Are creatives undervaluing themselves?

Jelly’s global head of artist management Nicki Field, How&How founder Cat How, and photographer Jackson Bowley share advice on knowing your worth and how that translates into getting paid fairly

People don’t like talking about money. While it’s something we all inevitably need to live, knowing your worth in the context of the world of work is largely viewed as a murky topic that makes many of us clam up. The creative industries is no exception to this, having historically relied on the idea that creatives should be grateful to be doing something they enjoy, rather than be appropriately paid. This lack of transparency has a knock-on effect when it comes to figuring out what you should be earning, particularly early on in a creative career.

As Jelly’s joint MD and global head of artist management, Nicki Field has witnessed the money dilemmas that many illustrators, animators and other commercial artists go through first hand. While she acknowledges that there are more financial resources available for creatives than there used to be, she suggests that it’s becoming increasingly challenging for those who aren’t in the know to get paid fairly.

“I feel like as the cash has fallen out of the industry, there’s a prevailing sense of a race to the bottom and the value hasn’t upheld,” she says. “Because creativity at large is so undervalued, I believe as a community we have a responsibility to share that information and knowledge more widely so that people can have more access to the tools that they need to learn how to value themselves correctly, because it’s just a Wild West. The antidote to that is transparency and visibility on realistic fees.”

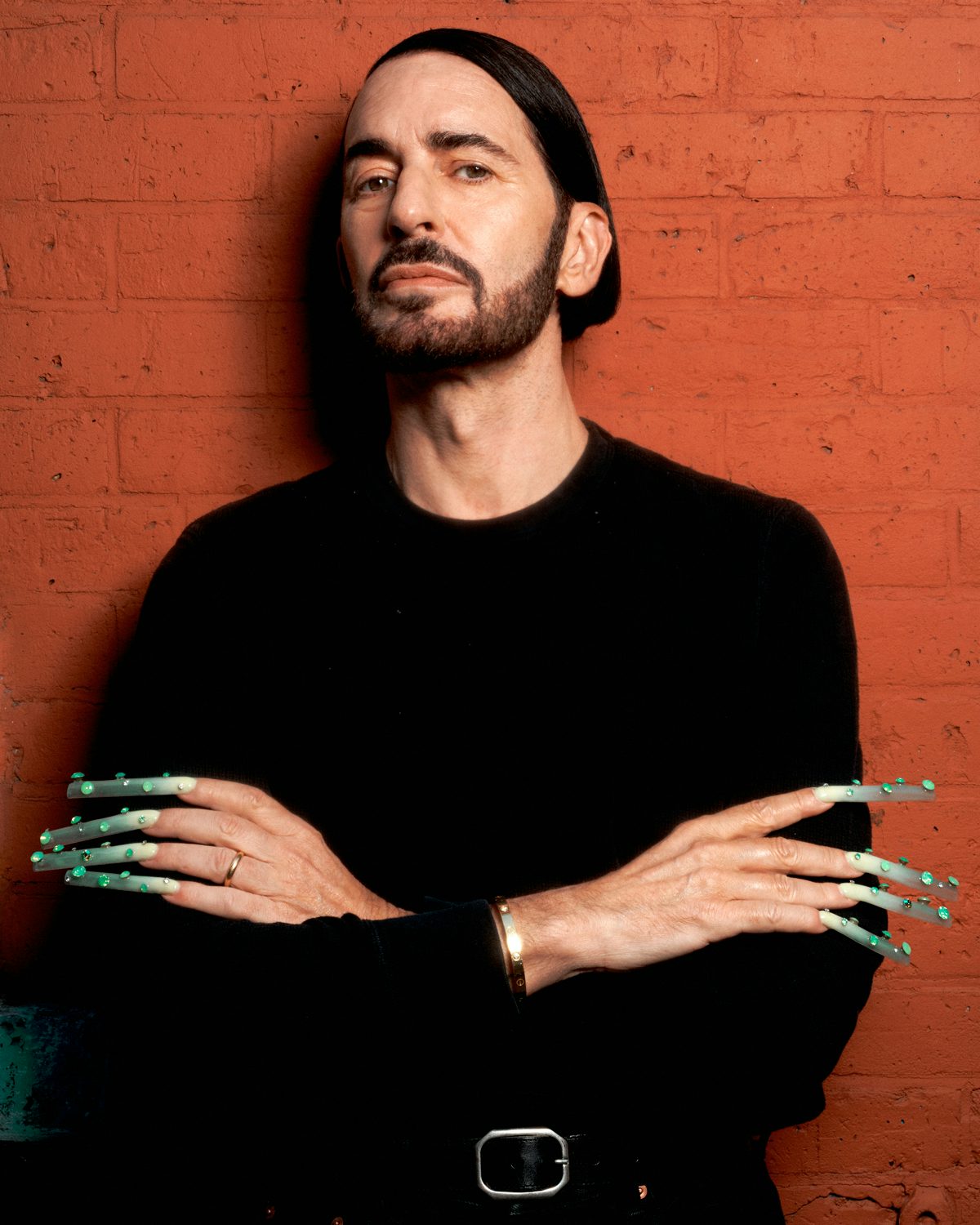

Recognising his value is something that photographer and art director Jackson Bowley has struggled with throughout his career. “I think when I first started, I was a bit delusional with how day rates worked and how to charge people. It’s a minefield!” he says. “How do you value something like taking a photograph? From an artistic perspective, or a time-spent perspective? Sometimes a £6,000 project fee at first seems incredible, but when you break it down, it’s not so great.”

Bowley, who is now signed to Sn37, acknowledges that having an agent can be hugely beneficial for artists as it allows for someone else to do any negotiating on their behalf. “But I don’t have a concrete day rate. In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever really been paid the same for a job ever, it changes every time,” he adds.

You’ve got to think about behaving like a business and building your business in the way that you would if you were bigger than just one person

For those without an agent, or who are only just starting out in the industry, Field’s key piece of advice is to start thinking about yourself as a business as well as an artist. “If you’re working with design studios and advertising agencies and editorial titles that are national or international, you are a business. So you’ve got to think about behaving like a business and building your business in the way that you would if you were bigger than just one person,” she says.

“Consider what you need to be paid as a salary, think about how much time off you require, and think about all the other things, like what you need to put aside for income tax, national insurance, all those practical things. Then from that, do the math and work out what your day rate should be. That’s the basis of how to charge your time out so you are covering at minimum your basic needs. As an illustrator, you mustn’t forget about the licensing and usage fees as well, as this is a large portion of where you’ll make your income.”

Whether you’re freelancing or full-time, the sad truth is that people from underrepresented groups, who often haven’t gone down the traditional art school route, are still far more likely to earn less than their peers. “One of the core barriers to entry is if you’re coming into the industry and you’ve not been to art school, or you are from a lower socio-economic background, you don’t already know people in the industry or have access to connections, that can be really isolating,” says Field.

The depressing stats around the gender pay gap and the lack of women in senior leadership roles in the design industry (17% versus 63% of graphic design students who are women) is what inspired How&How founder and ECD Cat How to set up GetEven, a pro-bono, studio-funded initiative designed to support women in the creative industries. So far, it’s organised virtual talks on subjects including knowing your worth, which featured financial coach Alina Burlacu and financial literacy creator Mykail James, aka the Boujie Budgeter.

I think that having more transparency is definitely less stressful overall for people and it just cuts a lot of the crap

Since founding the studio in 2020, How has also been tackling the industry’s money problem with a commitment to publishing its salary brackets and paying peers the same amount from the get-go. “I think that having more transparency is definitely less stressful overall for people and it just cuts a lot of the crap,” she says. “Obviously we want to encourage ambition as well, which is why we do give bonuses. But I think by just being open, maybe it means that we can actually have better conversations about it and it’s not so cloak and dagger.”

Her advice for creatives searching for fairly paid permanent roles is quite simply to “do the research”, whether that’s reaching out to friends in the industry, people who are doing similar roles via Linkedin, or recruitment companies, who often publish reports on average salaries.

Similarly, when it comes to hiring freelancers, How’s found that encouraging greater financial literacy is to everyone’s benefit. While there’s still a lingering sentiment among some in the industry that having a cheap day rate will automatically get you more work, in her experience it can often be the opposite. “You expect that person to have knowledge of their skill and how many years they’ve been doing it. So sometimes when the day rate is at odds with how long someone’s been working for, it shows they don’t quite understand their value,” she adds.

Field agrees, adding that continuing to devalue what commercial artists do is only going to drive more talent out of the industry altogether. “There’s so much rhetoric about how little illustrators earn, they probably don’t even think they could get a £10k job, let alone a £100k job. If that is the prevailing rhetoric, you end up buying into that starving artist trope and thinking that you’re doing it for the love of it and it’s not a proper viable career. Despite it being difficult right now, which we can’t ignore, it is possible.”

It’s so nuanced but I think you’ve just got to follow your gut, and if you have a feeling you’re being taken advantage of, listen to it

For illustrators and other commercial artists, her main piece of advice if something lands in your inbox that you don’t know how to price is to reach out to peers and, depending how big the job, agents like Jelly. “We will always try and help anybody that comes our way for a bit of advice, because I think you’ve got to be community minded. Depending on the scale of it and the level of help needed, it could be that somebody would offer to run it for you and negotiate it for a percentage, or it could be that they just give you a bit of advice. We do both. There are many different ways an agent can add value.”

With life getting more expensive in general, knowing your worth is more vital than ever for creatives. But there’s also the question of how to balance this with ‘value’ beyond the monetary – whether it’s a cause you feel passionately about, or a small business you’ve always wanted to work with. “I try to do projects that I don’t really make much or any money on because they excite me, or it’s something that I’ve always wanted to try out,” says Bowley. “It can be a privilege to be able to take those projects. They’re usually funded by doing pretty boring and laborious commercial jobs that pay well. But that’s part of the package I guess.”

While Field says she’ll never weigh up the merits of a project for their artists purely based on money, she does offer a word of warning about low or unpaid work. “You could soak up every single little bit of editorial work that comes your way, burn yourself out because you’re working so hard on really tight deadlines, and be earning less than a viable living wage. And if you haven’t done the math, you’re going to be like, ‘illustration is not sustainable for me, there’s no money in it’. It’s so nuanced but I think you’ve just got to follow your gut, and if you have a feeling you’re being taken advantage of, listen to it. You’ve got to think, does it serve you and your long-term strategy?”