Exposure: Ashley Markle

Gem Fletcher talks to the photographer about her process, in which she works with family members to examine their complex relationships, challenging all participants to face up to uncomfortable truths

On a sunny day in September, photographer Ashley Markle met up with her father, Bob, whom she had recently reconnected with after a decade of not speaking. As they walked around Mosquito Lake in Bob’s native Ohio, they paused by the sandy shore, and Markle laid her camera down on a rock.

Standing a few feet away, Bob was caught off guard when Markle ran and jumped at him, snapping a frame as she collided with his body. The image is a sucker punch to the gut, laying bare Markle’s trauma of abandonment while Bob braces for impact, unsure whether to hold her or push her away. “That image felt so powerful when I first saw it because it felt like I was taking a leap of faith,” the New York-based artist recalls. “I was opening my soul to him for the first time.”

For anyone with complex relationships with their father, Leap is one of those images which makes you feel seen while simultaneously poking at an open wound. It is a chaotic tour de force made more potent by Markle’s audacious faith that despite being estranged for over a decade, her father would be there for her – that he would catch her.

Like many men, Bob was raised on a breed of masculinity where vulnerability and emotional availability were not just a foreign concept but the antithesis of the societal expectations of manhood. The question Leap asks is not whether or not Bob will catch his daughter but whether he even knows how.

The photograph from the series Do You Know How Beautiful You Are is emblematic of Markle’s approach to image-making: absurd, playful, provocative and emotionally complex. Photography, for her, is a wayfinding device. A methodology to grapple with the personal and sociological that centres the body as a conduit of the ineffable. Her images don’t tell you what to think – “I’m just never concerned with what other people think about my images, to be honest,” she says – but rather, her practice is simply a portal into her journey.

“Throughout my adult life, the vision I had of my father was formed through hazy childhood memories and understandably biased stories from my mother,” explains Markle, who has been working on the project for five years. “I thought of him as lazy, party-obsessed, unintelligent, and selfish. So, when I began photographing with him, I recreated childhood moments I missed out on, visually screaming at him for missing such a big portion of my life.”

As their relationship deepened, the project’s tone shifted as Markle gained context into her father’s past. “His perceived laziness became a desire to wind down from a lifetime of working gruelling manual labour jobs,” she says. “His inability to control his temper and abide by authority figures existed because of uncontrolled mental health issues which ran rampant in the Markle family. Having experienced countless hardships and tragedies, [it turns out] the Markle family is resilient and holds onto the love they have for each other to survive.”

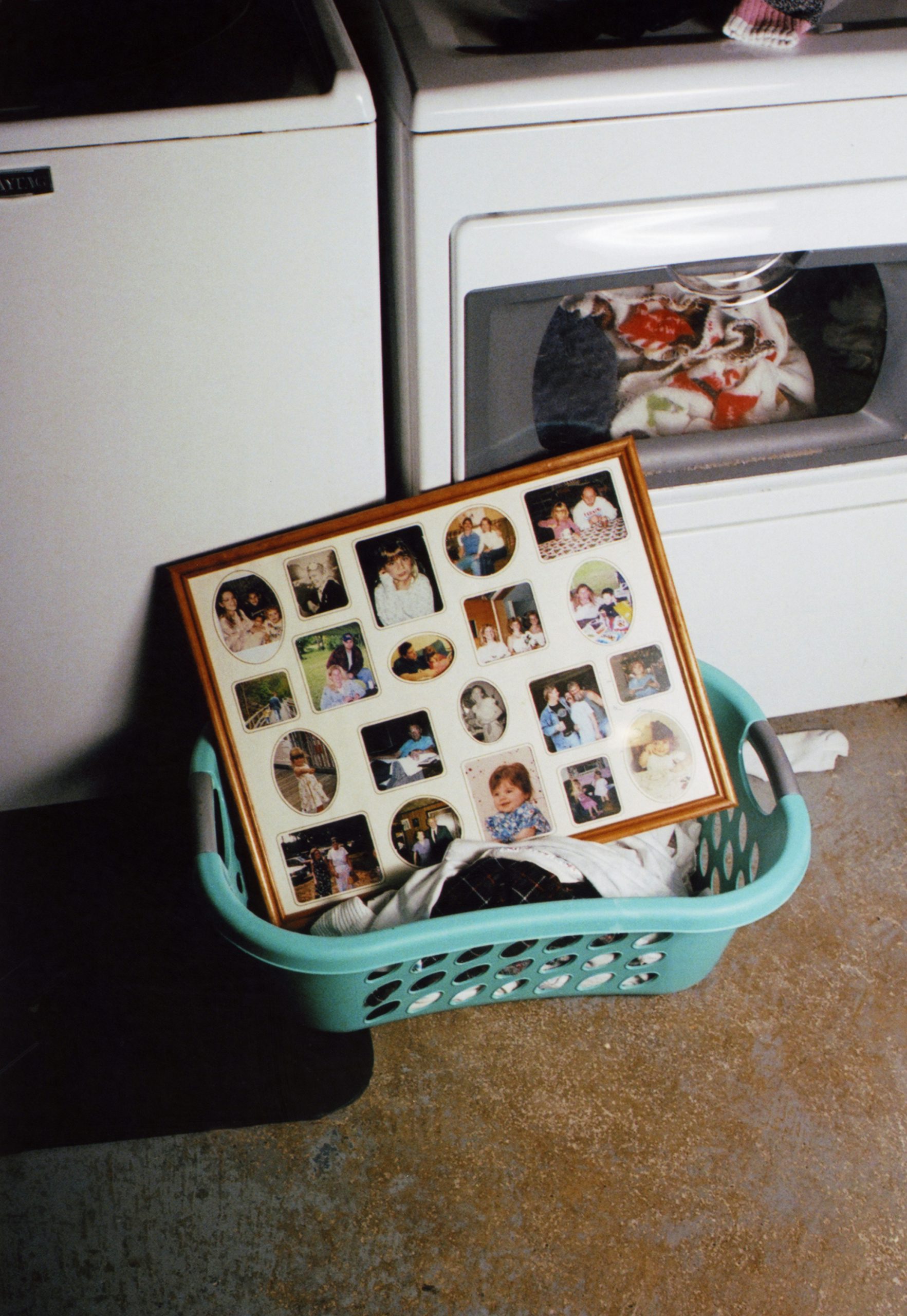

As the project changes course, the initial tension and discomfort are replaced with a portrait of appreciation as Markle documents Bob’s life, putting him on a pedestal as they reconstruct their relationship. “I just always felt like an alien growing up, never understanding where some of my anger and distrust came from,” Markle shares. “Spending time with my dad made me realise I’m a carbon copy of him, and the work became a love letter to him and myself – finally accepting myself for the first time in my life.” The ongoing project is in dialogue with Charlie Engman’s genre-defying work, Mom. Two bodies of work that unravel the conventions of intimate relationships and what it means to look and be seen.

Destabilising familiarity is the throughline of Markle’s practice. As she began collaborating with her father, she simultaneously worked on Weekends with My Mother and Her Lover, a potent body of work examining the sexual politics in familial relationships. “It has always been interesting to me that sex is so taboo amongst family members. However, sex is literally how families are created. I was looking at my Mom as a sexual figure in relation to her newly chosen partner (John), who isn’t my father, and myself as a sexual being in the eyes of my mother and stepfather.”

The series – which breaks with convention in both visual and narrative strategy – manifests as a psychological experiment born from constructed scenes that attempt to locate the edges of what’s comfortable. “As an only child, I’ve always had an extremely close bond with my mother. We are more like best friends than the typical dynamic. Because of this, it was slightly easier for me to ask her things. With my stepfather and father, it was different. I could tell they were uncomfortable with some things I asked them to do but were perhaps afraid to say no. Maybe saying no gave the taboo thoughts or discomfort more power.”

Despite photography being a public medium, Markle is not self-aware in front of the camera. She is deeply committed to her enquiry: to understand the intricacies of personal relationships and how they are coded in society. As an imagemaker, she defies the medium’s limitations as much as she disregards palatability.

Her photographs feel alive and dynamic despite being carefully choreographed to excavate the psychological. As Markle moves into the commercial and editorial space – she recently shot for the New York Times, New York Magazine and iD – her bold and defiant style raises the standard, breathing new life into risk-averse contexts.