Inside the mind of Nadav Kander

As Nadav Kander’s new exhibition opens in London, the renowned photographer talks to Gem Fletcher about his process, collaborations and the meaning of art

Photographer and artist Nadav Kander is best known for his haunting portraiture and large-format landscape photographs. His work has long grappled with the human condition, pushing the photographic form to its limits to capture the ineffable sensations of being alive.

In After Dark, his latest exhibition at Flowers Gallery in London, Kander presents three bodies of work: Dark Line – The Thames Estuary, Colour Fields and Treow. In Dark Line, Kander turns his lens to the slow-moving, dark waters of the river Thames as it meets the sea. Drawn to the landscape for its vast horizons and layered histories, he treats the river as a metaphor for perpetual cycles of ending and renewal, contemplating the weight of London’s past, its waters bearing witness to countless generations who have voyaged, fought, traded, loved, lived and died on its banks.

“I’ve been visiting the Thames Estuary since about 2015,” Kander tells me when I ask where his relationship to the river began. “I’m particularly drawn to water, especially slow-moving water. I love the metaphor of the river ending, the journey slows down and widens, ready to join the sea and be absorbed into a greater whole. It’s almost exhausted by the weight of London’s history it has carried.”

The ongoing series was informed by Charles Dickens, who used the river as a metaphor for the underworld. “In those days, there used to be people employed to fish bodies out of the river because it was such a site of suicide, killings and getting rid of things,” says Kander. “It’s an amazingly beautiful, dark place. Human toil, for some reason, can be very beautiful.”

Making poetry out of collisions has long been the purview of Kander’s practice: to forge from familiar elements something strange, to hide and reveal, to light up and darken, to blur the lines between the beautiful and the vulgar. Kander is quick to assert that the viewer is critical to the success of the work.

I want to create a feeling in a photograph. I judge how I feel about a work of art, if I feel something. If there is more to the work than what I’m looking at

Like painting, photography relies on fragments of personal experience from the viewer as a way of teasing out the fantastical in any given piece. In truth, photography’s mechanisms are deceptively simple, and yet it has the capacity to conjure complex and even contradictory messages and feelings, which is what makes the medium so fascinating.

“I want to create a feeling in a photograph,” explains Kander. “When I think about abstract painting, such as Rothko, it’s fascinating how much you can sense in the atmosphere of the work. I’m interested in the optical unconscious and how what you can’t see can come into view or become known. I judge how I feel about a work of art, if I feel something. If there is more to the work than what I’m looking at.”

In After Dark, this sentiment is most potent in Kander’s Colour Field images. The viewer looks on to three mysterious landscapes — including the Atlantic Ocean shot from Copacabana Beach, and a barren vista by a Ford dealership in Indiana — that fall into blackness. Playing with the concept of abstraction, Kander brings forward planes of colour and texture, presenting views that cannot exist naturally. As he puts it, “These are manmade views lit by manmade light.” The result is an uncanny and uncomfortable reminder of the instability of our planet and what it feels like to be alive.

“I use blackness as a metaphor for not knowing,” he tells me. “If one can be okay with not knowing, then it can be full of potential. I’ve been thinking a lot about darkness and Greek myth recently, and reading about the goddess Nyx. Not only is she very powerful — she’s the only goddess who can challenge Zeus — but she’s born out of the chaos of day. I find that really beautiful, born out of chaos, into darkness.”

While Kander’s work pulls on a constellation of references and personal experiences, his process remains mysterious, even to him. “I’m a bit scared in a way, to really fully understand or discover how I do what I do. When I start a project, it’s often a clean slate; it’s about following a whim, like going to the river and seeing what comes up.”

In addition to his art practice, Kander remains active and intentional with editorial and commercial assignments, taking pleasure in both the process and the challenge to create a deeper emotional connection in images, which by their nature are transient. “Creating my own work can feel incredibly insular and introspective, so I really enjoy collaboration on editorial projects and getting into a flow with a group and coming up with something better than I would have on my own.”

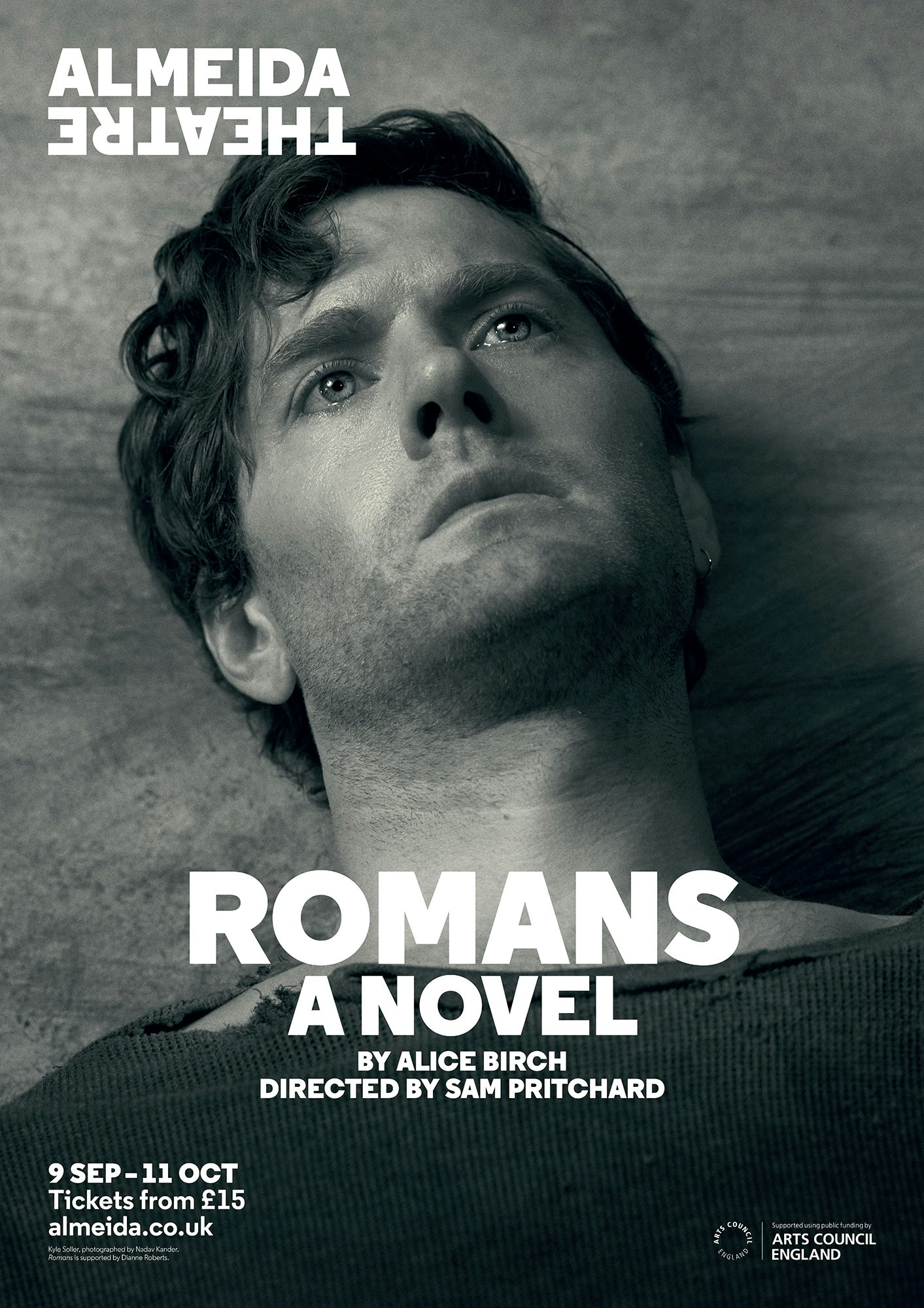

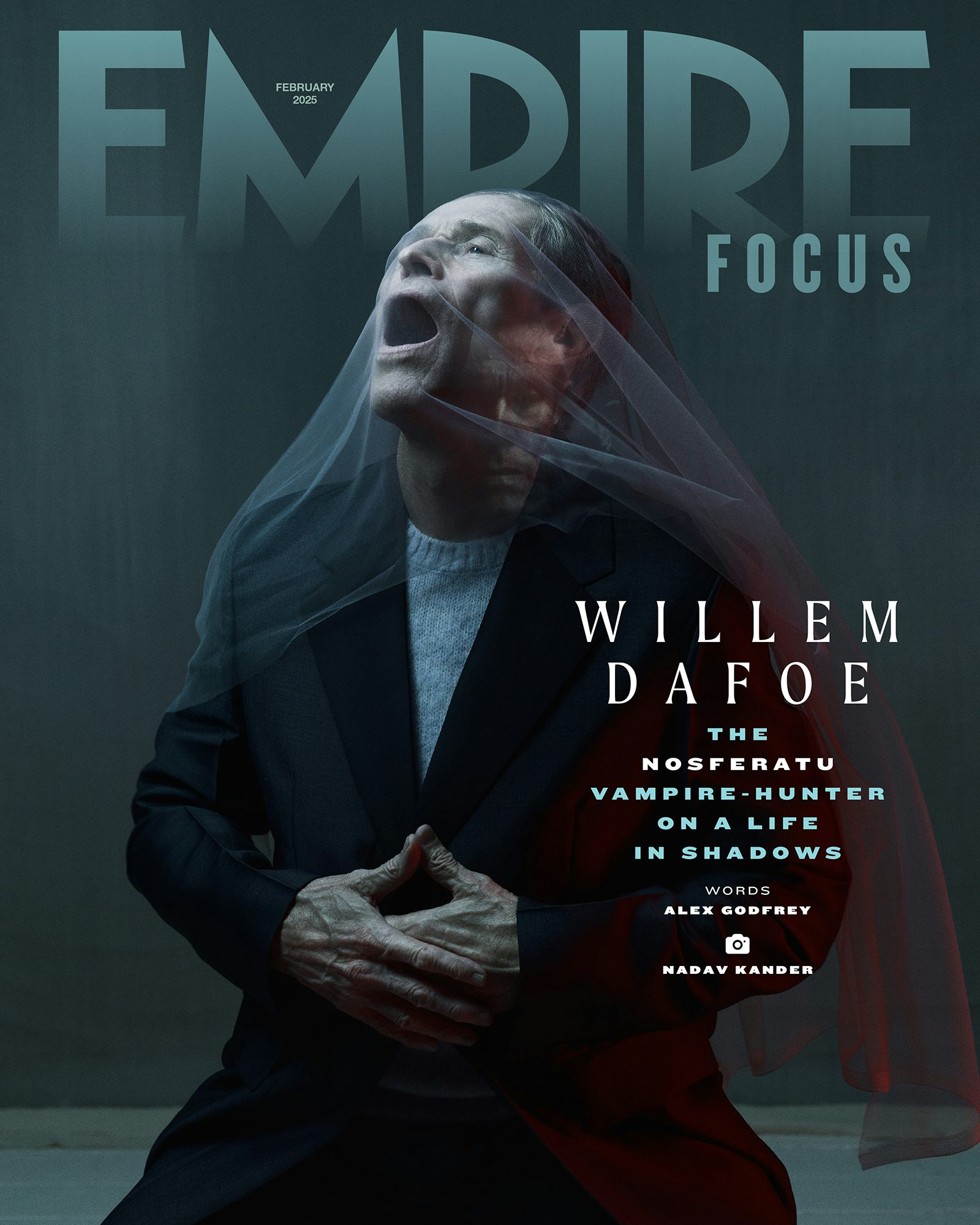

While Kander remains open to collaborations, he has developed a niche in the worlds of fashion and performance that offers him a way to explore ideas and approaches honed in his personal work. These adjacencies — felt in recent work for Paramount, Empire Magazine, The Old Vic, Sky, The Young Vic, Balenciaga, Fear of God and Document Journal — offer a potent reminder that commissioned photography (which currently feels at an all-time low in terms of innovation) has the potential to do more than clog up our feeds. Done well, it can stop you in your tracks.

I really enjoy collaboration on editorial projects and getting into a flow with a group and coming up with something better than I would have on my own

“I’m not deep in the fashion world, but it’s an area where people most understand this desire for feeling,” explains Kander, who has recently created three campaigns for renowned LA Streetwear brand Fear of God. “When I worked with Jerry [Lorenzo at Fear of God], he wanted emotion. What could be a better brief?”

Kander also has a long relationship with London’s Almeida theatre, a collaboration he holds dear. “It’s about building intrigue with the Almeida, not giving it all away. There is real nuance in that process. Although my subject matter can be incredibly varied, my pursuit is the same. Whether it’s a portrait or a piece of water, it doesn’t matter.”

Interestingly, it was an editorial shoot with Ian McEwen which became formative for Kander way beyond the time they shared. “Editorial obviously doesn’t pay much, but it does give me access to people like Ian, who, in a way, changed my life. I was photographing him, and he’s not that easy to photograph. It wasn’t working, and he could feel it. He put his hands down and just said, ‘Nadav, what is it that you pursue?’ and I’ve been trying to answer him ever since.”

Now, several decades into his career, and in a world in which the future feels unpredictable, Kander is reflective about what the work of art is. “I really struggle with it at the moment,” he shares. “We are in a time that seems to be very needy of artists to produce things that don’t challenge so much as try to move us to the next paradigm of living on this planet.

“If people can stand in front of your work and feel they could have a changing relationship with the picture, then, in a way, you are doing your work. You are bringing them into a more abstract world where they can understand themselves better. That’s the work of art. Is that appropriate enough in these times? I don’t know.”

Nadav Kander: After Dark is at Flowers Gallery in London until October 11; nadavkander.com