Arturo Soto on memory, personal history and the politics of place

In his book Border Documents, the photographer and writer draws on his father’s anecdotes and his own images to challenge preconceptions of the Mexico-US border

“Every first kiss had to happen somewhere,” reflects photographer and writer Arturo Soto. “Mapping memory onto geography is something we all do constantly, albeit in intangible ways. I want to create a body of work that highlights the emotional dimension of urban environments.”

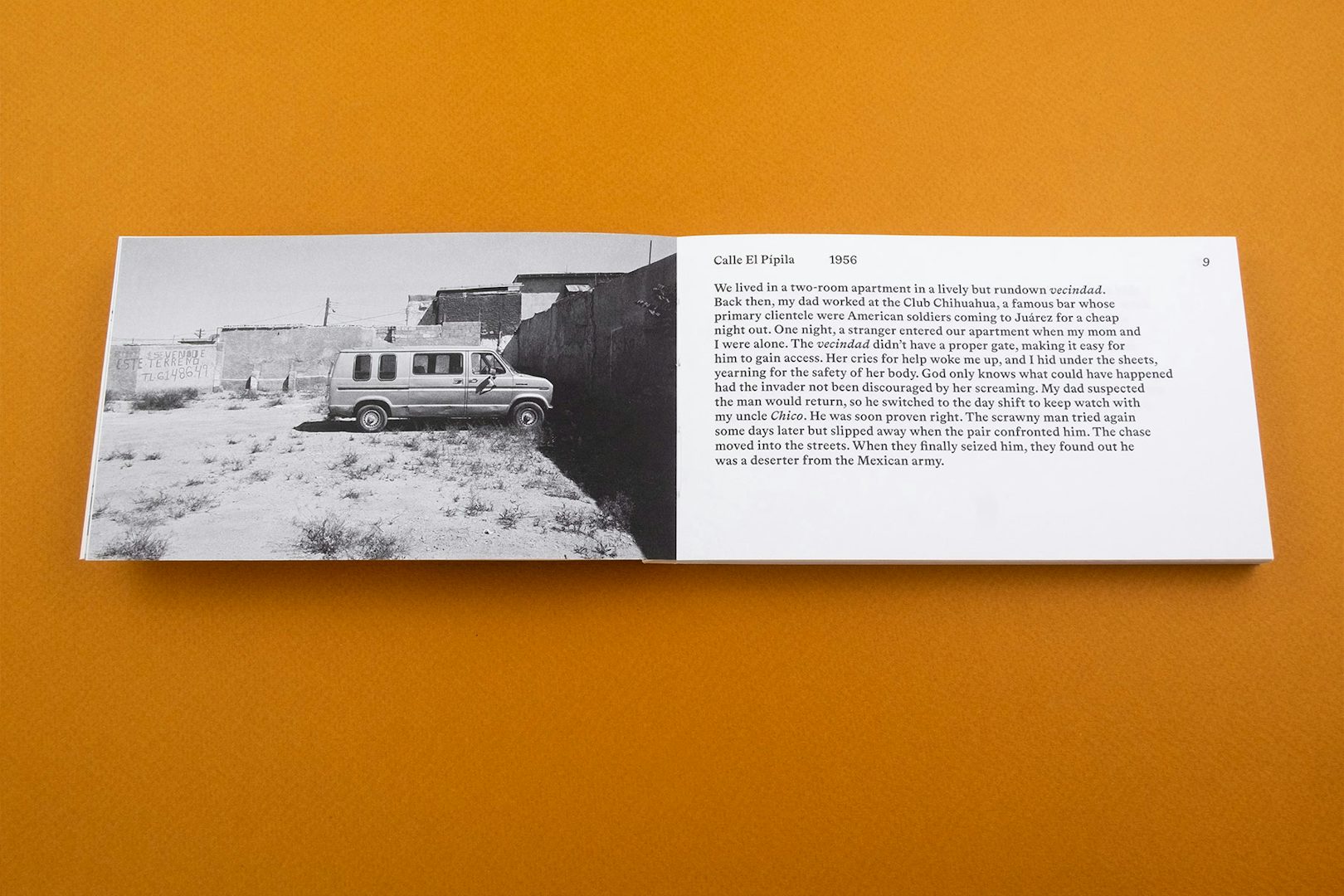

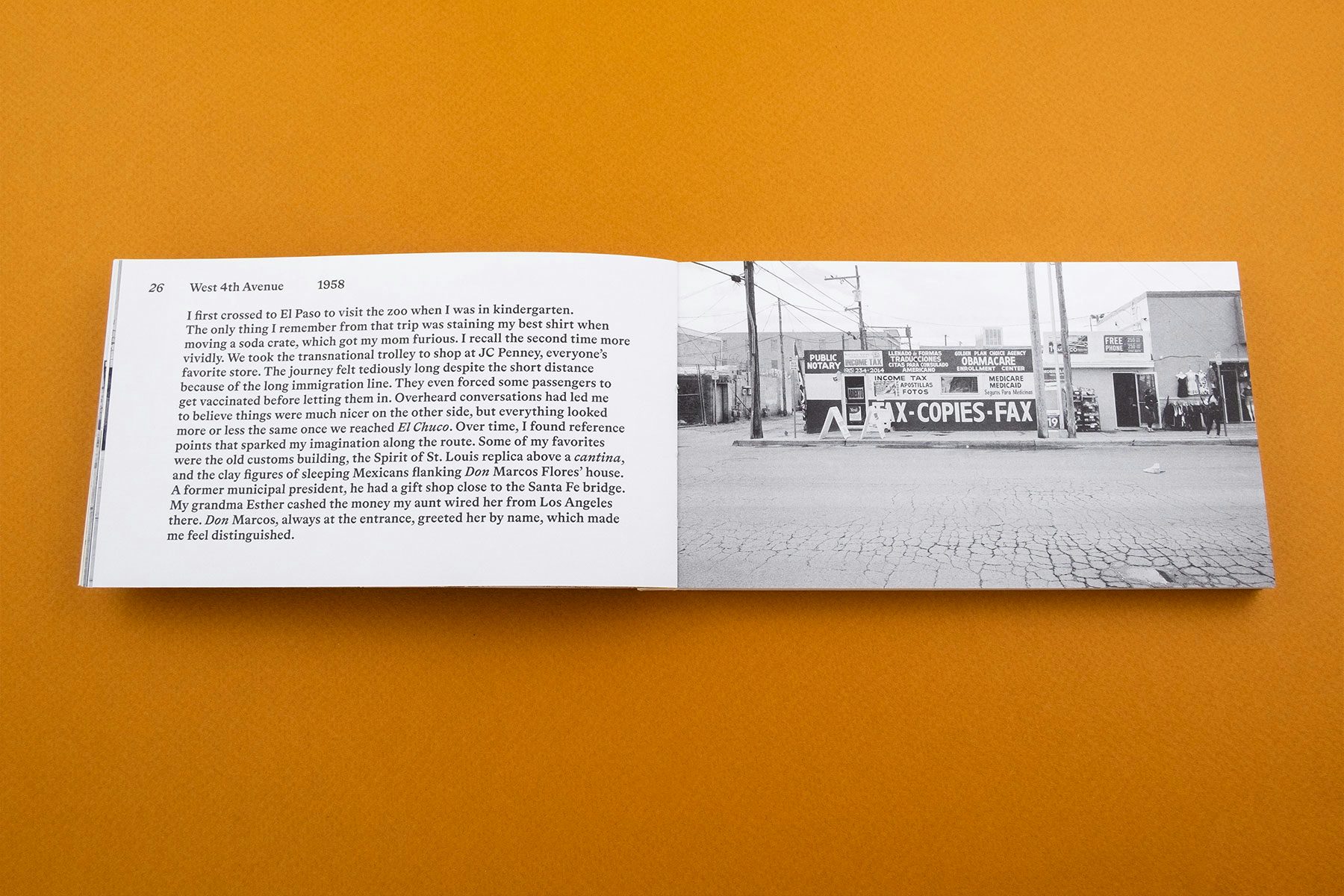

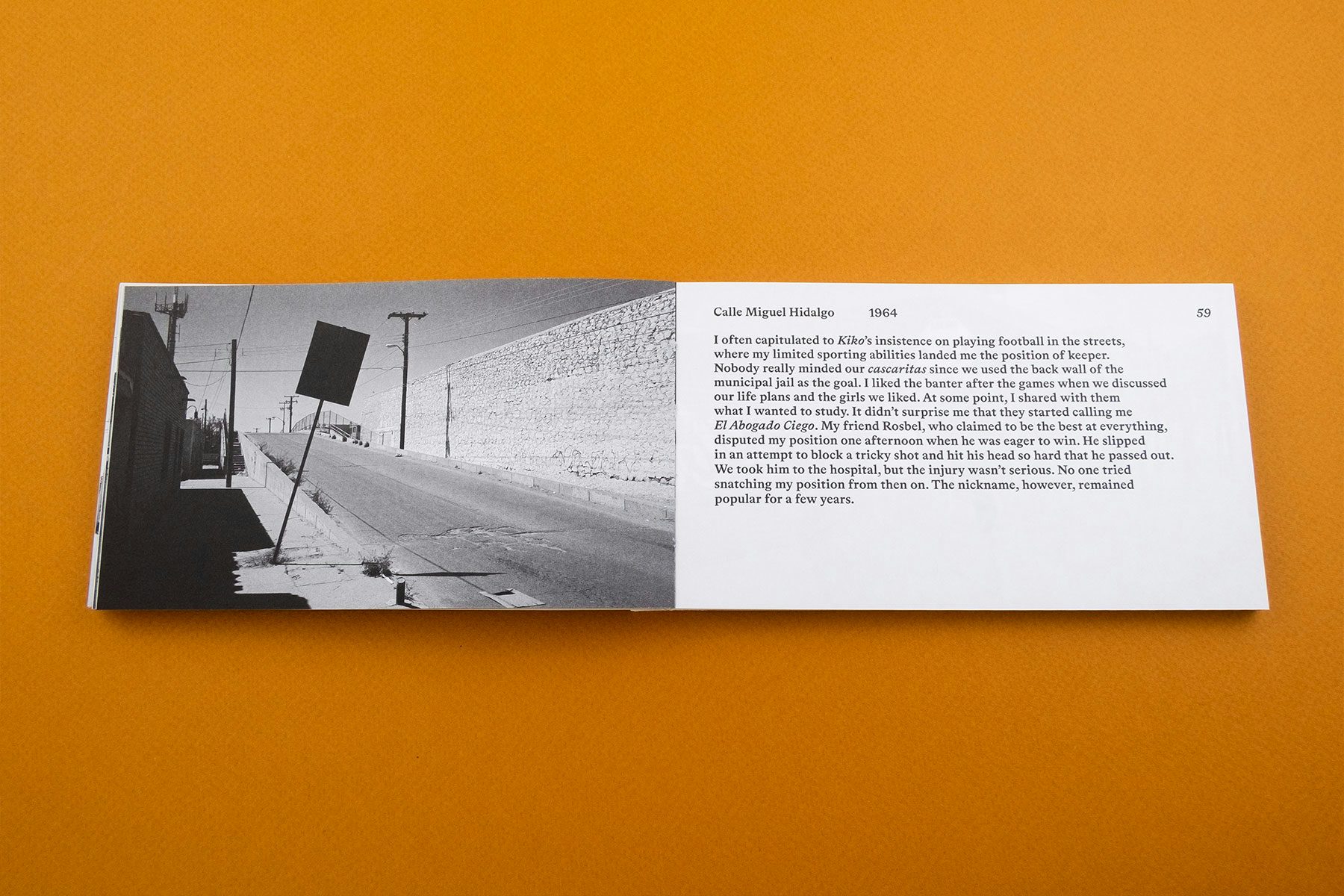

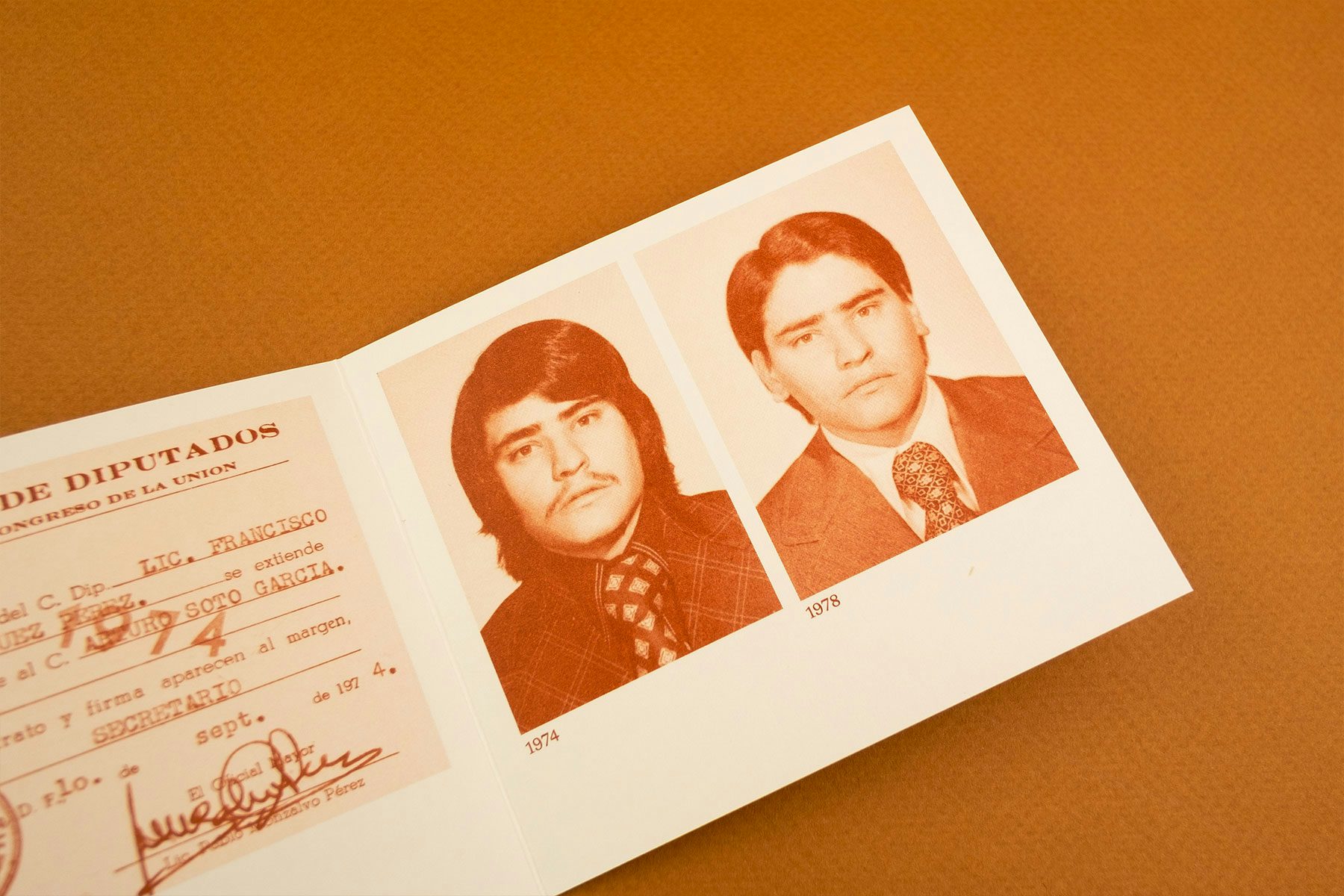

With his latest book, Border Documents, Soto pairs his father’s recollections of life on the US-Mexico border with his own images of neighbouring cities Ciudad Juárez and El Paso. Part memoir, part political study, it’s a disarmingly profound work that asks what happens when personal stories are laid against one of the world’s most contested frontiers.

The book’s origins lie in the stories Soto grew up hearing at home. His father’s repertoire of anecdotes – some comic, some harrowing, all steeped in the texture of border life – formed the foundation of the project. But turning oral tradition into written text was not a straightforward task. “I had heard most of the stories since I was little,” Soto recalls. “The first step was to identify those that had a personal, sociopolitical and spatial dimension.”

Collecting them involved long conversations, first in person and later via FaceTime. Sometimes crucial details surfaced only on the tenth or twelfth retelling. Other times, his father’s instinct to embellish or blend several episodes together forced Soto into the role of editor, distilling sprawling narratives into sharply honed vignettes. “Getting them on paper was tricky,” he admits, “but finding the right tone was essential.”

For Soto, the next step was to place these memories into dialogue with photography. This decision grew out of his doctoral research at the University of Oxford, which explored how text shapes photographic meaning. The influence of artists such as Moyra Davey and Chris Verene looms large: Davey’s insistence that photographs might “take seed in words”, and Verene’s experiments with captions that stretch the space between text and image.

It’s become such a cliché to focus almost solely on the drug trade and illegal immigration. Other stories can’t break through the barrier of prejudices established by the media

Soto wanted to inhabit that in-between zone, showing how words and pictures can unsettle as much as they inform. “People tend to think of texts in relation to photographs as fixers of meaning,” he explains. “But words carry their own ambiguity. Combining these two media can open up possibilities of interpretation rather than delimiting them.”

If memory is unreliable and fragmentary, photography is often assumed to be the opposite: objective, evidentiary, neutral. Soto saw an opportunity in the clash between these registers. By juxtaposing his father’s recollections with images of the border as it appears today, he created a third layer of meaning – one that arises not from either medium in isolation, but from the tension between them.

“Perhaps the keyword is ‘fragmentary’,” he reflects. “Border Documents is neither a comprehensive portrait of my father nor of these two cities. It merely proposes, via these vignettes, that the political and historical idiosyncrasies of the border are intertwined with the personal lives of its inhabitants.”

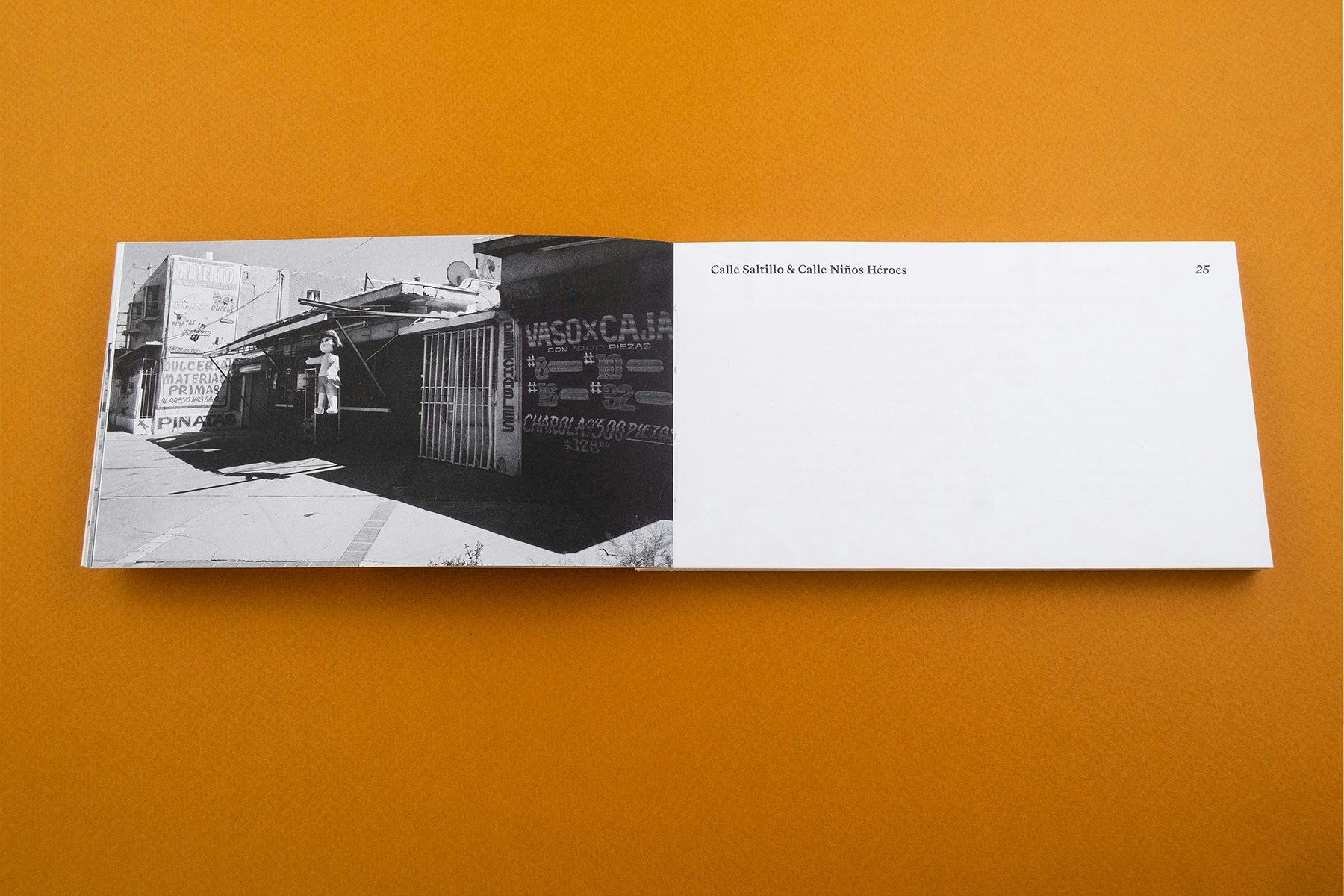

The sequencing of the book reflects this logic of interweaving. The narrative is structured chronologically, tracing the arc of his father’s life. But design choices sharpen the conceptual underpinnings: images of Ciudad Juárez always sit on the left-hand spread, while El Paso occupies the right, mirroring the physical relationship of the two cities while creating a visual rhythm across the book.

The making of the book was not without its practical challenges. Soto was living in the UK during much of its production, which meant his time photographing in Mexico and the US was brief and pressured. Capturing scenes in the harsh desert light demanded precision.

Beyond technical considerations, there was also the problem of accessibility: how to ensure his father’s stories spoke not only to those steeped in border history, but also to international readers with little knowledge of the region. That meant carefully negotiating language, avoiding colloquialisms that might not translate, and paring back the prose without diluting its emotional charge.

For all its specificity, Border Documents is representative of Soto’s broader practice, which consistently probes the relationship between text and image. His previous book, A Certain Logic of Expectations, used a similar strategy to reframe Oxford. Where that project dissected the cultural codes of a historic British city, Border Documents grounds itself in an ever-shifting space marked by stereotypes of violence, drugs and migration.

Against this backdrop, Soto insists on the possibility of other stories, ones that make visible the rhythms of everyday life. “It’s become such a cliché to focus almost solely on the drug trade and illegal immigration,” he says. “Other stories can’t break through the barrier of prejudices established by the media. Whenever we see images of a conflict zone, we should remind ourselves that there are many different kinds of people there, each with their own lives and corresponding rhythms.”

Art can be the means by which we recoup stories from the contempt of history

Ultimately, Soto is less interested in providing a definitive account of the border than opening up a more nuanced conversation about it. His work acknowledges the slipperiness of both memory and photography while showing how, together, they can deepen rather than diminish meaning.

As a result, the book resists both the flattening clichés of mass media and the rigid binaries of border politics. It gestures instead toward a more expansive idea of place, one in which personal narrative, cultural history and geography are inextricably linked. “Art,” suggests Soto, “can be the means by which we recoup stories from the contempt of history.”

In Border Documents, those stories have found a form that is at once intimate and universal – a cartography of memory traced across a landscape too often reduced to sensationalist headlines.

Border Documents is available via The Eriskay Connection; eriskayconnection.com