Exposure: Thea Traff

Formerly a picture editor for the likes of the New Yorker and Time, Thea Traff now channels her knowledge into making her own distinctive images

Thea Traff never set out to become a photographer. After studying philosophy and studio art, she surreptitiously fell into photo editing through a mentorship programme at Getty Reportage. What followed was a series of high-profile photo editing positions at the New Yorker and Time Magazine that honed her craft as a visual storyteller and incidentally laid the foundations for a successful start as an imagemaker.

Like many photo editors, Traff spent years shaping our visual culture behind the scenes. While you may not be familiar with her name, you’ve certainly seen the images she produced. From viral stories on contemporary life and culture (including the iconic Cat Person by Elinor Carucci and dynamic images of Lizzo by Paola Kudacki) to critically acclaimed political reporting (the opioid crisis by Philip Montgomery and Davide Monteleone’s special report on Mexcian Migrants), Traff’s work as an editor is diverse and incisive. For years, she pushed the boundaries of editorial photography, creating engaging stories with mass appeal.

Despite her success, she boldly pivoted from commissioner to artist in 2019. “I had this strong urge to stop producing work from behind a desk and, instead, be the one making it out in the world,” Traff tells me from her home studio in New York. “I would get shoots back and started to feel that I would have approached it differently, or there was a missed opportunity in a particular story. That growing frustration just eventually bubbled over. It’s been three years, and while I occasionally take on photo editing jobs, this transition has been incredibly liberating. Developing my portfolio as a photographer is a lifelong endeavour. There are so many directions I want to explore, and this whole transition still feels very new.”

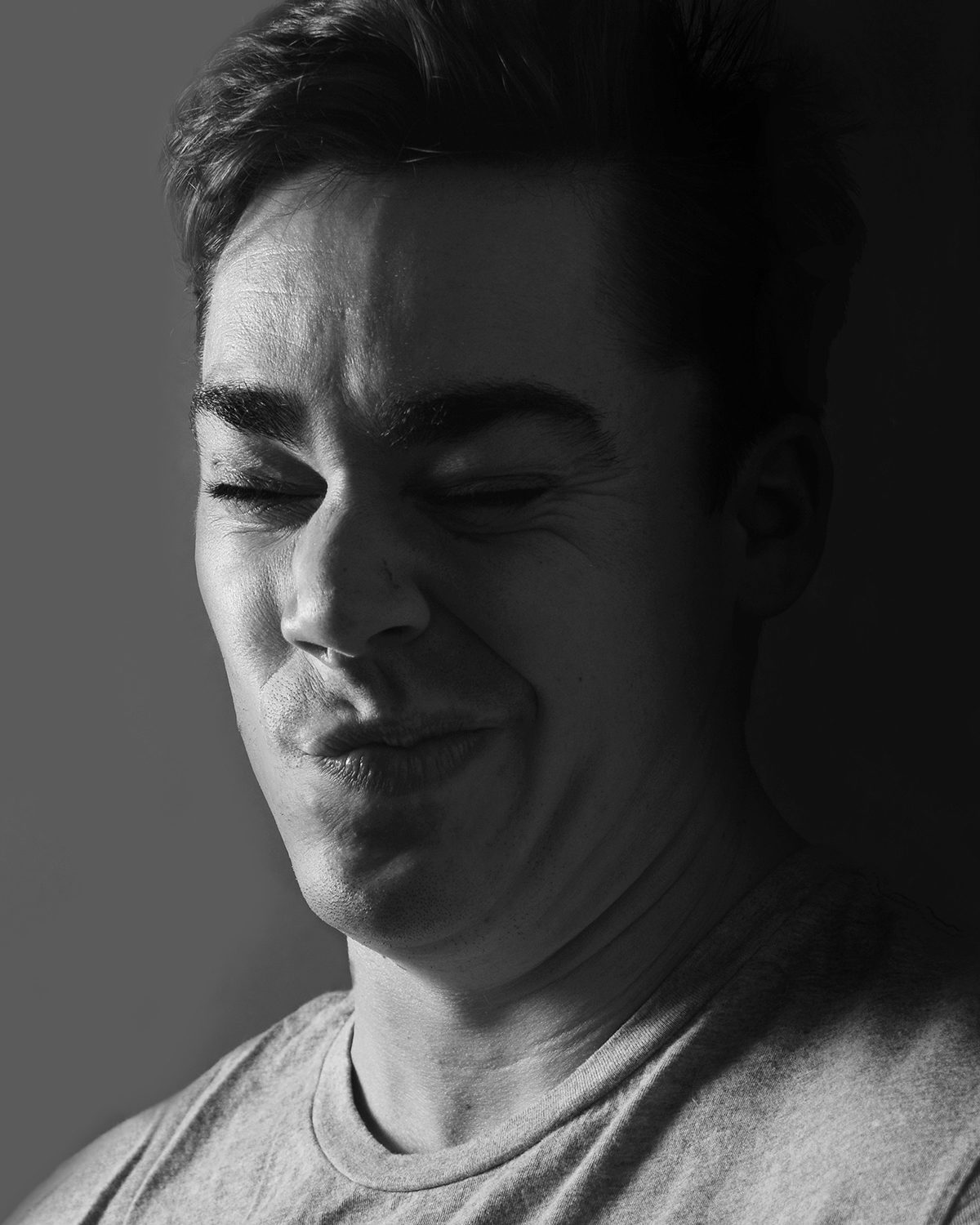

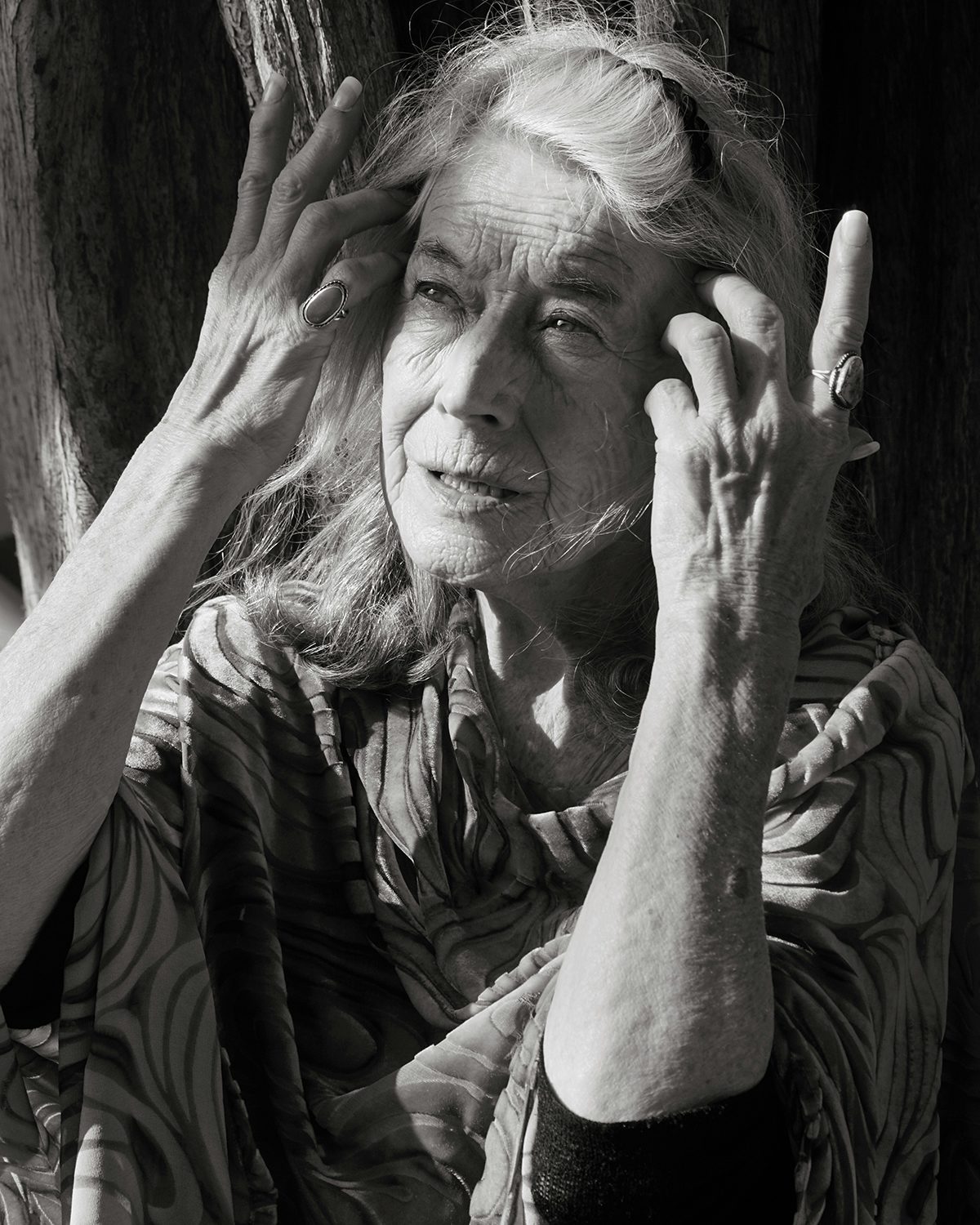

While Traff feels like she’s still breaking new ground, her portfolio tells a different story. She has the eye of a curious documentarian but is not distant or cold. Traff’s approach is the opposite: emotional, experimental, open and tender. Her images aim to turn the inside out, to create space for the fragile and often contradictory gamut of the human experience inside the frame. Black-and-white imagery is her current comfort zone, made distinct by the way Traff wields light to create impact and drama, leaving us with images reminiscent of old Hollywood or photo secessionists like Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, with a contemporary twist.

Traff’s signature — her unique ability to co-create moments of psychological and emotional complexity with her collaborators – is rooted in a desire to get away from the default ‘thousand-yard stare’, something she saw time and time again as an editor. This mission to be more expressive is also personal for Traff, who grew up feeling emotionally stifled. “I’m very introverted,” she explains. “Part of my desire to have my photography be emotionally driven is because it’s still hard for me to be super expressive out in the world. Channelling [my introversion] through my art feels like a healing way to have an emotional outlet.”

For Traff, centring emotion is not just about visual language; it’s also part of her mission. Emotion Cards is an ongoing personal project based around a deck of cards that seeks to help children learn emotions to process their feelings and more effectively communicate.

While several personal projects are in the works, it’s editorial where we’ve seen Traff make her most significant impact so far. Her sittings with the Rolling Stones, Claire Danes, Alexandra Daddario, Jessica Chastain, and the 2023 Tony nominees are just a few of the disarming assignments she’s worked on this year. Foregrounding interesting expressions and gestures, she offers something profoundly vulnerable for the viewer to connect with.

While Traff has worked hard to craft a distinctive approach and visual language, her commissioning experience has undoubtedly fast-tracked her career. “Being a photo editor informs every single decision I make as a photographer,” she explains. “Whether it’s practical skills — like knowing how to push a budget, or the variety of shots required — being on editorial staff is the perfect education for any aspiring photographer.”

Traff’s experience has also allowed her to build trust with editors quickly. “There’s no hand-holding or anyone breathing down my neck. I think they feel assured that with my experience, I know how to handle any situation. Which, for me, adds to my creative liberation. Enabling me to go out there and make the type of pictures I want to make.”

As we wrap our conversation, I ask Traff what she discovered about making impactful images as an editor and how that insight informs her practice. “I think everyone has their theories as to what that is, and every editor tries and push their agenda,” she says. “Some photo directors believe eye contact is essential.

“In contrast, others feel a voyeurist gaze, where you can look at a person without uncomfortable eye contact, creates a more effective connection. Whitney Johnson [Traff’s previous boss at the New Yorker] always tried to push photographers to capture an off moment. So, in making the unexpected, it would hold the audience’s attention more. I always try to keep that in mind. When the viewer encounters my work, I want them to look twice.”