The Monthly Interview: Jonathan Zawada

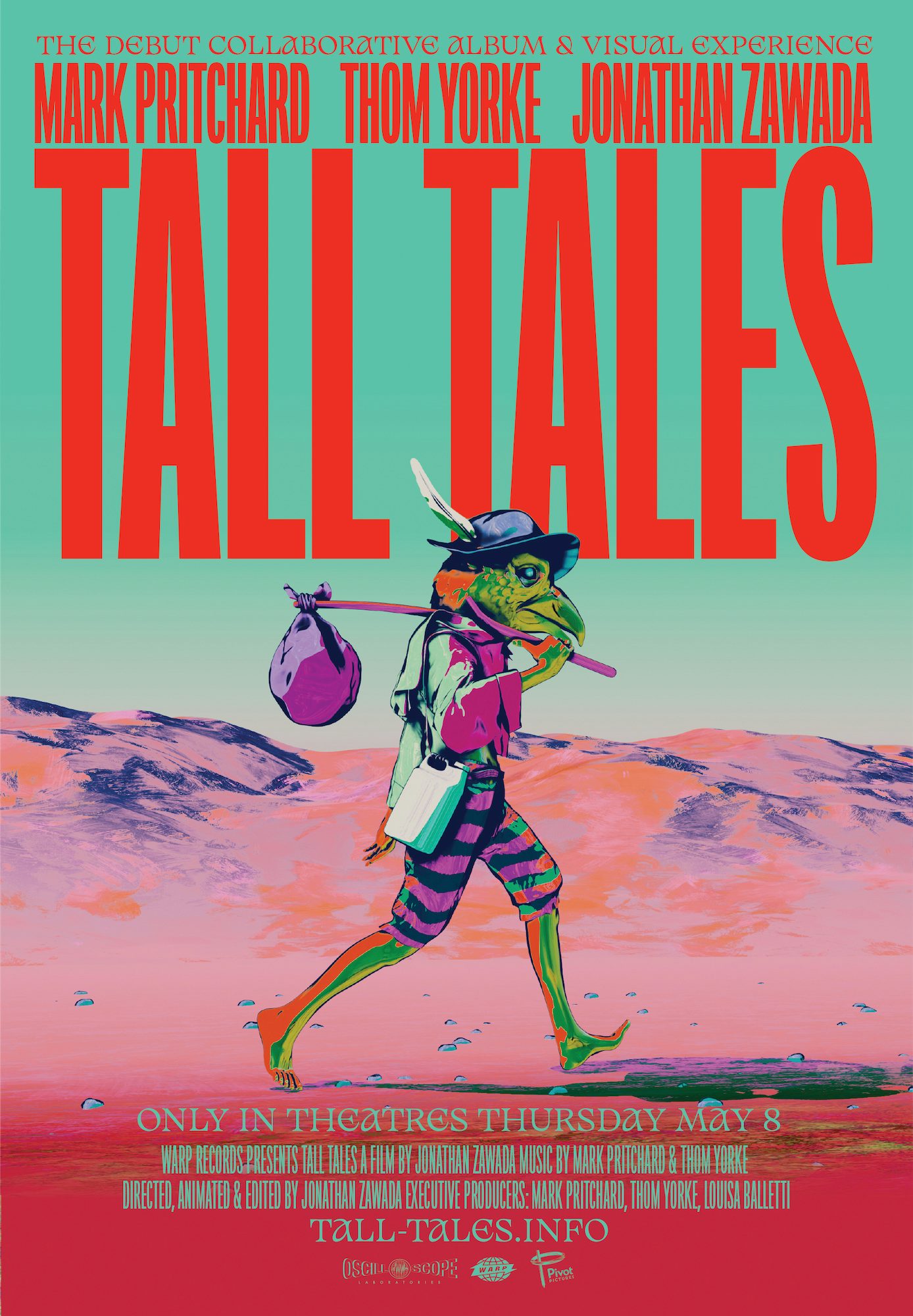

The multi-disciplinary artist has worked with musicians from Flume to The Avalanches and most recently Mark Pritchard and Thom Yorke on their new project, Tall Tales. Here he reflects on the timeless collision of music, art and commerce, plus the influence of AI

Over the past three decades, artist Jonathan Zawada’s work has seen him exploring the complex, inextricable relationship between technology and the human experience. With a practice deeply rooted in web design and coding, his colourful, often hyperreal work blends virtual and physical realms, spanning everything from product design to music videos, album artwork and live visuals.

Zawada’s interest in design began in his mid-teens when he undertook an after school job carrying out clean ups at a local animation company. Self-taught in web coding, by the late 1990s he found himself in demand as a programmer, building animated websites and later abandoned a short-lived art and design degree to focus on web design full time. He went on to design the website for Sydney-based electro duo The Presets, who enlisted him to design their EP cover, sparking a whole new career avenue in the process.

“At that time, I really wanted to do graphic design,” he recalls. “I was in love with album cover art, just as a fan. I wasn’t really even aware it was a job that you could do, and I definitely didn’t think it was a job that I would end up doing. It was just sort of a meandering, organic process.”

Following diversions into art direction for magazines, books and catalogues and work within streetwear fashion and textiles, Zawada assumed the role of creative director at Australian record label Modular. “It was all very messy and mixed up,” he laughs. “Around the age of 30, I started paring back and figuring out exactly what I wanted to do.” In 2011, he made the decision to relocate from Sydney to Los Angeles with a view to distancing himself from the commercial world entirely.

“I specifically said I’m never doing design for music again, because I really didn’t like the way the record industry worked and I didn’t like the way musicians were treated. I didn’t like the way that the relationships worked between the people in the business, so I stopped entirely and just concentrated on painting.”

Turning his attention to exhibition work, Zawada’s solo US debut saw him painting large-scale topographic landscapes derived from graph data. With other projects underway, he soon found himself being courted by electronic musician Harley Streten, better known as Flume, who enlisted him to create artwork for the 2016 album Skin, which saw Zawada creating floral designs using Blender and 3D animation that drew inspiration from his garden. Having encountered indifference to 3D design in his early years of practice, Flume was hugely enthusiastic. Though initially intended as a one-off project, it led to a long-standing creative partnership that continues to this day.

“I had done those flowers as a challenge for myself to see how realistically I could make some,” he recalls. “Harley really liked those, so I changed them a little bit, manipulated them and then made a bunch more and it expanded from there. The next thing I knew, I’d been doing 3D flowers for two years.”

Buoyed by a newfound passion for collaboration, a prolific period of creativity followed with Zawada re-teaming with The Presets and partnering with the likes of Röyksopp, The Avalanches and Coldplay to create visuals and artwork. He returned to rural New South Wales in Australia in 2017 and hasn’t looked back since.

“Who wants to say no to some of these fun, giant opportunities to do something for a massive Coachella stage, or something that will just be fun to do? I’ve never tried it before and I’m always up for trying something that I haven’t done. As it goes on, it sort of expands. At some point you turn around and there are people with the flower, or a logo tattooed on them and you realise that you’re helping to contribute to building a thing. It does feel good.”

I was in love with album cover art, just as a fan. I wasn’t really even aware it was a job that you could do, and I definitely didn’t think it was a job that I would end up doing

His latest project, Tall Tales, is a collaboration with Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke and pioneering electronic musician Mark Pritchard. The result of over five years of remote collaboration which began during the pandemic, it took shape gradually, with Pritchard and Yorke sharing musical sketches, the latter embellishing them with vocals, synths and additional effects.

Zawada had been working with Pritchard for some time, first collaborating on the 2013 EP Ghosts, and was used to being his sounding board. As Tall Tales took shape musically, Zawada began to explore what the project might look like, initially envisioning it as an installation before settling on a feature-length project consisting of vignettes for each of the album’s 12 tracks.

Zawada’s ideas evolved with the music, experimenting with a blend of 3D animation, historical newsreel and stock footage. Happy Days, an unsettling blend of 1940s archival footage from post-blitz Manchester and surreal AI-inflected claymation, was one of the last segments to be finalised. Character-driven sequences, including the marching army of colourful misfits depicted in Back in the Game and the Hieronymous Bosch-inspired inhabitants of Gangsters ranked among the more challenging outputs.

The latter saw Zawada creating characters in Blender before transposing them into the Unreal game engine to arrange environments, lighting and camera movements. Final segment, The Spirit, features visuals of a skeletal figure dancing on a rowing boat and was originally conceived with the idea of working with motion capture and live choreography. Zawada instead opted for a simple animation evocative of a late-90s video game cutscene.

“I sort of bumble my way through character animation, but I’m a bit like a sledgehammer with it,” he muses. “Something like The Spirit, where there’s just this one character on screen dancing in quite a strange way, there’s nothing to hide behind. I wasn’t that sure that I’d be able to pull off quite complex, delicate sort of character movement.”

A modest budget forced Zawada to get creative. When a recce to shoot just one video in Scotland used up a fifth of his allocation, it became apparent that he would have to keep things tight. A self-confessed early adopter of generative AI, Zawada is all too aware of how polarising a tool it remains in the art world, yet its limited usage on Tall Tales afforded a level of efficiency that would otherwise have been impossible to achieve.

“We were going to shoot a thing with Thom and do some VFX,” he explains. “It just didn’t feel right to do that. What we wanted to do was go back to doing something where I made everything, he made all the music, Thom sang all of the lyrics and it was a tight little project, much closer to being an art project. But if AI didn’t exist, there’s no way I could have made this.”

It’s a much more challenging, interesting thing to think of a still image that can summarise 70 minutes of music than videos and all the rest of it

Zawada licenses all of the visual data he uses in his projects prior to feeding it into a local learning model. Nevertheless, he remains conflicted by its wider usage – particularly its implications for junior creatives starting out.

“Just because something’s hard doesn’t mean it’s an excuse or validates it, so I’m very torn,” he concedes. “I think it’s a bad thing from the standpoint of someone that started off with an after school job doing the cleaning of frames in animation. The amount of stuff that can be outsourced to AI, rather than to a junior, is enormous, so there’s a kind of missed opportunity for young people in terms of learning.”

He is also mindful of how its use fits alongside the album’s ideas around art as a whole. “Thematically and conceptually, it’s built into the DNA of the project, independent of what I’ve overlaid on it,” he continues. “Even in the lyrics that Thom’s written, there’s always been a theme about how we value artwork, what that value really means, and to me that’s all a very open question.”

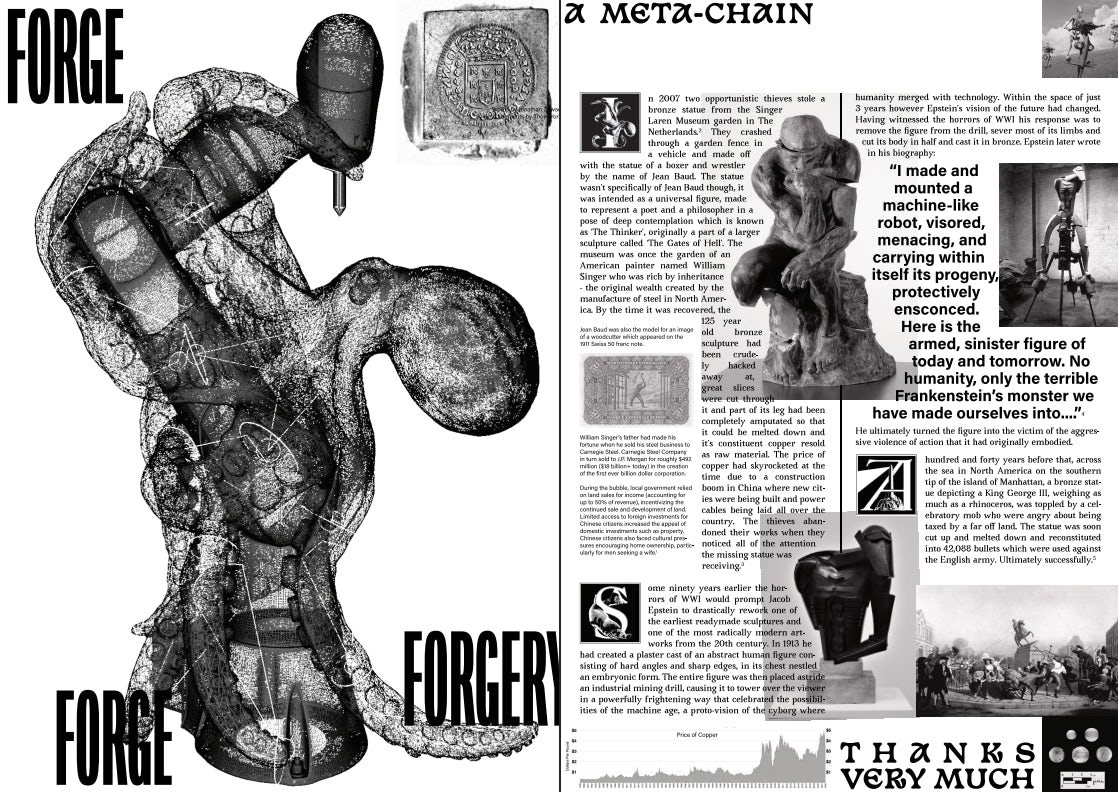

In the latter stages of development, Zawada proposed a bridging device to connect each segment. A longtime fan of video games, he drew inspiration from Super Mario World and rubber hose-style platformer Cuphead, conceiving an animated visual of a forlorn, nameless bird-like character navigating an island. The album’s artwork, meanwhile, incorporates imagery of one of Rodin’s Thinker statues, vandalised and stolen from the Singer Laren museum in 2007. Stark imagery of its damaged head, following attempts by thieves to reduce it to scrap, left a lasting impression on Zawada and the idea of using it as a key visual was mooted early on.

“Over the course of such a long project, having something like the cover settled throughout was quite a good anchoring. We didn’t do that consciously, but in retrospect, it was really useful to have had something to sort of tether ourselves to every now and again.”

The humble album cover remains an important touchstone for Zawada. Today, his involvement with music projects often extends beyond the creation of a mere sleeve and while its relevance today has been somewhat renewed by the ongoing vinyl revival, Zawada is rueful of the way in which its significance was previously reduced to little more than a square digital image.

“It’s a much more challenging, interesting thing to think of a still image that can summarise 70 minutes of music than videos and all the rest of it,” he muses. “The few times we talked about it reducing down, you always end up in that silly discussion of, ‘Well, it’s this big and you can’t really see anything’. We had a lot of discussions about that: a version of it which works better digitally, but looks nowhere near as good as a physical thing. We made the conscious decision that prioritising the vinyl was probably the best thing for us to do, just out of selfish reasons.”

As for the role of the artist within music today, Zawada is mindful of wanting to stay true to his creative integrity and intention. To him, Tall Tales is a reaction, of sorts, to the way that some artists and directors historically co-opted music videos as a backdoor to commercial work.

“I feel like the commercial art production process has infiltrated the way we think about everything. There’s artists that have employed that really well in a critical way that I respect from the 90s, but I think it’s become more pervasive than that. I think we assume that every music video, which is really just some artists making some artwork, should be treated as if it was a TV commercial and produced in the same way.

“I think that’s what my little protest in this whole project is against: the idea that we should be treating music videos as if they’re a test run for when you get a perfume commercial…. They’re an artform. It’s an artwork in itself. And if I was making this as an art piece for myself, this is how I’d want to make it.”