Exposure: Adali Schell

At only 23, the LA-based photographer has already been producing imagery for half his life, using photos to document and digest his surroundings

It can be difficult, and often premature, to try and distil the impetus of a young photographer’s practice into words. They need time to experiment, try and fail, push the boundaries of their perceived limitations and grapple with the complexity of being a photographer.

And yet, unlike previous generations, many new graduates enter the industry with a clear point of view — a desire to ask questions about specific themes or aspects of contemporary life — that transcends ambition or survival. This early cohesion is born from the fact that their lives have already been entangled with a camera for over a decade, living a life through a lens for over half their lives.

“I don’t know where I’d be without the camera,” Adali Schell tells me from his apartment in Miracle Mile, Los Angeles. “From my parent’s divorce and losing family members to heartbreak and isolation, the camera has been really the only thing I could count on.”

Schell’s first camera was a fourth generation iPod Touch, and the process was instinctual: “I was a nervous, awkward kid who didn’t have many friends. Taking pictures was a coping mechanism and, for some reason, just made me feel better. I would wake up with this quench to be in the world with my camera, and anything that got in the way of that, like school or dating, turned out to be a problem.”

Schell, who is 23, spent the first 14 years of his life in Los Angeles before his life was interrupted when his family relocated 100 miles away to a small town called Murrieta, part of Riverside County in the Inland Empire. The move was devastating for Schell, who had been taking pictures for three years and was starting to find a sense of self through photography.

He spent the next four years on pause, numbing himself with Call of Duty and spending almost all his time inside and alone. When his parents divorced, he was able to return to LA and wasted no time enrolling in an arts high school. He started building a creative community and, after a long break, finally picked up a camera again.

Inspired by the work of Vivian Maier and Helen Levitt and armed with expired film he bought on eBay, he began to work on the LA public transit system during his morning commute. “I had been so removed from the city that just to be in a public space with all these people, sitting close to strangers, made me feel part of something again.”

Just as Schell began to settle, the pandemic began one semester into his senior year. Classes stopped, and graduation was cancelled. Being unable to make work outside meant turning the camera on himself and obsessively photographing every detail of life during quarantine. As lockdown lifted, Schell began taking long bike rides with his camera, capturing the city from a new vantage point.

“It was a rewarding and responsive way of working,” he tells me about that strange time. “If I saw something, I could throw the bike on the ground and just start shooting. Ironically, the only reason I stopped making work this way and got my driving licence is because my bike got stolen.”

Vehicles have always been a sacred place for Schell. “Growing up in Los Angeles, the car was my respite,” he tells me. “Specifically, my dad’s vintage 1980s Mercedes, which he converted to run on vegetable oil. The engine’s hum, the tears in the leather interior and the sound of his burned CDs accompanied my earliest understanding of the city.”

This affection manifested into his first significant body of work, Car Pictures – which coincidentally became the first of many assignments for the New York Times — where he documented first cars as a poignant space of connection and exploration for his peers.

“Having spent my final teenage years in isolation due to the pandemic,” Schell explains, “the car provided me with a space to come back into touch with my community.” Through his dad’s old Mercedes, a beat-up Volvo, a ‘mom’ car and a former taxi cab, we are privy to the newfound freedom of a generation coming of age both in a pandemic and a highway bound city.

Car Pictures is currently being made into a photobook and will be exhibited at the Leica Gallery in Beverly Hills next year. It is a visceral embodiment of young adulthood, and yet it runs much deeper for Schell than a study of youth culture. “While this project concentrates on the car as a nostalgic and connective force, born from my longing for the youth I never had in LA, the car is also a nuisance,” he tells me.

“It interferes with your existence here when it comes to meeting people and living your life. There are so many implications of the car industry, from climate change to the city’s history of exclusion through city planning that marginalised the lives of Black and brown communities. The car is a way to unravel many complex issues.”

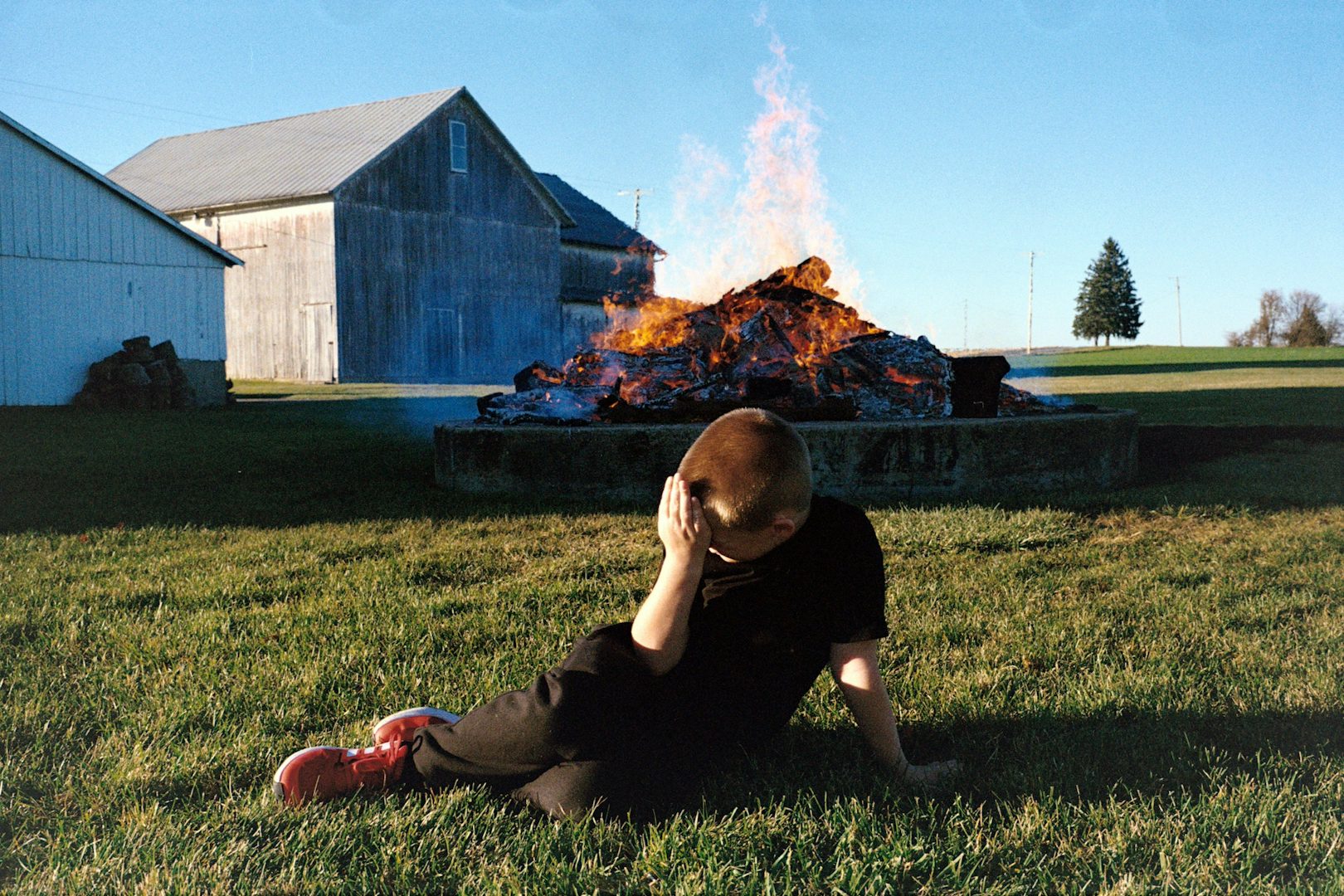

To date, Schell’s practice exists at the intersection of transportation and isolation, unravelling how being together in these transient spaces can be a salve for the loneliness of modern life. And yet, in direct contrast, his series New Paris is an intimate exploration of family dynamics, exploring his Mother’s Irish Catholic family who live in a small town on the Ohio-Indiana state border.

Rooted entirely in the domestic, Schell grapples with the political, social and familial in a body of work that feels like it pays homage to work like Richard Billingham’s Ray’s a Laugh. Through these candid and irreverent images, we get a preview that Schell has much more to say with his camera.

“My obsession with taking pictures was one of my first realisations about myself,” Schell tells me as we end our conversation. “I would go as far as to say it’s the only thing I know about myself. It’s the only thing that lasted with me unconditionally for the last decade. I just turned 23 a few days ago. And I realised I’ve been doing this for over half my life.

“I think many photographers pride themselves on these big decrees of ‘this is how I see the world’ or they are on a ‘search for truth’, which I really reject. For me, the camera feels like someone holding my hand when I don’t know where to put myself. It somehow makes the world a little more digestible.”