Jack Zhang’s new nostalgia

Barely graduated, animation director Jack Zhang has already worked with some of the biggest names in fashion and music. Part of our New Talent showcase for 2024, he tells us about his journey so far

In the streaming era of crystal-clear images and AI tools, it seems the antidotal charm of pre-2000s anime is hitting all the right notes with Gen Z. And brands are taking notice. “A lot of the briefs I receive include screengrabs that I can tell come from a City Pop video,” says animator Jack Zhang from his shared east London studio space. “Or a lo-fi Vaporwave one.”

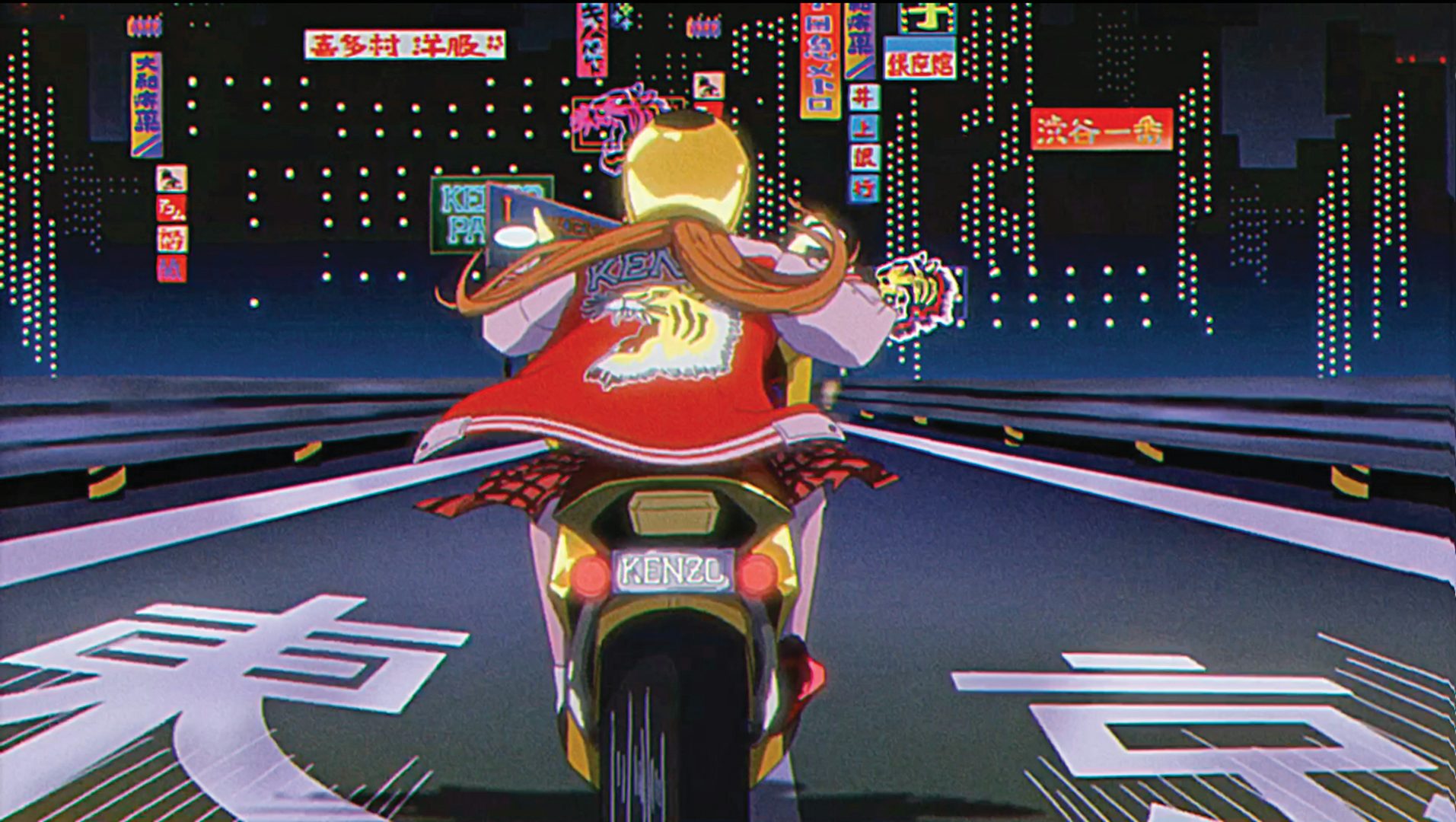

Fan uploads of pop music from 1980s Japan have reignited interest in the period’s retro-futurist sensibilities. In tribute to the era’s home video boom and the country’s subsequent golden age of animation, the songs are accompanied by its prototypical images: a hypnotic blend of cyberpunk cityscapes and vintage haze, to which Zhang’s images pay loving homage.

Growing up in China in the early 2000s, classic anime evoked in him a confusing feeling that remains to this day: like nostalgia, but for a time before he was even born. It formed the backdrop to his unorthodox upbringing. The oldest of three, he was “the guinea pig” in his artist father’s experiment of taking his children out of school and letting them learn at home, at their own pace. At the time, unsupervised in front of the TV with a sketchpad, he thought, “Oh my god, I’m just wasting time. I’m going to end up nowhere.”

Looking back now, the hours of passive study gave birth to this signature style. Their influence is plain to see in his 2D animations which, just three years after graduating from University of Arts London, he has produced for the likes of MTV, luxury fashion house Kenzo, and pop stars Coldplay, Ariana Grande and Troye Sivan.

Considering anime’s worldwide appeal and the internet’s globalising impact, it’s not surprising that American, French, British and Australian clients are adopting the style in the hope of captivating their youth audience. But the trend does throw up questions around cultural appropriation. Zhang feels it’s more appreciation and that, frankly, people can be a little too traditionalist in this area.

On social media, though, he recently found himself at the receiving end of a backlash against his mixing of Chinese iconography with his Japanese-inflected style, accused of corrupting and fetishising his culture. He pays it no mind, welcoming the extreme emotions his work elicits. “I’d rather that than have people look at it and not feel anything,” he says. For him, it’s just about creating something beautiful.

There are layers to how Zhang goes about doing that, adopting techniques from Japan’s tra-digital era, when computers were still mainly enhancing practical techniques. They belie the fact that he produces his work entirely digitally, in TVPaint.

His cel-animated look takes from the traditional process of hand-painting foregrounds and backgrounds separately on acetate sheets, which are overlaid and manually photographed. Its painstaking nature created shortcuts that became staples of the medium and appear in Zhang’s work: a set of frames are sequenced for one continuous loop; high-contrast urban landscapes suggest detail on the horizon with just a few stipples.

Cementing the retro feel is his perfect recreation of the desaturating fuzz of analogue. Zhang’s edges fray, his colours blow out in an unmistakably home video way. It’s an effect that is stretched almost to the point of parody by Vaporwave, a subgenre of music videos that exaggerate the City Pop aesthetic and the psychedelic beauty of decaying magnetic tape.

That we are intangibly drawn to it is surely the latest manifestation of our love affair with physical media. Vinyl sales are up, filmmakers are returning to celluloid film, even cassettes are back in vogue.

The trend suggests that we yearn for a disappearing sense of tangibility and reverence, something that exists not just on a server somewhere but actually bears the signs of a long and celebrated shelf-life. Unlike now, when things get immediately lost to the scroll.

“That’s why I’m not on TikTok,” says Zhang. “I don’t want my content being looked at for [only] two seconds.” Things are only marginally better on Instagram, where Zhang posts and receives most of his work, but the app’s new iteration as Meta’s AI training ground poses a disruptive threat to the industry. “Let’s be real, it’s worrying isn’t it?”

AI has already made its way into two of his projects for the music industry. Both times, it was admittedly helpful in reducing the preliminary back and forth between him and the client.

But what troubles him is the pervading argument that machine learning is here to save animators from their hard, everyday labour. What it doesn’t consider is that however tedious the work, people rely on it. Animation is a trade – steady pay cheques and entry-level jobs are essential.

So far, though, Zhang feels lucky to have worked with collaborators who respect when AI is helpful and when it is insulting. The balance did once tip, when a dozen rounds of edits to capture a pop star’s likeness ended in them sending him an AI-generated version they preferred. But overall, “as long as you don’t put AI out as your final work”, bypassing the artist entirely, “then I think it’s fine”, he says.

Zhang hopes that if he keeps pushing forward, he can hold on to a style that transcends AI’s abilities as essentially an imitator of what already exists. Ultimately, though, it’s up to those commissioning artists to keep valuing human collaboration.

“It takes a real client to understand it,” he says. “The sense of satisfaction that comes from dedicating ourselves to the project just can’t be derived from typing in a couple of keywords.” It takes a flesh-and-blood connection to extract what’s unique about the brief and make images that might speak to the past but are imbued with something entirely new.