A new exhibition confronts the seductive face of fascism

The Future Was Then, which runs at New York’s Poster House, offers a timely look at the enduring power of state-sponsored propaganda

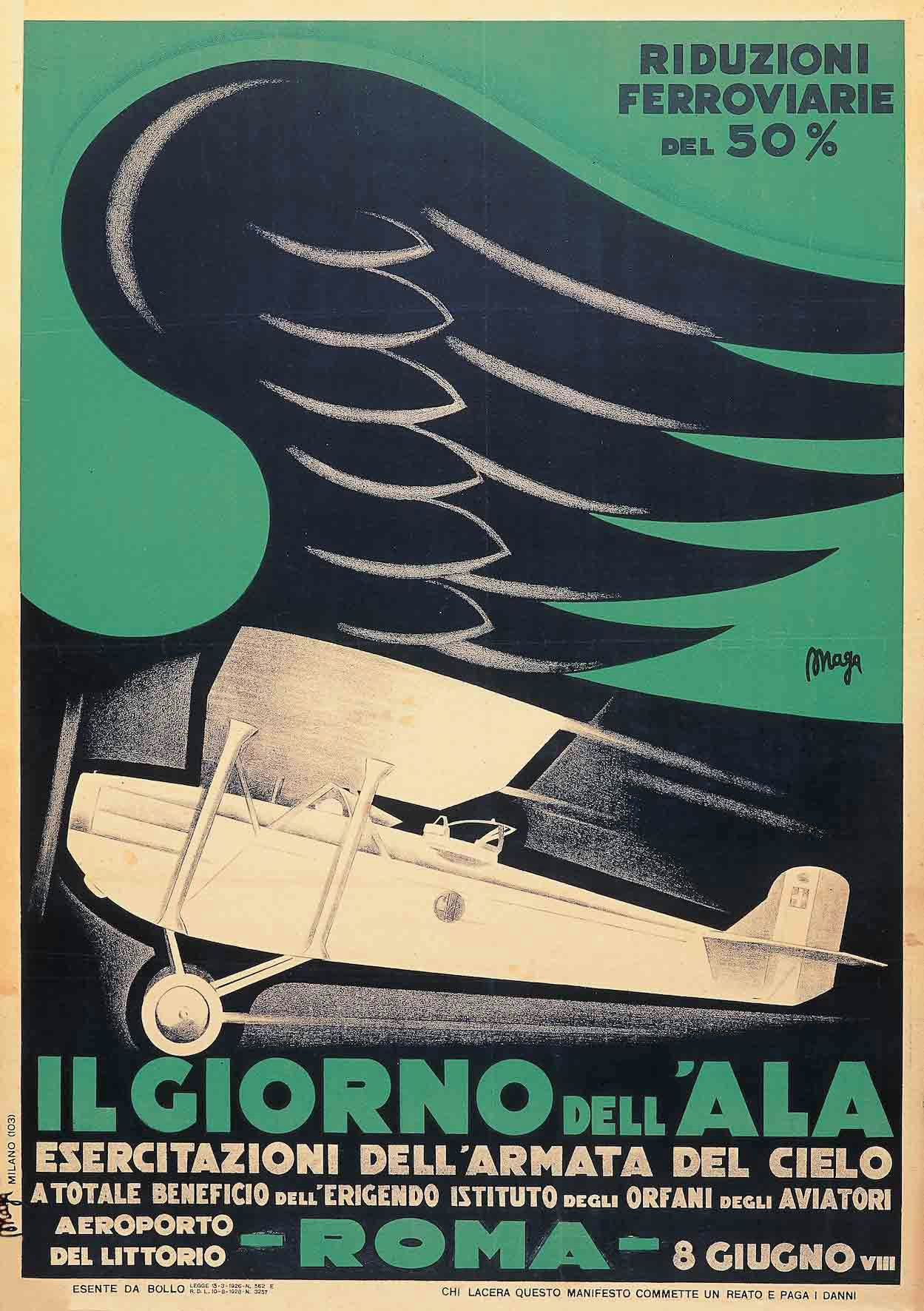

At first glance, the artwork on view in Poster House’s latest exhibition is dazzling – sleek planes, swooping eagles, heroic figures rendered in bold colours and modernist forms. But beneath this elegant façade lies a darker story of coercion and control.

Running in New York until February next year, The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy traces how Benito Mussolini’s regime enlisted artists and advertisers to craft a national brand, projecting an image of both domestic pride and international prestige.

Curated by photographic artist and author BA Van Sise, the show brings together more than 75 works on loan from Bologna’s Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli. From avant-garde photomontages to consumer product posters, it maps how creativity and propaganda fused in Mussolini’s Italy – a nation struggling to transform itself from what he saw as a “third world country” into a modern global power.

“The Cirulli collection is massive – an absolute treasure trove of history,” Van Sise says. “The core of the selection relates to the narrative of who Italy was at that time. Mussolini’s efforts begin with selling Italy itself: to foreign powers, but also to Italians. The throughline of the show is absolutely this: how do Mussolini’s goals of selling Italy permeate the sense of selling in Italy and selling by Italy?”

That marketing strategy is on full display in highlights such as Xanti Schawinsky’s Sì (1934), Paolo Federico Garretto’s Camicia Nera (1933) and Giovanni Minguzzi’s Giornata dell’Ala (1933). Posters promoting Fiat cars or national fairs echo the aesthetics of state-sponsored propaganda, reinforcing autocratic ideals where, as Van Sise puts it, “Italian companies are Italian, Italians are Italians, and Italians should take pride in themselves because of their corporate grandeur.”

Van Sise believes the appeal of these posters poses a challenge for contemporary audiences. “There’s no absence of artistic talent in any system of government,” he says. “What made the fascist regimes of the 1930s so remarkable is that, viewed with modern eyes, there’s an innate sense of style. In Italy, artists and poets were at the heart of Mussolini’s movement. The important thing was to provide the contrast of reality: yes, there’s an empire, but at what cost? Yes, we have certain materials, but where do they come from?”

For Van Sise, curating this exhibition was at once a professional duty and a personal obligation. So how, on both levels, does he reconcile the artistic brilliance and inherent political violence of the work? “On a professional level, it’s easy: artistic innovation comes from everywhere. Mussolini’s propaganda was fairly easy to fall for, and it’s easy to understand why so many Italians did – he was, in many but not all ways, successful.

“On a personal level, it’s tougher. My grandfather escaped Italy on the Rex – whose poster is in our show – and later was in the mob that hanged Mussolini. My grandmother and her brothers spent the war hiding in a church basement. I knew these people. I carry their blood in me and their faces on me. I’m just glad that in two generations, we’ve gone from hanging him up in city squares to hanging him up in a museum.”

The mechanics of Mussolini’s propaganda, Van Sise warns, continue to reverberate in political communication today. “Modern fascist movements very, very frequently reference 1930s and 40s propaganda – its hopeful workers, its patriotic thugs, its racist tropes. There’s great intentionality to that, and it transcends nation states. The big difference today is the implementation. Back then, artists were seen as essential to the cause. Today, it’s just some artless mouthbreather typing in a prompt on ChatGPT and posting it on Instagram. Same old branding, brand new balderdash.”

By placing this seductive visual language within a critical frame, The Future Was Then invites visitors to confront the uneasy overlap between beauty and brutality. And in doing so, it suggests that objects in the rearview mirror of history are often much closer than they appear.

The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy is on until February 22, 2026; posterhouse.org