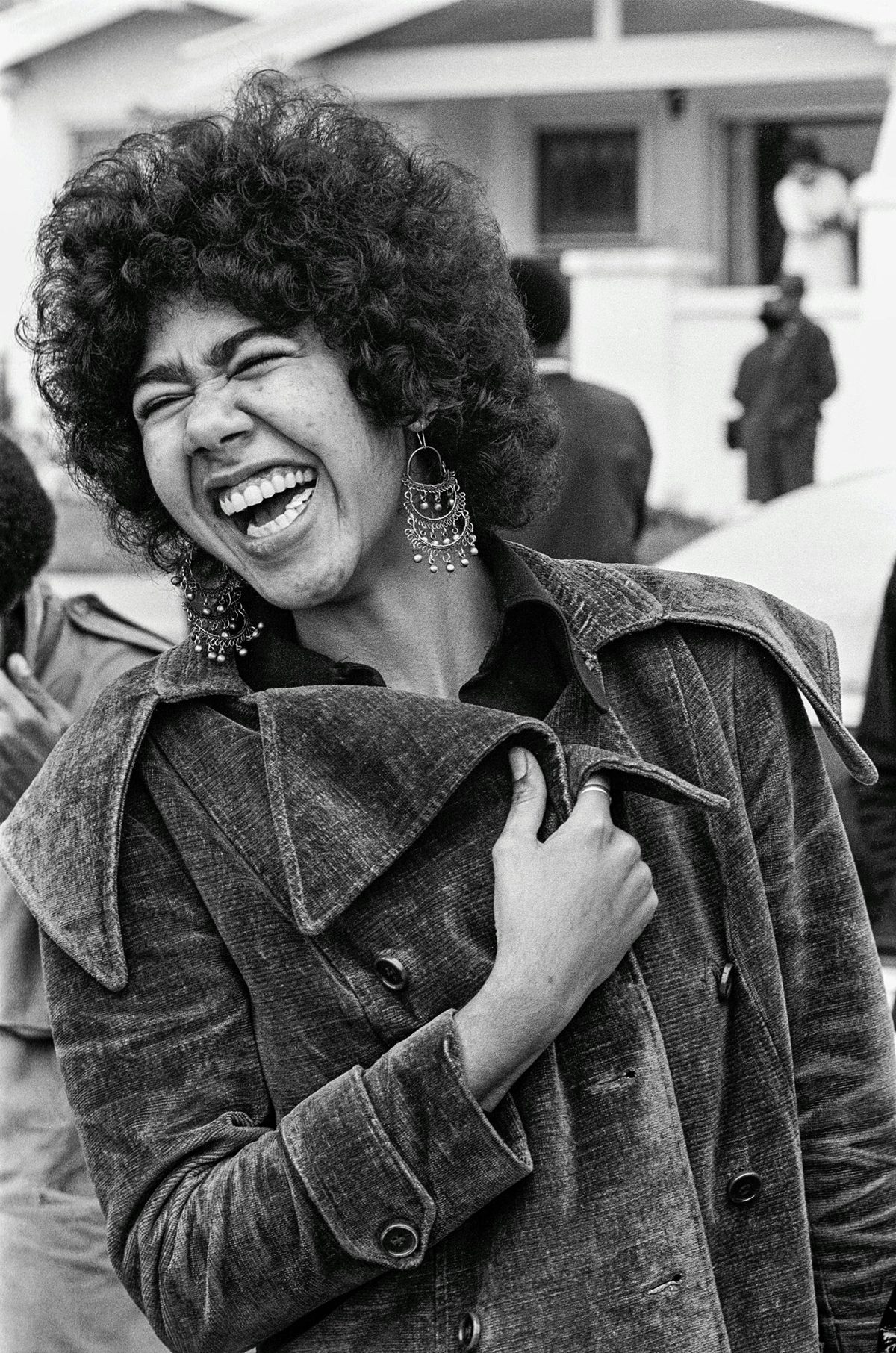

Photojournalist Stephen Shames has also recently published a photo book dedicated to the organisation, entitled Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party, which draws on his experience as an “unofficial photographer” – a role he assumed as a 20-year-old student at the University of California in Berkeley.

“The Panthers were always hanging around the campus and at rallies, so I went by their office and showed them some of my pictures,” he explains. “Bobby [Seale, the organisation co-founder] liked my pictures, and they started using them in the newspaper … I was able to go behind the scenes, not just at the rallies, and was granted incredible access that nobody else ever had … very few people were in their homes, in the Panthers’ school, or able to go into the backrooms of the office.”

Shames says this is the first photo book dedicated to the women of the party, who he describes as playing a significant role which, like many other movements, has often gone unrecognised. “I was photographing the Panthers before Ms magazine and the women’s movement,” he tells CR. “The Panthers were a male-oriented group, but what I’ll say is that in terms of women’s issues, and also gay issues, the Panthers were way ahead of everybody else.”

The photojournalist has now completed three Panthers photo books – which is a far cry from the 1970s, when his plans to release an official Panthers book with founder Huey Newton were dashed. According to Shames, then-president Richard Nixon and vice president Spiro Agnew put pressure on the publisher to abandon the project, and they ultimately fired the editor who’d suggested it. “Sometimes, when 40 or 50 years pass and people look back, history looks different,” he says, of the change in attitude. “It’s depoliticised in the sense that back then the government was really out to destroy the Panthers.”

Shames also believes the public’s fascination with these images speaks to the innate power of photography – particularly pictures taken pre-AI. “I think in the future people might not believe photographs as much,” he says. “But seeing is believing, and that’s why advertising and film is so powerful. It gets directly into our brain and beyond our consciousness when we see these images, and that’s why they are so important.

“In my photography, and you see it in the book also, I’ve always tried to get behind the scenes and show positive images of Black people and Black families and Black men and women. I think media is very important and the Panthers recognised that, and that’s one of the reasons they wanted me to be the photographer and gave me access. I think Huey [Newton] and Bobby [Seale] and Kathleen Cleaver [civil rights activist and former Panthers member] and Emory Douglas [member and graphic artist] and the other Panthers leaders all recognised that the visual image was very important.”

Scales ascribes a certain poignancy to his images of the Panthers – not least because the rolls of film were missing for 50 years before being rediscovered at the back of a file cabinet at his late mother’s house.

“It was very strange,” he tells CR. “A very strange experience having to go back and relive being a 14 year-old – and particularly, after being a photography editor for so many years and a professional photographer for so many years, because when I was a teenager I wouldn’t say I was really editing. I never did contact sheets, I would just look at the film and say, ‘Oh, I like that one’ and print it up, and the Panthers would put it in their newspaper. I never really edited or thought too much about it, other than it was exciting, I was a teenage activist, I was involved in protest, and we all thought we were going to change the world in the 60s.”

What is clear from both photo books is how critical photography is in terms of documenting and preserving social movements – something CR has written about in relation to recent protests in the UK. As Scales points out, it’s an eminently accessible medium that offers an immediacy that can’t be replicated with the written word.

“Photography’s uniquely attached to history, because it’s probably one of the greatest artistic mediums for describing history,” he says. “People are drawn to photographs of another period of time where there was significant drama happening … going back to the 60s, it was this very dramatic organisation that was aggressively trying to curtail [violence against Black people], and that is really interesting for people in light of what’s happened in America in the last few years.

“The 60s were a very significant period of time in the United States with the civil rights movement, and in many ways the Panthers were the sort of zenith of that time and period … people look at photographs to look at history and almost touch it, because of the reality of photography and the way it describes the actual world.

“Being an educator too, I hope young people look at it and think, ‘well, you can do things that have relevance’,” adds Scales. “It’s not all selfies and filters.”

In A Time of Panthers: Early Photographs by Jeffrey Henson Scales is published by Powerhouse Books, powerhousebooks.com; Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party by Stephen Shames is published by ACC Art Books, accartbooks.com