The art of writing a brief

We look into why briefs are so imperative to get right, the difference between advertising and design briefs, and whether visuals have any place in them

The always-on communication between agencies and their clients would suggest that briefs have a less important role than they once did, because who needs a few paragraphs buried in a word document when you have WhatsApp? Yet Laurent Simon, chief creative officer at marketing agency VMLY&R, believes they’re more essential than ever.

“Everything is faster. We’re poorer in time, poorer in terms of budgets, there’s more channels you can use to connect with people. It’s not just a radio ad or a TV ad or whatever,” he says. “So the more clarity and the more consistency you can have, the better, because whilst the creative process is not an exact science, there are things that you just can’t do without. You need to know where you’re starting from and where you’re going.”

The brief doesn’t just provide a “north star” for creatives, Simon explains. “I’d say it’s probably one of the most important documents you can find at an agency. The reason being, a brief is, I guess, one of the closest manifestations of a contract between agencies and clients.” Without the luxury of time, budgets, and a consolidated audience that he experienced when he first started out, he finds that “you do need that cornerstone in black and white telling you precisely what the ask is and what the objective is and what you’re trying to achieve”. Even in his time as ECD at BBC Creative, where he was theoretically much closer to the ‘client’, the brief was essential for keeping everyone on track.

Design strategist Silas Amos echoes that a brief should clearly indicate client expectations and, ideally, a concrete outline of what to measure them against. “Oftentimes briefs lack judgement criteria. There’s an assumption that the agency and the client are all on the same page, that they all understand the same thing.” Fleshing out judgement criteria is helpful when it comes to reviewing the work with the client and turning subjective responses into objective evaluations. “If the client says, ‘I don’t really like blue, I’ve never been a fan of blue’, that’s obviously subjective and nothing to do with anything.”

Asking how long a brief should be is like asking how long a piece of string is. The answer will vary depending on the case, but to Simon, you should be able to condense it down if necessary. “Very simply a good brief is just that. It’s good and brief!” he says. To him, it’s fine to come up with 30 slides packed with detail and references or “a piece of paper that’s got five words on it”, but “you do need the one pager”, he says. This is partly so everybody is accountable, but also because a short, straightforward description is more accessible for people in the team with a shorter attention span. “You know that if you brief them with a deck that is 60 slides long, you’ve lost them after three slides.”

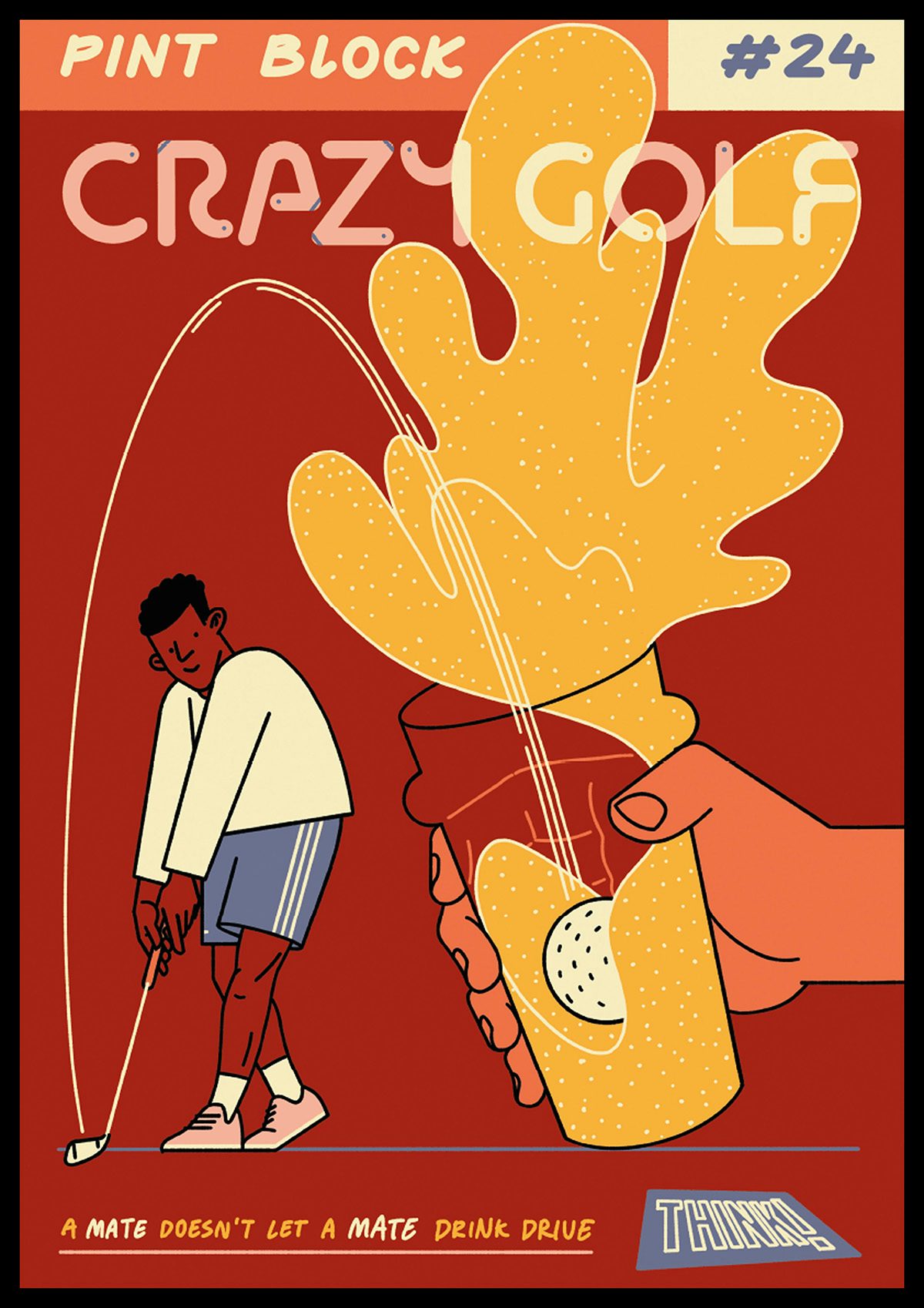

While Simon believes you still need “that sentence, that phrase, that proposition” that clearly defines the ask, he explains that some creatives are more comfortable with words and others respond better to visuals, which perhaps explains why he’s seeing more briefs with visual references these days.

Even if pictures don’t appear anywhere in the brief, Amos says designers respond well to a written brief that gives them something to visualise in their mind. “I think marketeers, typically, are pretty comfortable with words and aren’t necessarily people who think in pictures, but designers are people who think in pictures. So it helps if you’re given a brief which comes from a think-in-pictures mindset, rather than, ‘here’s 500 words, do a label for that’.”

He says that the problem with a lot of design briefs boils down to where they’ve come from. “In the typical old pecking order of life, the comms agency was in first. There’s 500 of them, they’re big money, they’ve done some heavy lifting on the strategy, and they’re doing it all of course with an aim to broadly making a TV ad.”

Some briefs are still too company-centric, as opposed to being audience-centric. Just because it’s interesting to the client, it doesn’t mean it’s going to be interesting to the public

Amos thinks that’s starting to change as design and branding are increasingly getting a seat at the table from the beginning, but “it’s not gone away yet, that idea of creating a story and such like. So [the brief] tends to have a slightly narrative-based genesis. And sometimes, the things that have been agreed within the comms brief almost get handed on, unfiltered,” he says. “It’s like, ‘OK, we’re doing this story about bringing people together at mealtimes’, let’s say. I can totally see how that comes together as a TV ad. How do you draw a label that does that?”

He also points out that an advertising campaign and a rebrand, for instance, are going to have a totally different shelf life to one another. “I suppose the other thing, to just be slightly cynical, is that the narratives and big ideas and words from an ad agency change every spring. It’s in their interests to keep telling different stories,” he says. “Whereas applied design, when you put it into packaging, it’s much less agile, and much less something that’s easy to keep changing because you just shoot another campaign, if you see what I mean. It’s stuck with it. So [a typical design brief] has to go to some slightly more bedrock-y place.”

To Simon, the brief needs a skeleton that answers who, what, where, when, and why. This last point is one that can be easily overlooked. He says that the brief should get across “why I should care”, because if the creatives don’t care, then the audiences aren’t likely to either. “The part of the brief that I pay a lot of attention to is the proposition, that word that you see in bold on that document, and almost regardless of everything, that line should convince you. That line should convince you because it’s putting forward what the team thinks is the best argument or the most compelling argument. So if that’s not the case, then you know that this already is a challenge. You need to go back in for further discussion.”

He describes strategy as “frontline creativity” that gives creatives the building blocks of a direction. As such, any insights shared at the brief stage can be golden. He believes that more strategists or planners should be aware that “broad doesn’t necessarily mean big” in terms of scale. “If you’ve got broad thinking, what you’re going to end up with is just broad creative. Broad doesn’t equate to big. And equally, niche doesn’t mean small. Niche can actually be the springboard to something that’s going to be far bigger and greater than you ever thought in the first place.

You need clarity, direction, a degree of precision, but you also need an openendedness to allow the creativity to interpret what you’re saying, rather than it being specific and literal

“It’s really useful to have those nuggets of niche data in the brief, because quite often they’re less familiar than the other insights or data that you could have seen. If the input is more interesting, the output will be more interesting.” This brings Simon onto another crucial point – that “what you put in a brief can be factually correct, but that doesn’t make it interesting or relevant”. Though he sees this less and less, some briefs can still be “too company-centric, as opposed to being audience-centric. Just because it’s interesting to the client, it doesn’t mean it’s going to be interesting to the public.”

Detail and insights are useful, but it’s important that briefs don’t encroach on the creative response by being prescriptive. “You need clarity, direction, a degree of precision, but you also need an openendedness to allow the creativity to interpret what you’re saying, rather than it being so specific and literal that all you’re really doing is colouring in,” Amos says. “So there is always a balance of not being so clear that there’s no room left to do anything and add anything, and yet on the other end, if you’re not clear enough and you’re leaving things too open-ended, you don’t have the classic phrase ‘freedom of a tight brief’. Tightness, and using that as a springboard, I guess, is the happy medium.”

For Amos, an inspiring brief has space for contrasting directions, which allow creatives to search for a unique sweet spot in the middle. “You’re almost trying to find two turns of phrase that you can picture which are pulling in two directions, and where you can resolve that tension, you can get to something that’s a little bit different.”

The best design briefs, in his view, simply get to the crux of a brand or a product or a service and why it exists in the first place. “I think design is such a blunt instrument, you have to go for the jugular a bit with it and then boil it down. Advertising to me is like a play or a story or a novel, and design by its nature is this thing that just sits there passively, oftentimes – it’s a haiku. So you just have to be quite reductive to get it down to an essence, because you’re not going to be given the luxury of this outer storytelling world,” he explains.

“Though that’s blending now because we’re in our digital mutatable world. There’s an opportunity to tell richer stories and do richer things through the medium of branding and design. But really, that opportunity is best realised when you’ve still got something pretty granular at the heart of it. It’s getting a lot from a little.”