Carlos Idun-Tawiah on breathing life into the past

The photographer weaves reality and fiction in his work until the two become blurred. Here, he talks to us about his process and maintaining creative integrity in commercial projects

“Isn’t it interesting?” says Carlos Idun-Tawiah. “Forms like poetry, painting, and even film are given room for fiction. But then photography has sort of been caged to a real-life documentation of what is, where we are not able to speak about what could be or what could have been.”

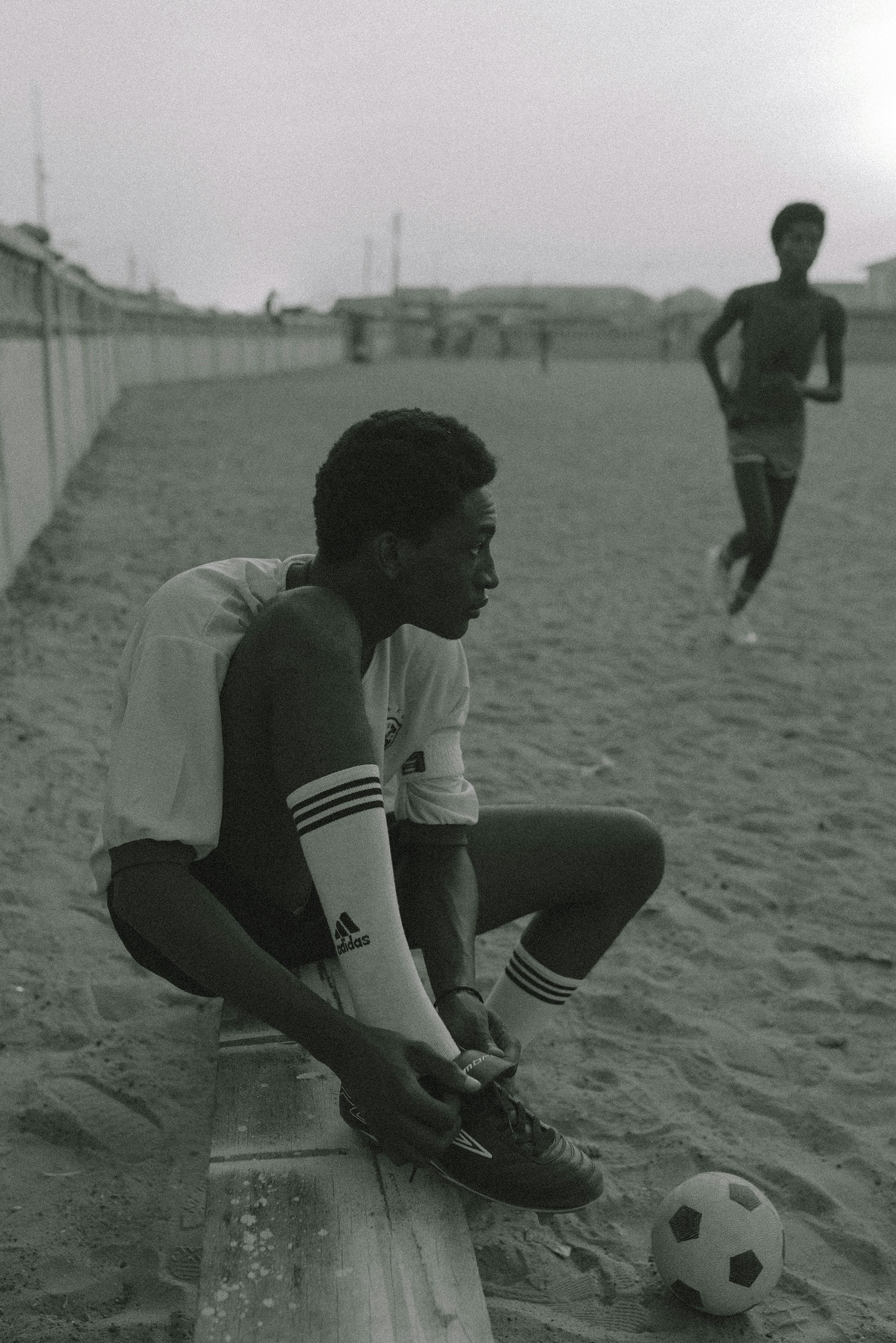

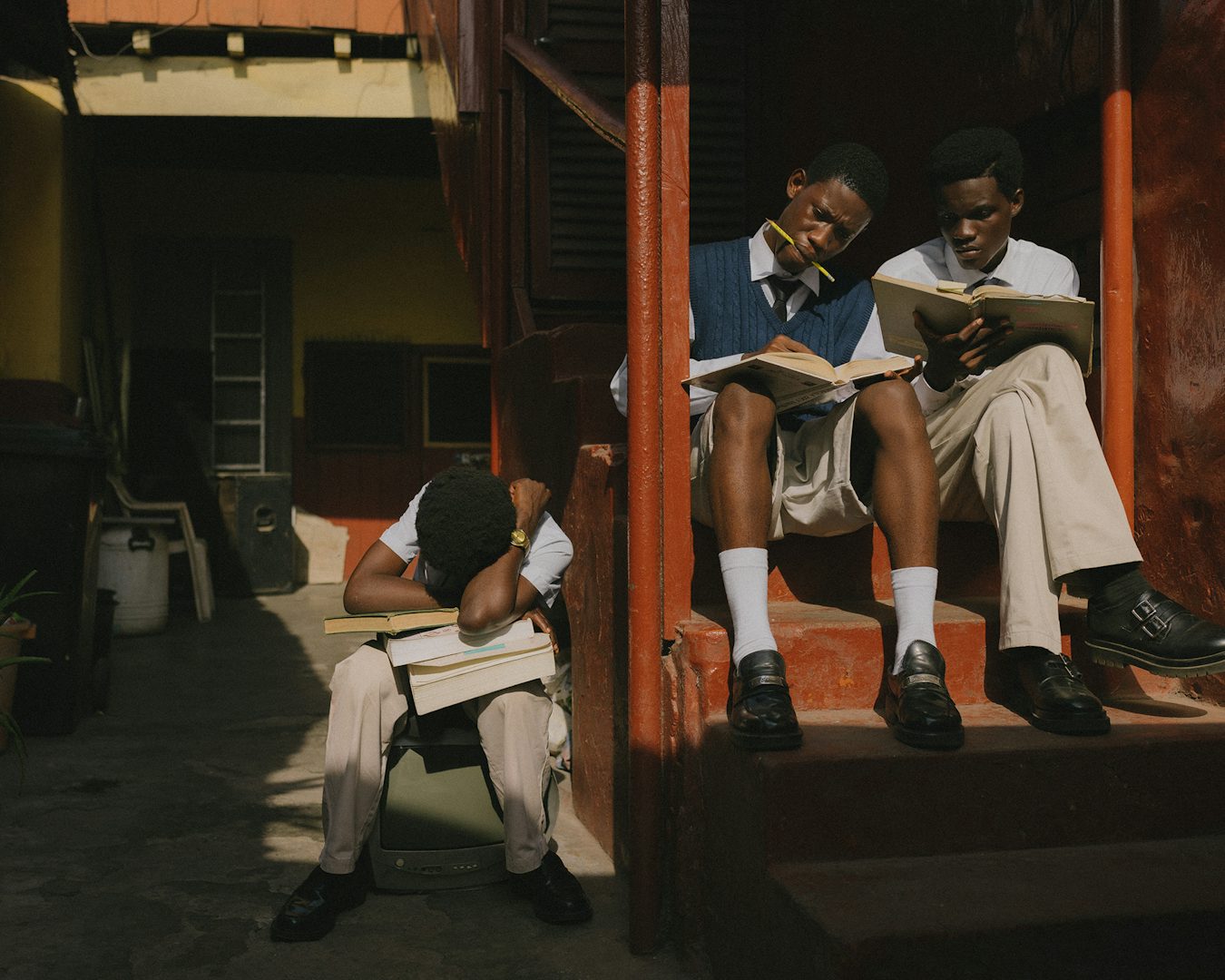

Through his carefully staged images, the Accra-based photographer and director taps into the hidden recesses of individual and collective memory. His tender series Boys Will Always Be Boys shows men of all ages forming bonds – even if unspoken – in the barbershop, the classroom, or the boxing gym.

Elsewhere, Sunday Special, a more autobiographical body of work, mirrors his own family albums filled with photos of him and his loved ones at church. Although the shoots are pre-planned, his scenes feel naturalistic, even familiar, and that’s exactly the point.

Idun-Tawiah has cultivated a body of work that’s bound up in nostalgia, history, and memory: traits that informed his instinct to be a photographer. Pictures became a way for his father, who lived in London for most of the year, to shrink the geographical gulf between himself and his children as they were growing up in Ghana.

When Idun-Tawiah was planning to study in the US, his father bought a DSLR for him so he could document a community project to support his scholarship application. His father died before he could give the camera to him. “It was a bundle of emotions … because I didn’t know whether to be excited about it or to be sad that he wasn’t here to see me use it.”

Forms like poetry, painting, and even film are given room for fiction. But photography has been caged to a real-life documentation of what is

This connection to memories is the beating heart of Idun-Tawiah’s work, but so too are the hypothetical ‘what ifs’ that a life cut short often forces you to consider. It’s as much about plotting lived histories as it is visualising imagined futures, and in both, staging and fiction are integral to bringing us closer to a truthful image – though truth is itself an amorphous concept.

“What is fiction anyway? And where do we draw the line between fiction and non-fiction? Because expressionism is subjective and ultimately boils down to our personal interpretation of reality and how we choose to convey our individual understandings of things,” he says.

This use of staging to illustrate the past is partly a reflection on life as a sprawling, interconnected network, where tweaking one cog in the system might have produced an alternative pathway. It’s this idea “that every action, every single second, and every single decision you make correlates to a bigger experience that might not just affect you but affects the world as a whole,” he says.

The historic cues in his work also paint a picture of the past that’s rarely seen in photography archives. He explains that not many people could afford to have their photo taken. If they could, they were likely studio portraits, but even these were mostly reserved for special occasions. “So it’s also my own way of going back to fill the gaps in the archives and imagining instances that I didn’t see much of in the canons: people enjoying the mundane pleasures of life, or seeing Black people at leisure,” he says.

For Idun-Tawiah, fictionalised images can be a “conduit for change, where my audience could see these optimistic possibilities of life as inspiration to realise a more hopeful world for themselves and for generations to come”. Although biopics are commonplace in filmmaking, he wants to see the same creative licence given to still imagery.

His “bridge” to the past is multidirectional. Artists and documentarians who were especially prolific in the 20th century have informed his practice: Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, James Barnor, Roy DeCarava, Carrie Mae Weems. Yet it’s not just about being inspired, he says. It’s about creating a dialogue with their images and examining the conditions around how and why they were made.

With a growing number of accolades under his belt, including winning entries at Belfast Photo Festival and OpenWalls Arles in 2023, more brands will inevitably come his way. Yet Idun-Tawiah is set on bringing the same intentional and deeply personal quality to commercial projects.

Photography is my way of going back to fill gaps in the archives: people enjoying the mundane pleasures of life or seeing Black people at leisure

He is mindful that commissions are more likely to involve compromises, “regardless of what the company says about creative control and whatnot”, he explains. “It will always be a battle among creatives, among artists, to follow what’s hot and what’s trendy.”

It’s why it’s important to him to find the right opportunities that gel with the rest of his output and resist morphing to suit trends. “I think it’s all about extending your personal work, which I believe would be your most sincere work,” Idun-Tawiah says. “Trying to overlay that or communicate commercial work through that same language is the most prudent thing you want to do as an artist.”

Samuel Fosso, the French-Cameroonian photographer known for his experimental self-portraits, lays down a particularly valuable blueprint here. His branded projects have managed to blend seamlessly with the rest of his work, particularly his 1997 series Tati – a commission from the French department store of the same name, which ended up becoming one of his most revered artistic bodies of work. More than anything, Idun-Tawiah admires Fosso’s resolve to pursue his calling as an artist, despite being largely underappreciated for decades.

“He was making self-portraits at a time where African self-portraiture didn’t have a real audience to consume the work. But then he made these photographs for so many years and the world now looks at the work and is in utter awe, because there was this guy that decided to believe that self-portraiture had an audience.

“He was probably just ahead of his time, but he still believed in that so much that when the world was ready, he had already made the work. That’s one thing that inspires me to keep doing what I’m doing, regardless what the numbers look like and what the charts are saying.”