The Monthly Interview: Jessica Hische

In our latest monthly interview we speak to designer and illustrator Jessica Hische, who has built a hugely successful career spanning commercial work, books and even retail. Here, she reflects on her life and work and how the industry has changed during her career

It’s Jessica Hische’s 40th birthday on the day we meet. She is spending this ‘big’ birthday in Barcelona with her family, because she is headlining the main stage at Offf Festival in the evening, where she will share advice and experiences from her career to date, framed within the different decades of her life.

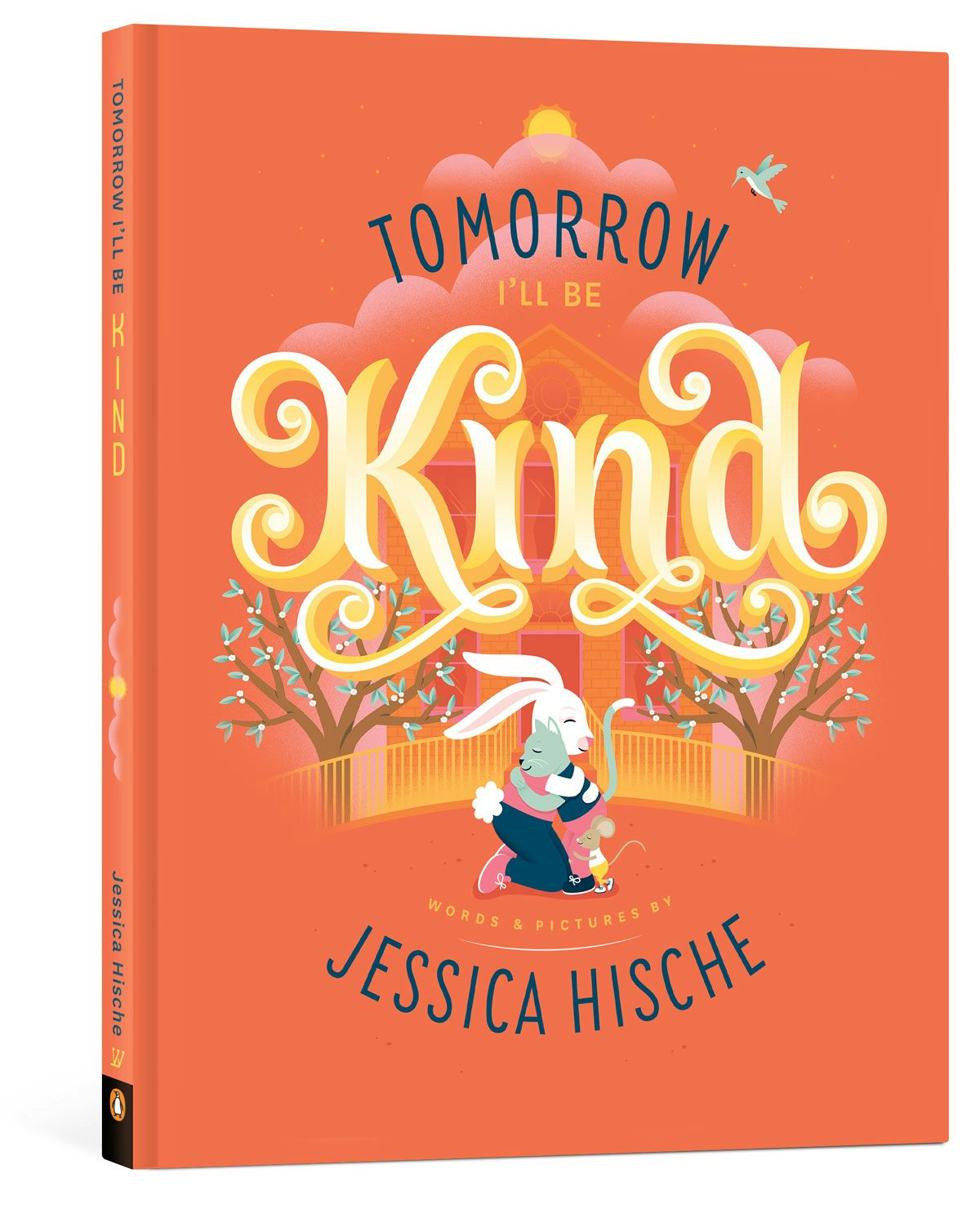

This blurring of life, work and family feels apt for Hische, who is open about how much these different elements are intertwined in her practice, which is vast and eclectic. She is perhaps most renowned for her lettering, type design and illustration, but she has also published kids’ books, and runs two bricks-and-mortar stores near her home in Oakland, California. In addition, she teaches, speaks at conferences, and has a 200,000+ following on Instagram.

When describing her work, she still returns to her design roots, however. “It’s still lettering; commercial lettering, logo work, advertisements, things like that. Because most of the other things that I do are … more self-authored. I don’t want people to come to me to create a brick-and-mortar store for them. Those are things that I just do for myself as part of my business, but in terms of interfacing with clients it’s the same old story and the majority of my work is commercial lettering work.”

Hische’s character shines through in the work that she does. She describes herself as an “oversharer” but is great company, warm and open, though with a clear sense of high standards and a desire to steer her own ship. As her website puts it: “I strive to create beautiful and legible work with just enough personality and a high level of technical precision.”

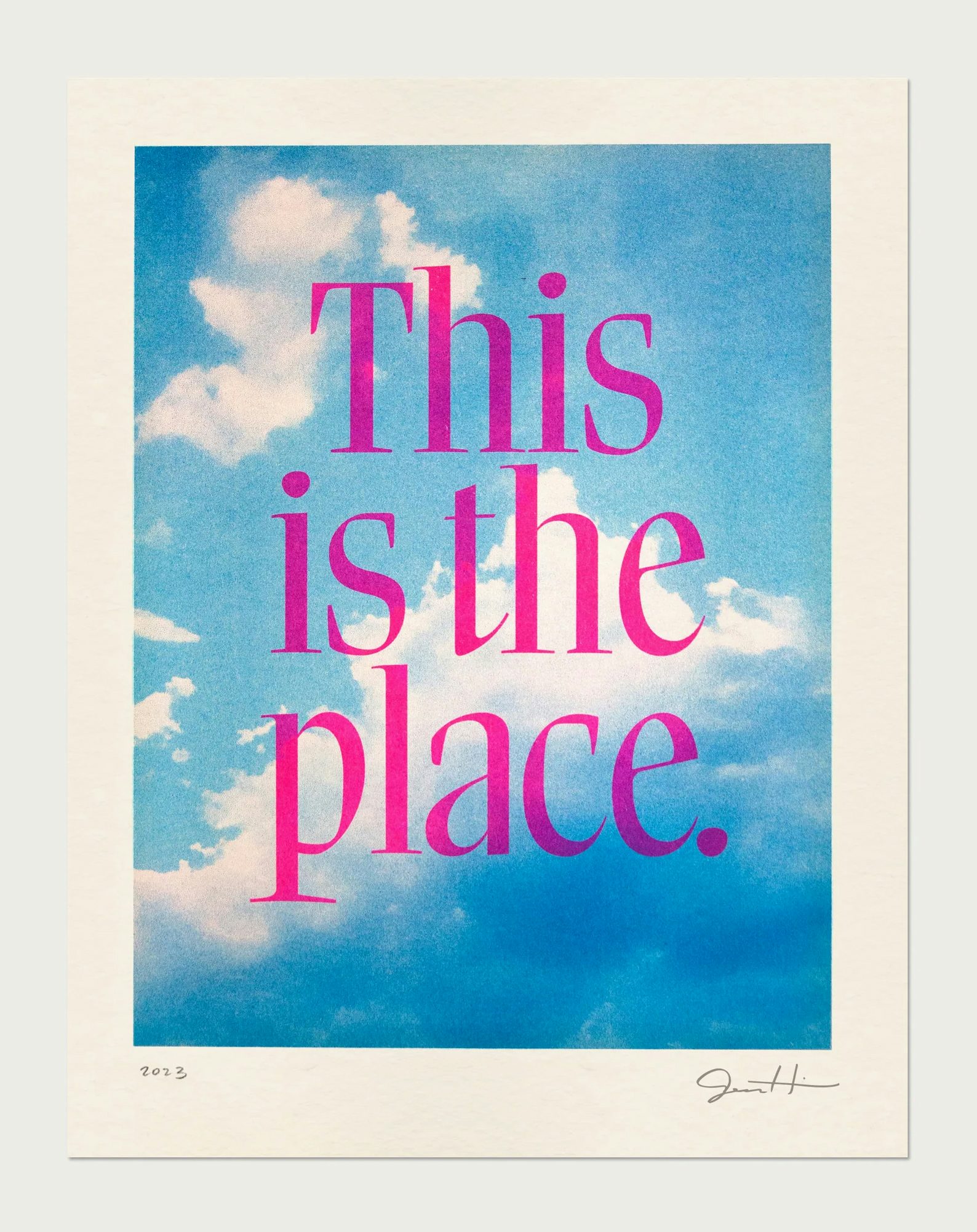

This has led to work with huge corporate names from Apple to Neiman Marcus, Mailchimp to Nike, as well as picking up dream creative commissions such as creating the titles for Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, or more recently the poster for Lionsgate’s Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret. Her commitment to quality extends to her side projects too, with Fast Company describing her first shop as a “dreamy retail destination for designers”.

With an output this prolific, it is surprising to find that – in design terms – Hische still operates as a broadly solo designer. “I have my own studio, but technically my only employees are myself and my mum,” she says, adding, “if you receive a package from my shop, you receive it from my mum.”

There are other collaborators of course, but working this way on her designs is deliberate in order to stay close to the creative work. “I’ve kept it just me because I don’t want to turn into just a manager,” she explains. “I want to still be creating the art. And I just realised that I need it, for my mental health. If I start hiring designers to work for me, I’m putting myself purely in a management position and doing very little of the actual physical making.

“For some people, that’s what they want. They get bored of the physical making, or they want to, you know, have AI help them with it. For me, it’s just like, ‘Nope, I want to do this as slowly as possible. I want to use my physical hands.’ I really need it. And I didn’t really realise how much I needed it until I found myself taken out of the process a little bit. Any time that happens, it just means I have to pay for more therapy. So it’s very cost-effective as a result. If I can get paid to do my therapy, it’s much better than having to pay someone else to do my therapy!”

Hische is quick to acknowledge that there is a need for balance, however, both in terms of taking on help when it’s required and also maintaining variety in her output. “I can’t do everything. Like if I’m working on a kids’ book, that is very labour intensive. But then all the lettering work that comes in or commercial illustration work, I end up doing sketches for it but then having someone else help execute the other part. And to me that’s not ideal because the ideation and the sketch part, while fun, is much more stressful because you have to be really present. Trying to convey the idea is very thought-based and I love to do that. But if I did it all the time, I would burn out.

“The counter to that is the time I spend in just pure production that’s like mindless vectorising, which I really love to do. It balances out that more cerebral time for me. A lot of designers get bored with the production and feel like it’s not worth their time. But for me, if I don’t have that, then I eventually just get so burnt out on the ideation and sketching and creative directing that I need longer pauses where I’m not creating anything. Where if I mix production into it, I feel like I can just keep at a nice steady pace and never really feel burnt out.”

Hische is also open about her family life. Her kids, aged eight, six and four, are in Barcelona with her and she addresses them during her talk. There is a confidence in her ability to mix work and motherhood, and be candid about this, that is inspiring, so it comes as a surprise to discover that she still feels that family life has impacted her design opportunities in some ways.

A lot of designers get bored with the production and feel like it’s not worth their time. But for me, if I don’t have that, then I eventually just get burnt out

“I draw a harder line on my schedule because I want to spend time with my family. It cuts me off from certain kinds of opportunities and work, you know. There are things that people don’t come to me for because I’m visibly a parent – things that involve travel for work, for instance. It’s an instinct, but the instinct was validated when I had my daughter and I was posting about her on Instagram, and my work dried up for six to eight months. I mean, I went back to work at four or five months because I was like ‘time to work again!’. You know?

“And it was like 11 months later, and I got an email from an art director that was like, ‘Hey Jess, not sure if you’re back at work yet?’ And I got a lot of other emails being like, ‘So you work from home now, right? With the kids?’ And I’m just like, ‘No!’ People make assumptions, if you will. And what I realised is that I have to really control the signal that I put out, to assure people that I am working and that I am working full-time.”

We are currently experiencing a boom in type design, with technology allowing designers to be far more playful with type than was once possible. Hische’s career has developed alongside these changes. “When I was starting out a lot of that didn’t exist. I started in lettering, because I would find a font but it would be 70% of the way I wanted it to be. So I was like, ‘I’m just going to draw this and it’ll be better.’”

Hische has watched the industry around type design explode, in a way that has diminished some of the need for hand-drawn lettering. “Type design as a field has really grown. It’s become really very exciting, and in wonderful ways because I do feel like there needed to be more graphic designers creating typefaces. They have their finger on the pulse of what people want in design, versus type designers making designs for type designers.

“You know, I’m still happy that that exists because they make beautiful work and they’re also in this wonderful silo of not necessarily paying attention to trends and just making things that they believe should exist based on their own personal tastes. It’s nice that there’s the two worlds.

“But because there are so many graphic designers playing with type design and then taking it very seriously and becoming type designers, the world of display type has completely exploded, in really great ways. Before, all of the good fonts were workhorse body fonts, and the display fonts were very hit or miss about the level of quality. But now there’s tons of really high-quality display fonts, which definitely can take the place of lettering a lot. It’s one of the reasons why I’ve really moved my practice towards doing logotypes.”

Another industry change that she’s observed in recent years is the merging of designers and influencers, with clients hiring a specific designer in part due the personal attention they can bring to a project.

“I think that a lot of times clients try to accomplish whatever they can in-house just because it’s more economical. There used to just be a ton of nameless, faceless commercial work going around where I’d get hired to draw letters for a Colgate ad and in no way was there any requirement or pressure to post that on the internet, or have my name associated with it or anything. And I think that because of the explosion of social media and advertising, and the turning towards influencers a lot more, it means that a lot of that kind of commercial work is not only creating the work but also commodifying part of the artist.”

It’s clear that Hische has mixed feeling about this process. “I really don’t do a lot of influencer work at all. If you ever see anything that says ‘paid promotion’ on my Instagram, it’s very, very rare. And I only say yes when it’s something that I already personally endorse and love. There’s a genuine thing. But I think I’m a rare instance of that. I think most people don’t care.

“I have these really specific feelings about it, because I rose up in the design world sharing all of myself. People follow me because they follow me. It’s not just about the work, and so, to me, it just doesn’t feel right to give away parts of me to companies. And also, I’m very focused on legacy, and not just because I want to be famous or whatever.

I really don’t do a lot of influencer work at all. If you ever see anything that says ‘paid promotion’ on my Instagram, it’s very, very rare

“I have three kids, I think about them in their 20s and 30s looking me up, like, ‘what was Mum into when she was our age?’ And I don’t want it to be a false interpretation of me. I really care about that. And so I’m very careful of it. Because my biggest goal ever is for when people meet me, that they feel like it’s the same person that they’ve known for years online. I want to be that person. It’s satisfying.”

Age is something that is not talked about a huge amount in the creative industries, perhaps in part because it can be an ageist world, so people want to underplay the age they’re at, and maybe because design is so often viewed as being somehow separate from the person who made it. It is therefore refreshing to hear Hische talk specifically about aging at Offf, and about how her work and ideals have changed over time.

Many of these learnings come out in the advice she imparts to those entering the industry, which centres on embracing “the stage that they’re at”. “Understand that naïvety is actually a superpower – because you’re going to make so many weird mistakes,” she says. “Just really be curious and push yourself to try new things.”

Hische also advises against solely chasing money. “If you want to create the life that you want to live and you want to work to live, not live to work, just having that in the back of your mind is really important. When you’re 20 and starting out, you want to live to work because the work is just so exciting. And you feel so alive by it. I still love the work. But if you’re like, ‘hey, here’s five days to do whatever you want’, I’m going on vacation! I’m going to go lie on a beach! I’m not going to spend five days making posters. And I might have done that when I was 24 because I would feel like, ‘finally I can do those creative things I never had space for’.

“Now, I know that there’s space in my life for things that are not just creating work. And that I have hobbies and interests and want to travel the world and spend time with my family and things. But that shifts. When you’re starting out, embrace the fact that all you want to do is work. It’s exciting. That goes away eventually. And you’ll have a big existential crisis and then you’ll come out the other side and feel fine.”