Exposure: Ramona Jingru Wang

Based “between New York and the internet”, photographer Ramona Jingru Wang’s work is inspired by a life spent online. She talks to Gem Fletcher about her process

While the internet is responsible for the ubiquity of photography, digital culture’s visual codes and challenging format restrictions have, over time, siloed the photograph from the cultural discourse, pushing a once dominant medium down the value chain.

Photographer Ramona Jingru Wang, who describes herself as being based “between New York and the internet”, has been conscious of these shifts from the moment she picked up a camera. Unlike many of her peers, Wang’s work is entirely intertwined with internet culture: online coded aesthetics, surreal concepts and satirical provocations reflect the varied and chaotic experience of life online.

“When I was in grad school, photography was oriented towards the physical, and how an image is experienced in real life. This felt very outdated to me,” explains Wang. “Focusing only on the physical means the work is only accessible to an immediate circle. The undertone of my practice has always been about reaching and resonating with a lot of people.”

While accessibility is important to Wang, her work is primarily concerned with how images intervene with our reality, how they create connections between people and spaces, and how they can speak to the myriad of pros and cons of our terminally plugged-in existence.

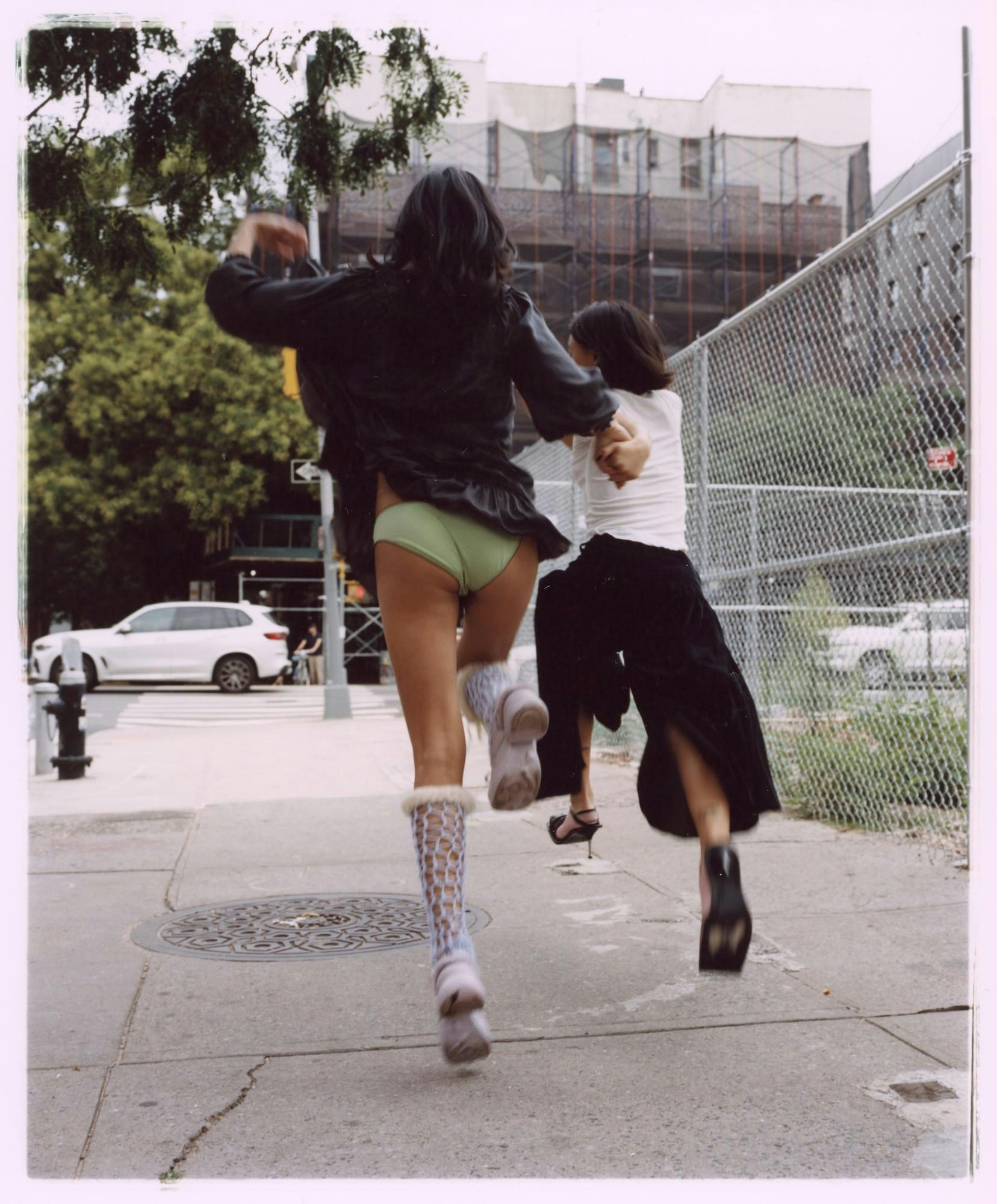

In Poor Image, she collates photographs and gifs shot in Coney Island that explore the slippage between dream and memory, a consequence of our hybrid existence living on- and off-line. Named after Hito Steyerl’s influential essay, In Defence of the Poor Image, Wang’s project reverse-engineers the sensation of memory slippage by blending nostalgic and nonsensical elements with the codes of vernacular photography to evoke the narrative chaos of dream sequences.

I’m interested in the parallels between the notion of being cyborg and being Asian, and how it can be a transcending concept for our current world

“I often forget things that happened, and think my dreams were memories,” explains Wang about the driving force behind the work. “We are always looking at screens and then later trying to figure out if it happened in real life, or was something you saw online. This dissonant feeling is partly why I gravitated towards photography – to keep track of real memories and distinguish them from dreams.”

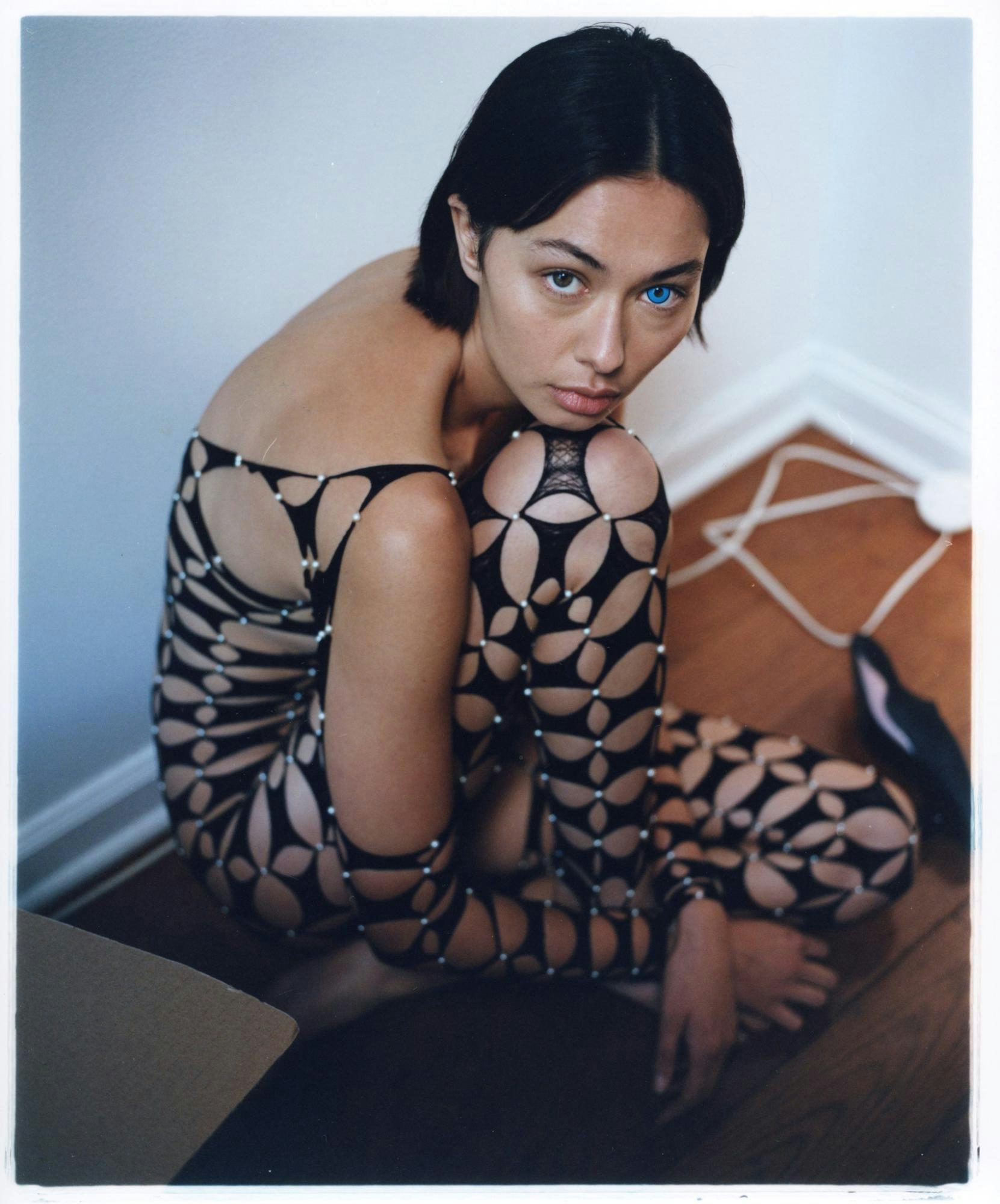

In Wang’s most renowned work, ‘My friends are cyborgs, but that’s okay’, she crafts a mockumentary style series that interrogates the Asian stereotypes that play out in pop culture. Informed by Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism, Wang invited her participants to imagine themselves as outsiders, using their real-life experience of ‘othering’ to inform their performance. The project underscores the danger of such reductive narratives — made more pervasive through the internet — while calling for more nuanced, multi-faceted representations.

“I’m interested in the parallels between the notion of being cyborg and being Asian, and how it can be a transcending concept for our current world, where the societal perceptions of Asian bodies have been, unfortunately, viewed through the dual lens of techno-Orientalism and standard Orientalism,” explains Wang. “With this series, I hope to offer a narrative of an Asian future distinct from the conventional Western techno-dystopian visions.”

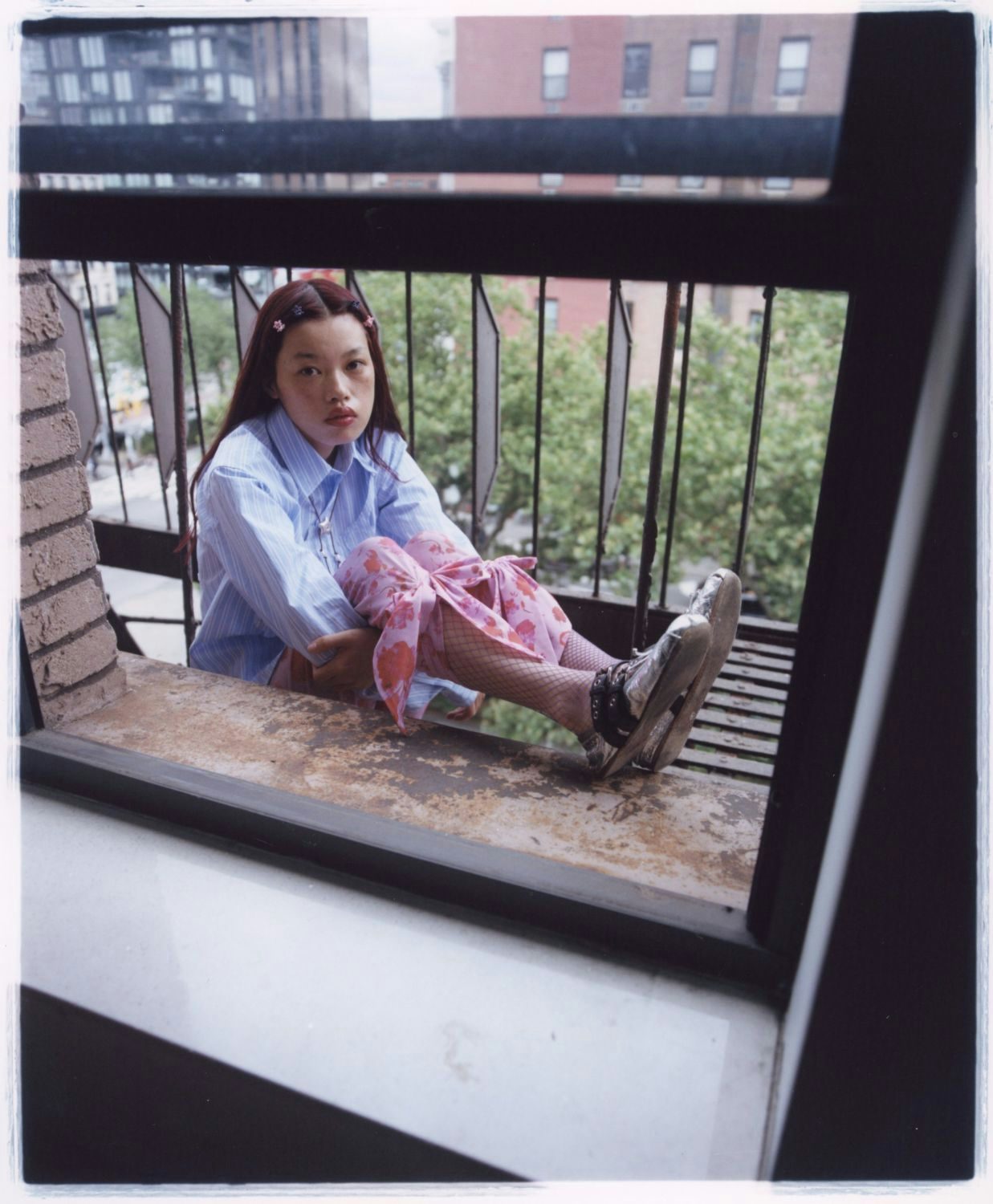

The root of many of Wang’s projects, including her upcoming book, Go See*, are born from her experience modelling and the often reductive ways her ethnicity was defined in castings and campaigns. As a riposte to the fashion industry’s constant flattening of Asian identity to monolithic stereotypes, Go See* illuminates the diverse identities of Asian models, celebrating the richness of their narratives, while recognising their resilience to push back against the industry’s reductive tendencies.

Made in collaboration with creative director and stylist Momoè Sadamatsu, Go See* will be published this autumn by Friend Editions, presenting Wang’s portraits alongside text and ephemera belonging to each model.

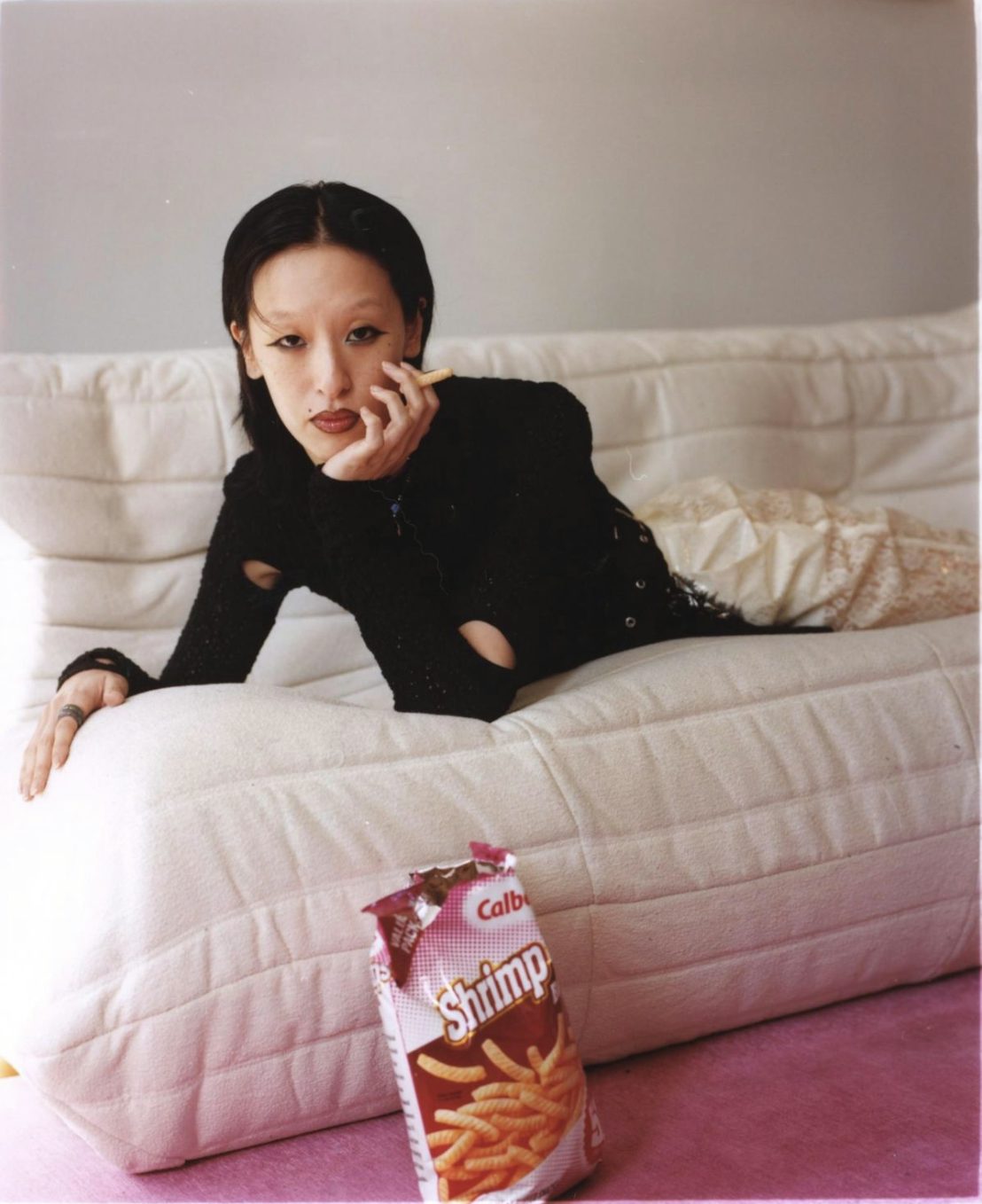

In her latest work, To Be Seen, To Be Held, Wang brings together portraits of women from her evolving archive — traversing personal, commercial and documentary projects that explore the complexities of Asian women’s identity across different spaces.

“As an Asian woman photographing other Asian women, I am constantly negotiating how we are perceived, portrayed, and understood,” Wang explains. “My camera becomes both a mirror and a medium — for affirmation, for care, and sometimes, for refusal. Whether in editorial commissions, quiet portraits, or observational work rooted in family and community, each image asks: What does it mean to be seen on your terms? And what does it take to be held — in history, in culture, in one another’s gaze?”

Throughout Wang’s eclectic practice, we feel the effect that technology has on our everyday lives and the rapid ways the internet and digital culture are reimaging our shared human experience.