Juju Stojanovic on moving from dance to design

Prior to studying design, Juju Stojanovic was building a career in dance, with a bit of maths thrown in. It turns out this is the perfect formula for her new vocation. She is part of our New Talent showcase for 2024

“To me, creating a visual piece of design feels like the same thing in my brain as playing with choreography and music,” says Juju Stojanovic, who took a rather unusual route to her design education, which began in 2021. Before studying design, Stojanovic was pursuing a professional career as a dancer with the San Diego Ballet. “Combining all that together with the logic and puzzle-solving of an education in maths I think results in a beautiful combination of skillsets to transfer to design.”

Stojanovic grew up in a Chinese-Serbian-American household and feels that this, combined with her varied education, has afforded her a “multifaceted identity”. Having danced since she was five years old, Stojanovic studied a double major in ballet and mathematics at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music in 2015. After graduating she accepted a full-time position in California and performed a repertoire of classical and contemporary ballets across the San Diego area and nationally.

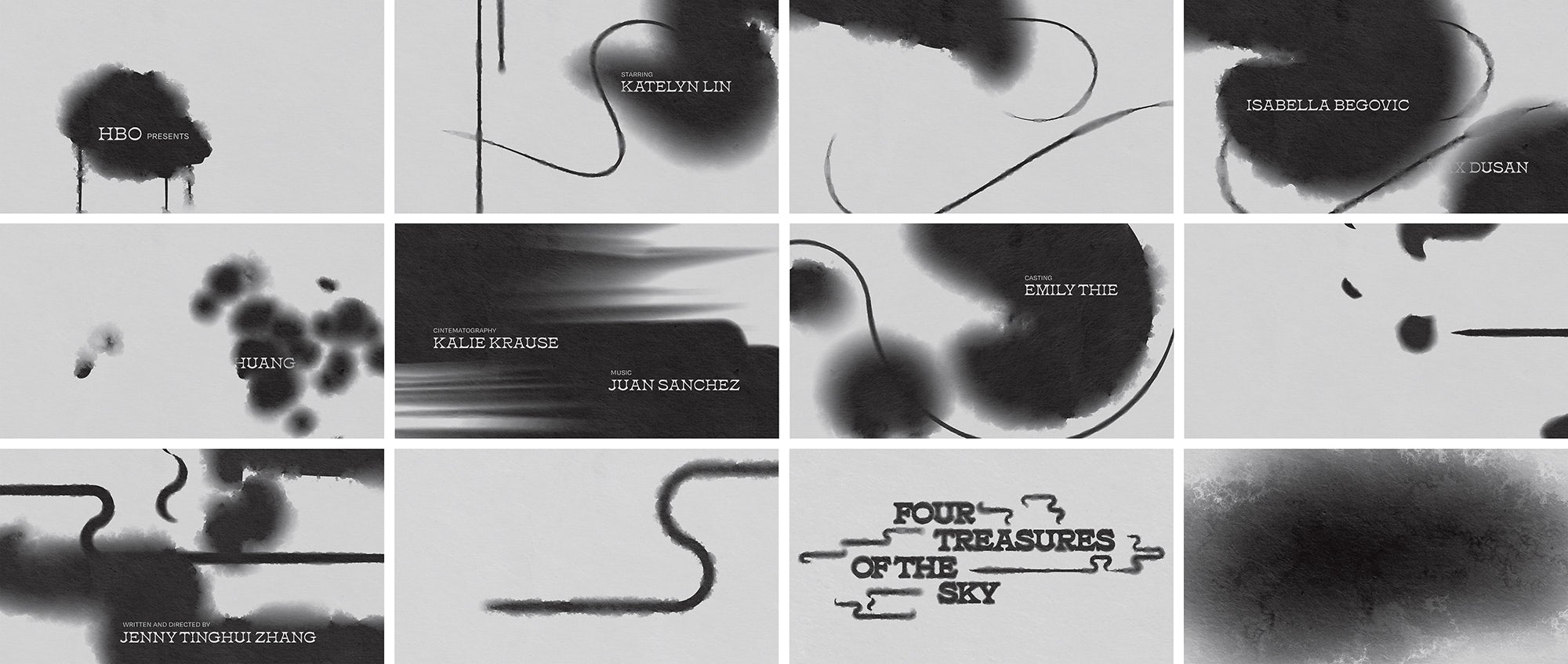

However, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Stojanovic says it became apparent that a career in dance was not sustainable – and she saw this moment as an opportunity to pursue her other passion. Currently in her fourth year at the University of Cincinnati College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning (DAAP), she has very quickly made a name for herself. An ambitious type designer, last year she received a Type Directors Club Young Ones award for a student lettering project.

“Design was not a choice that came out of nowhere,” she says. “I had an interest in art and design from a young age, and as I approached the end of high school, I was conflicted about whether I should go to school for ballet or design. An impactful art teacher in my final semester really tried to encourage me to pursue design, but I ultimately chose dance. I could always return to design but dance couldn’t wait. And while I had been fully immersed in dancing my entire life, design felt like something I had only dabbled in by comparison.”

Looking back, a career in dance isn’t as different from design as one might think. Both require “a keen sensitivity to detail, command of your audience’s eye, and creation of systems and visual language,” she explains. “As a dancer you’re trained to constantly be on high alert for details: ‘Does the angle of my head match that of the other dancers? Does the line created by my arm match the extension of line from my chin and eyes’ gaze?’ And any good piece of choreography creates a visual language for itself through considerations such as movement quality, form and concept, not at all a far leap from a design system,” she adds. “If nothing else, dancers and designers are both highly driven by a love for craft above all.”

Creating a visual piece of design feels like the same thing in my brain as playing with choreography and music

It was another inspiring teacher, professor Emily Verba Fischer at DAAP, who helped Stojanovic to see the aforementioned similarities between creating something visual and working with choreography and music. “It was like a switch flipped in my head,” she recalls. Verba Fischer was explaining the idea of applying the ‘golden ratio’ to time-based media and how it might be considered in temporal settings such as audio or video. For Stojanovic, dance has become a unique background to her design direction rather than an entirely separate endeavour. “Everything we do and have done informs our perspectives as designers,” she says. “I feel there is even a connection between the temporal rhythm and musicality of dancing with the visual rhythm and composition of a page.”

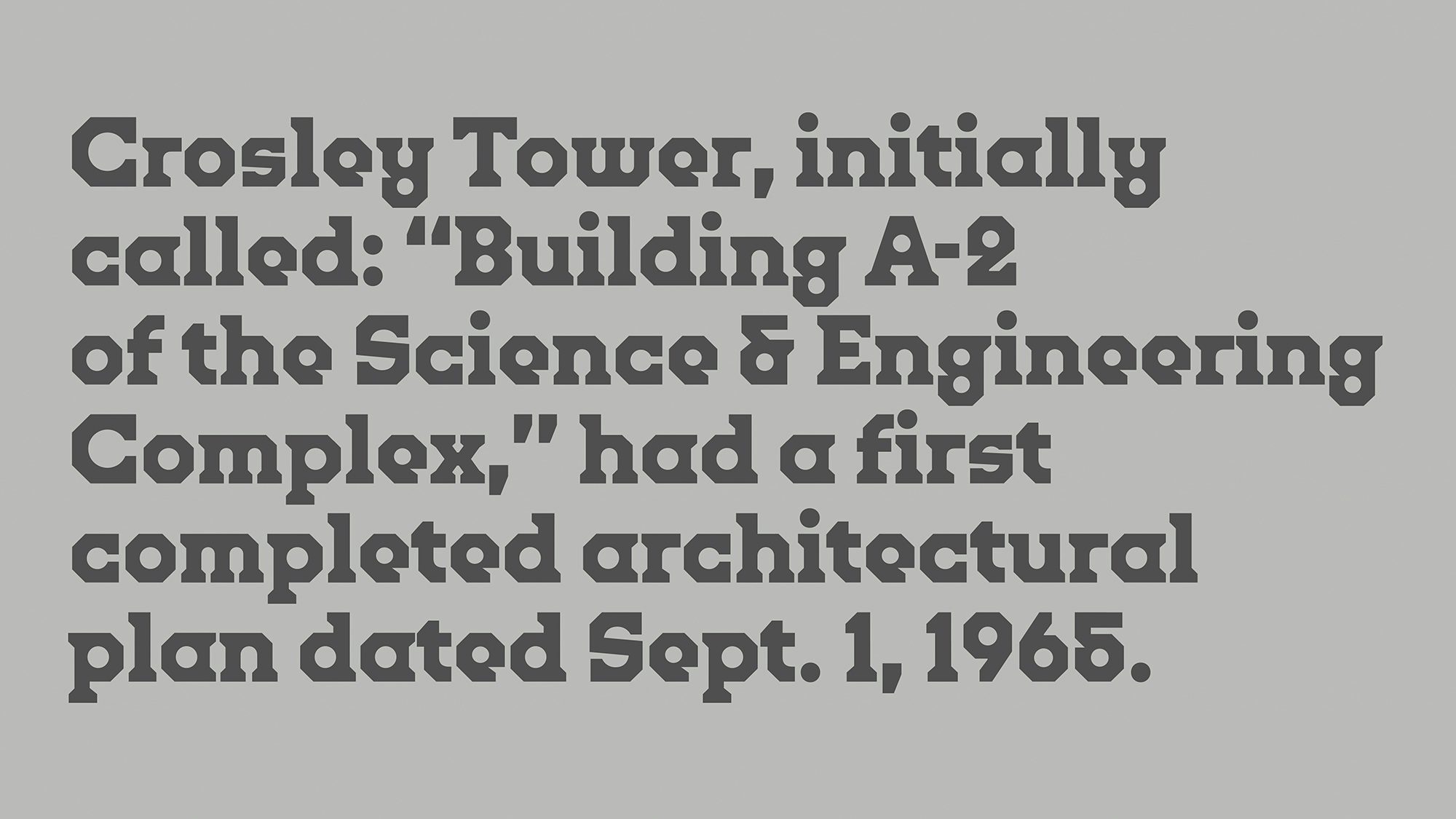

Internships are built into the curriculum at the design school at DAAP, and after a first year of foundation classes, the students alternate every four months between full-time school and full-time internships for four further years. Stojanovic now has three stints under her belt – including an internship at New York studio Order – with two more to go. While at Order, she was able to work on a personal project and designed her own display face, an ‘octic’ slab serif inspired by the Crosley Tower building at her university, “an equally loved and hated Brutalist landmark”, she says. She now plans to expand the character set and bring in other weights.

Type design is integral to Stojanovic’s work and her TDC award reflects her skill within the field. Her entry came out of a visual identity class, where the students were asked to redesign the identity for Aspen Music Festival and School, an annual classical music festival and summer school that takes place in the Rocky Mountains. Her solution saw the design and programming of an audio-responsive wordmark that made use of variable font technology and p5.js code.

“Referencing music notation, the mountainous environment of the festival and the movement of an orchestra itself, the letters react live to music input and mimic even the raw vibrato of the instruments,” she explains. “It was one of the most challenging and rewarding projects I’ve done so far. It really felt like the moment that I came to fully appreciate my ‘unconventional’ backgrounds, as they all assembled to accomplish something that wouldn’t have been possible if I had gone straight into design without my prior experiences in dance and maths.”

For Stojanovic, inventive type has been intertwined with digital technology since her childhood obsession with Google Doodles in the early 2000s. “I used to save each one in a Word doc on my family’s computer,” she recalls. “I was fascinated by how you could imply written language through other visual forms and thereby express ideas greater than the individual letters themselves.”

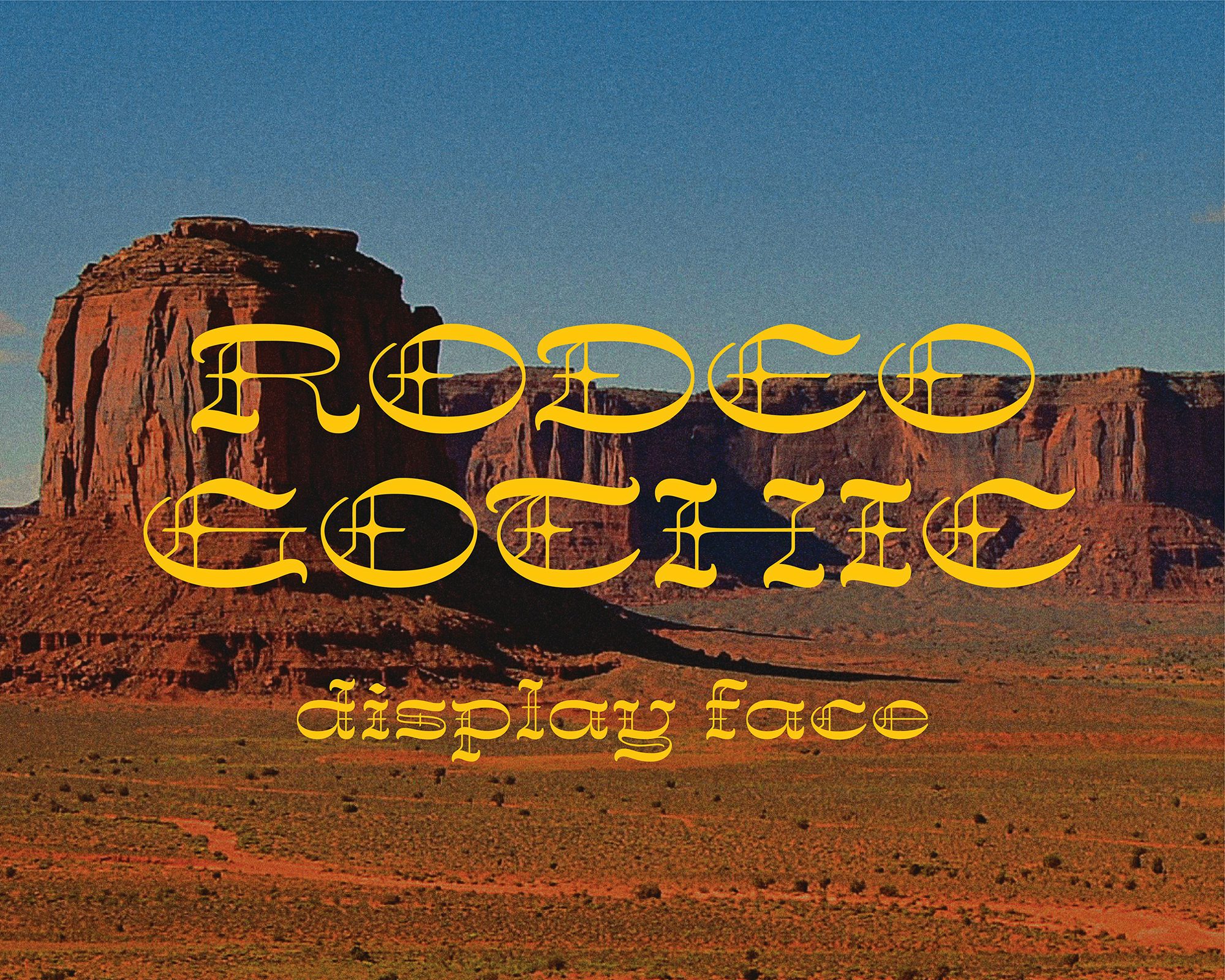

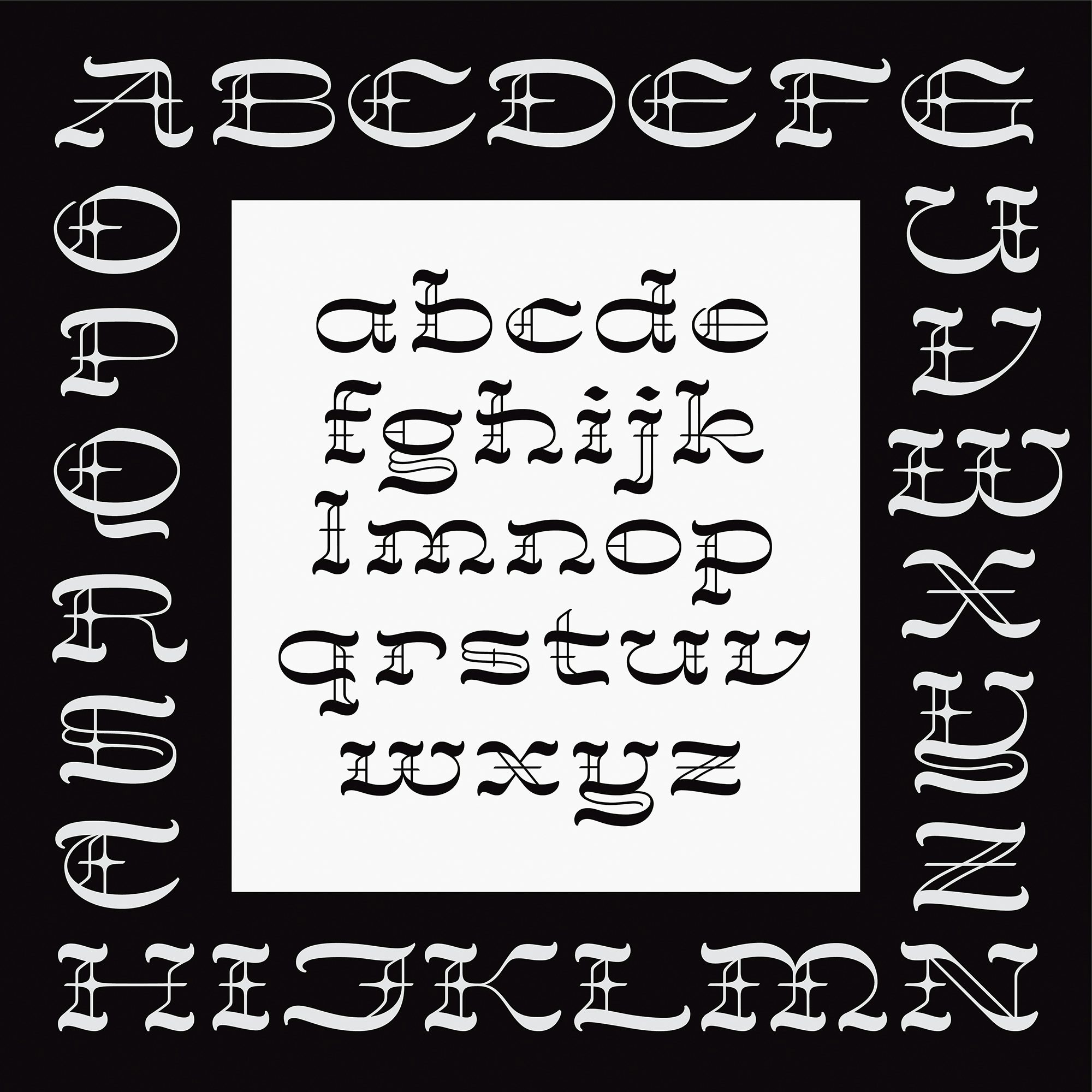

After a ten-week course on display type, Stojanovic now also has her first typeface completed. An expressive display face, Rodeo Gothic is “a mash-up of Western and Blackletter type. I like to say it’s a little ‘Ye Olde’ and a little ‘Yeehaw’,” she says. “It’s not super modular, it doesn’t have many straight lines, and it required a lot of back and forth between sketch and vector.”

Despite her leaning towards tech, on her website Stojanovic has included some initial sketches for the Aspen work that were done on paper. “As a student, I am still figuring out my process, but I do always start through analogue sketches, and I think I always will,” she says.

AI fills in the blanks. But the blanks are important. And what are we left with when we strip something like design of its decision-making?

“For me it is the most natural and direct way to translate initial ideas and concepts from my head into something visual in front of me. Even with coding, I can think much more clearly if I roughly sketch what I’m trying to accomplish and even do some quick paper calculations and diagrams to really understand what’s happening.” As a designer who readily admits she occasionally lets perfectionism get the better of her, analogue sketching also forces her to begin projects a little looser.

The ‘process’ of translating ideas from her head to her sketchpad is also important, and while she is well aware of the impact of AI on design, it’s an area that, like many practitioners, she views with some concern. “I think my biggest caution with AI in creative work is the loss of intent,” she says. “As designers our work involves a constant stream of decision-making. What AI does is eliminate the number of decisions we have to make. It fills in the blanks. But the blanks are important. And what are we left with when we strip something like design of its decision-making? I would love to see a future where we can use AI healthily, ethically and responsibly, but I see our ability and freedom to make these decisions as a great privilege. It’s what this profession is all about.”

The continual guidance that Stojanovic has received within dance and design alike has meant she has no regrets about where she is now. “Thanks to a few important voices over the years, including the high school art teacher that pushed me so much, I just had a gut feeling that I had to go for it,” she says. “Now that I’m a few years in, returning to school for design really has felt like one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.”

So what of her post-grad plans? “I actually would like to teach eventually after I work in the industry for a period of time,” she says. “I think you can tell by all the teachers I’ve mentioned that, ever since childhood, my teachers have always been some of the people I look up to the most. I’d love to be able to give back to future students like so many of my teachers over the years have impacted me.”