Exposure: Hero Bean Stevenson

Shot mostly in black and white, and containing a quiet and thoughtful intensity, the work of Hero Bean Stevenson offers up soulful portraits and a new style of fashion photography

Outside of an academic framework, we rarely discuss artistic lineage in photography – how artists and their approaches are in dialogue through space and time. Yet these intergenerational connections, whether conscious or subconscious, unravel a myriad of ideas about photography, how we see, and how pictures shape our relationship to contemporary life.

I discovered the work of New York-based photographer Hero Bean Stevenson on Instagram and was instantly captivated by her quiet portraits of people and animals set against understated backgrounds. They conjured an obsession with feeling, carefully brought to life through movement and gesture. What’s more, her tender monochromatic pictures felt like a conversation with renowned artist Peter Hujar, a key figure in the cultural scene in downtown Manhattan in the 1970s and 80s admired both for his exquisite work and an uncompromising attitude towards work and life.

Like Hujar, Stevenson crafts highly emotional photographs stripped of any excess or superfluous detail. They both share a quiet refusal to pander to the marketplace, understanding the circumstances in which they do their best work, and a desire to protect their creative autonomy. Also, both photographers share a fascination with beauty and pleasure — an inquiry often deemed frivolous by academia, despite it being fundamental to the human experience.

Stevenson, who is 28, was introduced to photography at a young age by her mother, who would actively make work throughout her childhood. “I always paid close attention to when she would pick up her camera,” Stevenson tells me about this early encounter with the medium. “There are often times when my brother or I would burst into tears over something, and instead of immediately tending to us, her impulse would be to pick up a camera. Watching her taught me that certain moments deserve to be preserved.”

She initially studied art history and psychology, propelling her desire to build deep relationships with her subjects and explore their inner lives. “I’m a really slow photographer,” explains Stevenson. “I’m not somebody that’s snapping away. It’s a lot of looking through the viewfinder and waiting until something strikes me as necessary.” Interestingly, Hujar’s process was similar. He didn’t direct his subjects, but instead waited without asking for anything or saying too much.

It’s not just people who captivate Stevenson; horses are a recurring motif in her commercial and personal work, capturing an aura of majestic possibility and monumental physicality without being fetishistic. “Horses have been the most important presence in my life since I was a child,” she tells me. “They are so deeply therapeutic — connecting us to who we are on a primal level — there’s a soul connection that happens with these animals that’s really indescribable. In many ways, horses have totally informed who I am as a human.”

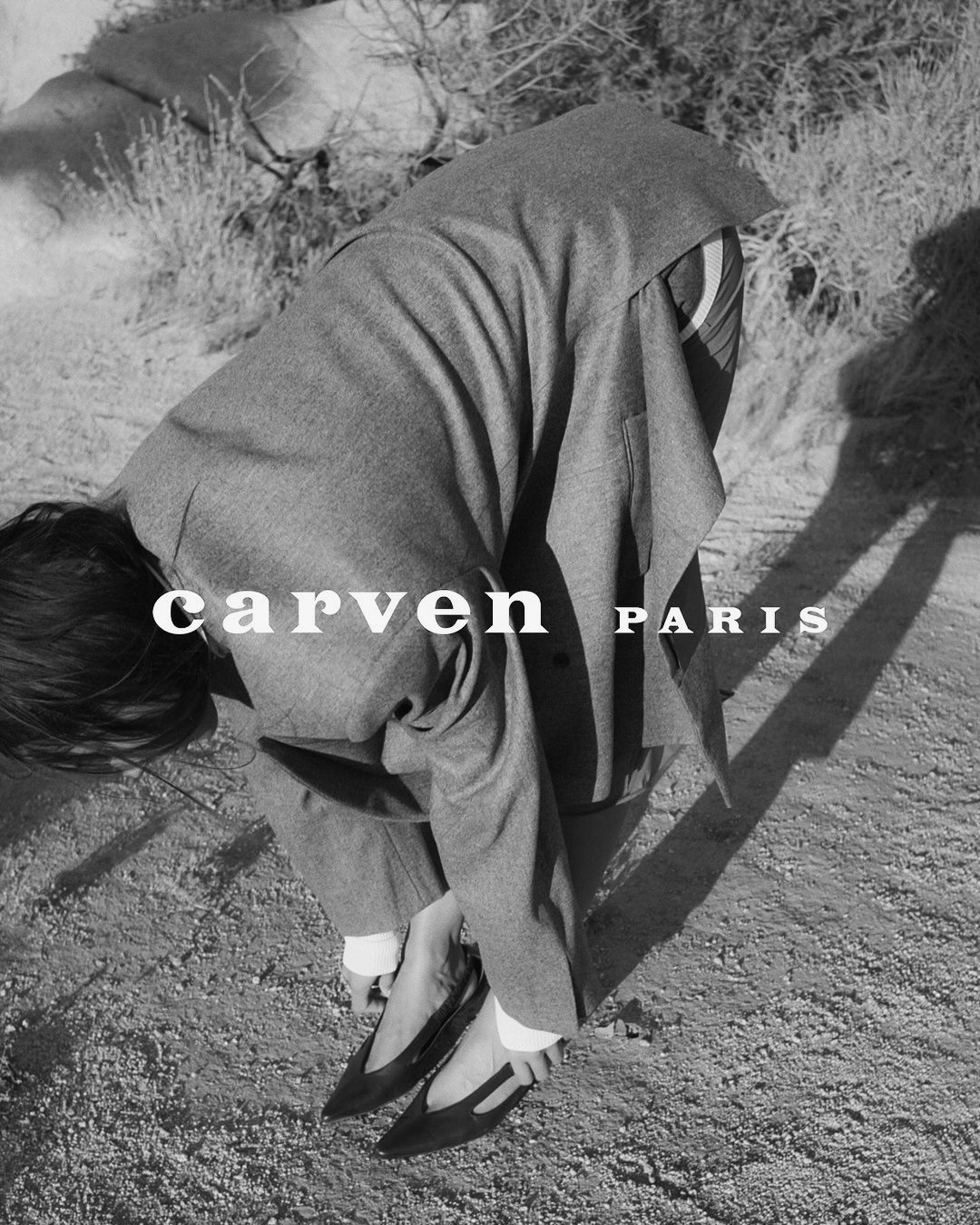

In her first campaign with the French fashion brand Carven, Stevenson brought a strong equine presence. Shot in a small ranch in Joshua Tree, surrounded by a rocky sun-bleached landscape, the photographer collaborated with friend and dancer Marcela Kuara and a horse named Yella on a dreamy series that breaks away from the cold satire that’s dominated fashion for the last two years. Tender and textured, the campaign embodies the photographer’s ethos, blending a slow, intentional process with stories deeply connected to the natural world.

“This project gave me hope that the version of fashion photography I’ve always dreamed of still exists,” explains Stevenson, who kept the team small, with no stylists or assistants. “Carven gave the work time and respect. I was given full creative control without thousands of digital deliverables and I was able to shoot the entire project on film!”

Instead of constructing a project idea, Stevenson builds work image-by-image, letting the wider concept emerge over time. Take her series on older artists, including portraits with director Tony Kaye and Werner Herzog, ceramicist Magdalena Suarez Frimkess and sculptor Marie Lalanne, to name just a few.

“I’m really drawn to taking pictures of people who have lived life,” she says passionately about the ongoing project. “People that are fearlessly pursuing their artistic calling. I take a lot of comfort in their lived experience. I think this work is born from an anxiety around our experience in the world being so limited. Ever since I was a child, I’ve had this understanding of my own mortality.”

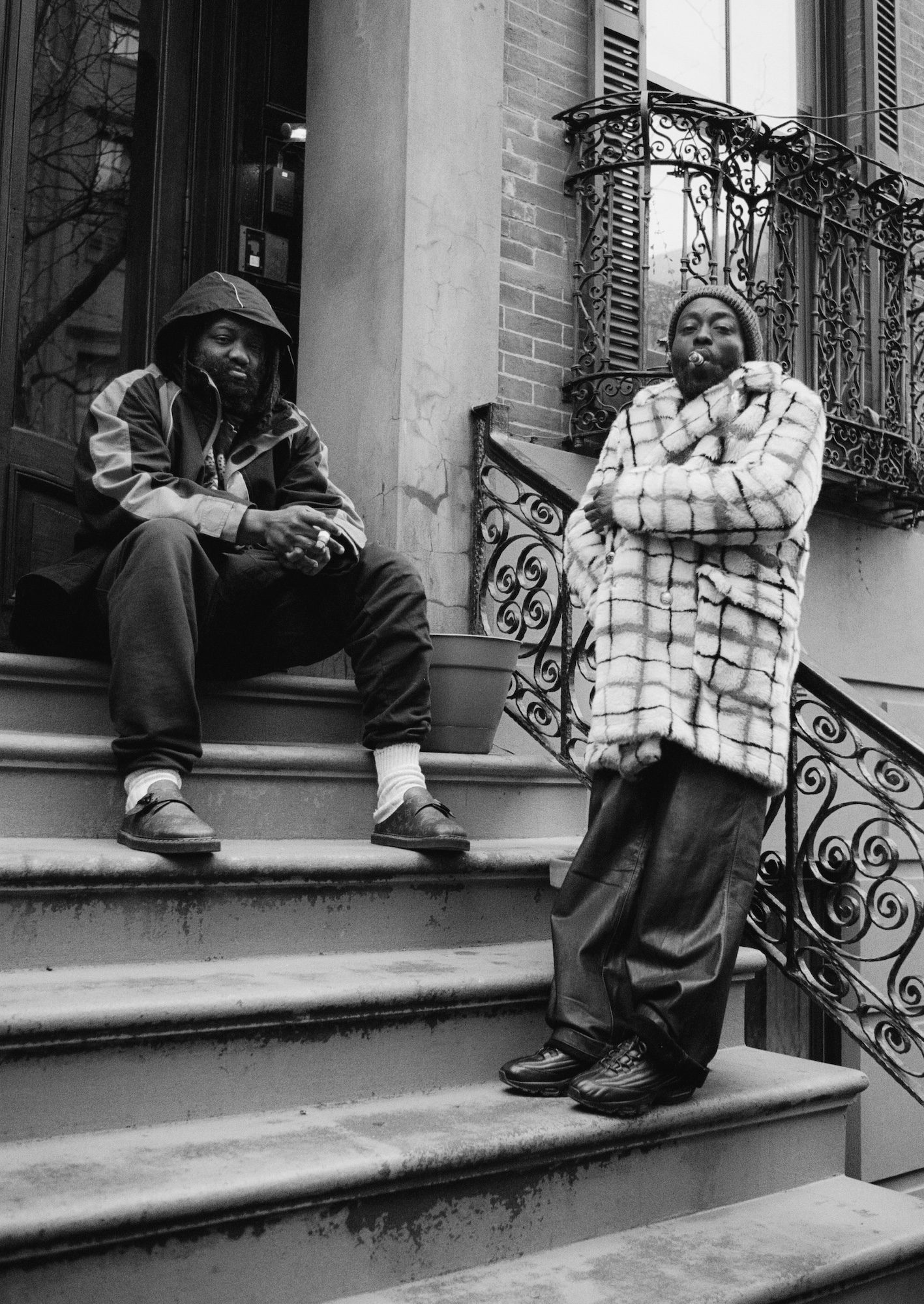

Stevenson has recently expanded her practice into filmmaking, writing and directing her first short, Heaven Is Here, in collaboration with performer Joshuah Melnick and cinematographer Shane Sigler. Shot in several locations on Long Island, the film unravels themes around time, memory, masculinity and the body in a subtle yet transfixing narrative that leaves you craving more. It’s hard to deny the feeling that Heaven Is Here marks a new era in Stevenson’s journey, one that might render photography a stepping stone rather than her final destination.