Glenn Kitson arrives clutching a coffee, something he’s recently “relapsed” into because of all the travel he is doing as his directing career builds faster than his Instagram following. “You just can’t not have coffee with jetlag,” he says. “It’s a slippery slope though!” This self-deprecating wit has added impact, as he’s been refreshingly open – in an industry habitually guarded regarding personal struggles – about being in recovery for years now.

Represented by mega-production company Iconoclast, he’s recently made spots for Nike, Berghaus, Clarks and the World Cup on ITV. Today’s coffee is because he’s been up half the night, working on pitches for two jobs. He likes to work late, and to have a few things on the go, and last night, inspiration hit. “I was in bed and had to get up and email myself in the middle of the night because I was inspired by a particular shot in a film that I wanted to use.”

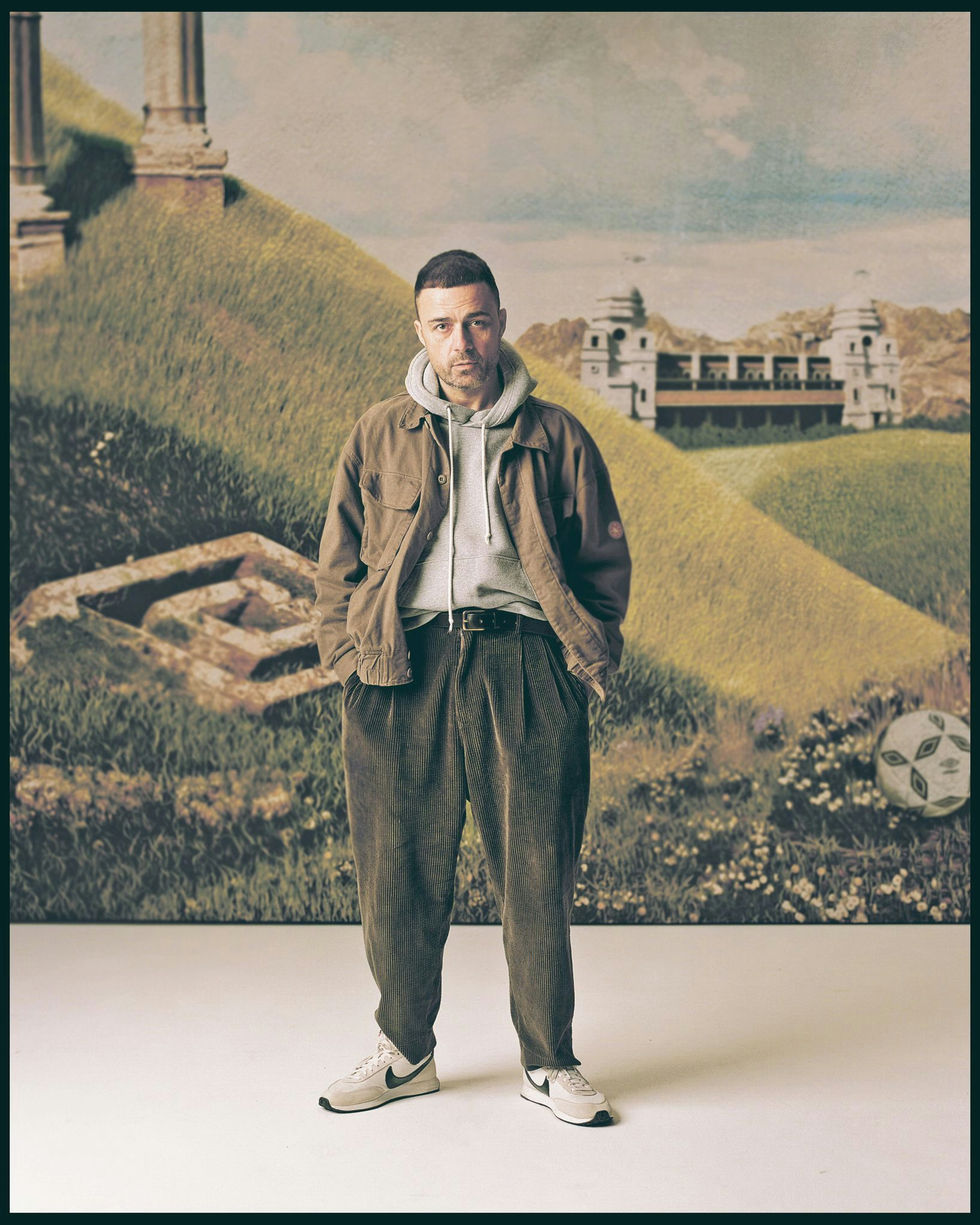

To the casual observer Kitson looks like guys I went to school with: outdoorsy streetwear. But if you look closely, you’ll see the trousers, knitwear and big jacket are impeccably put together. It’s the ‘quiet luxury’ of Succession, by way of Bolton.

Nights, he says, are good for writing, as his partner and two kids, and their “nuts” sausage dog are in bed. “I’ve always felt more lucid and I get into a space where I can write.”

And writing is important as he starts each day with his “pages”. Kitson worries he sounds too new-agey, but for him, “it’s about getting present. At the end, I write intentions. And part of that is to remain open-minded, to remain teachable. I should be doing three pieces of A4, but that means I’m there for an hour and I need to get out of the house! But I have to do it, so I get up early and do my morning pages, or in my case, morning page.” Following the model from Julia Cameron’s The Artists’ Way isn’t groundbreaking, but his use of it plays an interesting part in how he manages to stay engaged in a rapidly changing culture.

“I’ve noticed, a lot of men in particular, the older they get, the more close-minded they become. Like, ‘everything’s shit. It’s not as good as it used to be.’ All that kind of stuff. And I find that really dangerous and really negative. And I don’t want to be one of them. Don’t get me wrong, I can be as cynical as anybody, but I’ve been doing this for seven years now and it’s definitely changed my outlook on life positively.”

Those intentions are really important for someone who has come as far as Kitson, 47, has. He left school in Bolton early and got “swept up” in the rave scene which eventually led to him living on the streets from his late teens to mid-20s.

Several spells in rehab during the early 2000s battling addiction finally saw him sorting himself out via a more rewarding habit – trading vintage sportswear. Then he traded himself up through the ranks of styling, brand consultancy, and founding his own men’s magazine. A northern lad’s answer to The Face, he still runs The Rig Out as a photography and strategy studio today. In pages and in recovery, Kitson says, “it’s all about getting honest and in the moment.”

View this post on Instagram

In some corners, Kitson is now more famous as a ‘meme lord’ on social media than as an ad director. Thanks to his pop culture lookalike posts, Kitson has cultivated influencer-level followers on Instagram. His account, he says, really took off in lockdown because he was “bored and doing a lot of little tiny projects just to keep my head going”. He migrated to Instagram from X after he was banned a couple of years ago for “bullying the EDL”.

“I’ve always had a few followers because of the styling I did before I was directing. I’d always put a few memes in there too because it’s funny to take the piss out of yourself and take the piss out of the things that you’re into.”

Trying to get something made these days is difficult without a committee trying to smooth all the rough edges off. And those are the thing that’s going to make the thing great

Kitson says a few friends have fallen out with him as they feel protective of some of the people he features, “like New Order. But I’ll do New Order because I love them. I love Roy and Haley from Coronation Street. For me it’s being part of the culture.”

And that work connects him in a way that being a jobbing director doesn’t. “This is the weird thing… You kind of learn in silo from other directors. It’s not like certain careers where you are mentored or an apprentice. I observed people that I worked with before I was directing, but when you’re on the job, a lot of it comes down to learning by doing. I have got friends that I can ring up now, but it took a while to get that sort of access to a resource like that.”

So he reviews his work, unpicks his decision making, works out how to evolve in a world that often just wants successful directors to rinse and repeat. His recent spot for Berghaus – an acid-trip mind-melt of a film – is a good example of this. “[They] came to me because I did a small job for Nike three years back where I just went up to Liverpool, shot it myself and I changed the process.”

The budget was tiny but that meant he could experiment more for a big brand. “I interviewed a lot of people, shot loads, had a lot of crazy ideas, all sorts of animation, analogue stuff. But first I took all the interviews and made a track, with composers I work with a lot. So the audio came first and then we edited the footage to that.”

And so the new client asked “could you do something like that?”. Kitson says he’s been there before, making the same job for the money, but quickly found he was unhappy and unsatisfied, and the work showed the law of diminishing returns.

“That thing that everyone liked, I didn’t hit that again, you know? So I said, I can do the same process but I don’t want to do the same work. I want to approach it differently visually. So with Berghaus, rather than analogue animation, I used AI instead. I wanted to use it, because it’s a new method of working.”

He is at pains to say this experimentation didn’t play to alarmists who think AI will put all of us out of a job. “We still shot everything, still had the same crew, there was nothing generated that hadn’t already been filmed. And if there was, we created it with VFX, so there was still that whole team. It was exactly the same process I would use for anything, but we had this other layer, on top, of artificial intelligence.”

The film was a sensation, so pushing the boundaries worked. “I’m not an expert. On the next job I might completely fuck it up. But I try not to be patronising, or condescending. Some of the great adverts, especially in the 90s, you’re kind of not allowed to do anymore. But that’s how they connected, because they had wit and a sense of humour and energy.

“Trying to get something made these days, whether it’s commercial or non-commercial, is difficult without a committee trying to smooth all the rough edges off. And those rough edges are the thing that’s going to make the thing great.” That’s where Kitson sees his, and fellow creatives’ role, to “push back and fight for those rough edges”. He’s hopeful for the future though, despite attention spans shifting amidst a sense of over-saturation, and being asked to deliver nostalgia, not the now.

“You’ve got to do unexpected stuff to connect with people and draw them in and keep and hold them. Every brief I get is ‘can you make a film about the 90s and raving in Manchester?’ My answer to that is I can, but I want to also set it in the present and somehow draw on the dots between the past because the more you talk about the past, the less you’re saying to this generation. You’re telling them the good times are over, there’s no hope for the future.”

And there are a lot of emerging talents inspiring him. “Great work will always come through. Love Song – Daniel Wolfe’s production company – are amazing. There’s a pool of directors that he works with – Eliot Power, Verity Lane, Bafic – I look at their work and just think ‘yeah that’s great, I want to be as good as that or better one day’.”

View this post on Instagram

And to do that, Kitson says, he’s going to stay open, and keep pushing himself. Self-initiation is what ultimately got him where he is and keeps him going. That’s his central advice for new talent too.

“When I started the magazine, I didn’t have a proper job. I was doing three or four different things to earn money. But I spent whatever I had on putting the magazine together, until that got seen and noticed,” and that, says Kitson, is when brands began to pay him for his time and work.

That doesn’t mean the lad from Bolton feels this is ever easy. “Every door I’ve knocked on and every call I’ve made I’ve had a fear of ‘I shouldn’t be here, I shouldn’t be doing this, I shouldn’t be doing that’ but it’s just telling it to shut the fuck up and do it anyway. I’m what they call a mitherer back home. I’ll mither. I badger people. It either puts them off me – or I get what I want.”