Gregor Petrikovič on what it means to be human

Artist Gregor Petrikovič, who is part of our New Talent 2024 showcase, explains how he is using artificial intelligence to explore the human element that differentiates us from the machine

Some people collect rare prints or limited-edition trainers; Gregor Petrikovič has a “silly archive of human interactions”. The Slovak-British filmmaker and artist began his ‘conversation collection’ on an old iPhone eight years ago during smoking breaks between lectures while studying philosophy at Durham University. “My friends were saying cool things I knew I wouldn’t remember. I asked if they’d mind if I recorded.”

Petrikovič started to record conversations in pubs and club toilets, with no real intention. His education took him to London, where he was awarded the Burberry Design Scholarship at the Royal College of Art and enrolled in the graduate photography programme. However, it wasn’t until he moved to New York for a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program that he realised there was something in his growing archive of chats.

He had just started running the audio through software that spat out “transcripts of real life” when he had a studio visit with a curator from the Czech Republic. “He saw them in the corner, shoved against the wall, and asked what they were. I told him they were scripts of life that I was recording,” Petrikovič recalls. “He’s like, I think there’s something there.”

Spurred on, Petrikovič started to analyse the scripts, finding they were very fictionalised. “I mixed the real-life recordings with AI-generated visuals for a demo film called Sincerely, Victor Pike, which sits between the documentary-fiction boundary,” he recalls. “The film explores the capacity of technology and AI-generated visuals to preserve the ephemeral nature of human interactions.”

Despite using AI to create Sincerely, Victor Pike, he describes it as a film with a human heart, because “it speaks about humanity”. The filmmaker is fascinated by what it means to be human. “We’re living in a post-human era. We’re dependent on technology,” he reflects. “My focal point is, what is the human element that differentiates us? What is at the core of humanity? Then I merge it with technology and AI.”

We’re living in a post-human era, dependent on technology. What is the human element that differentiates us?

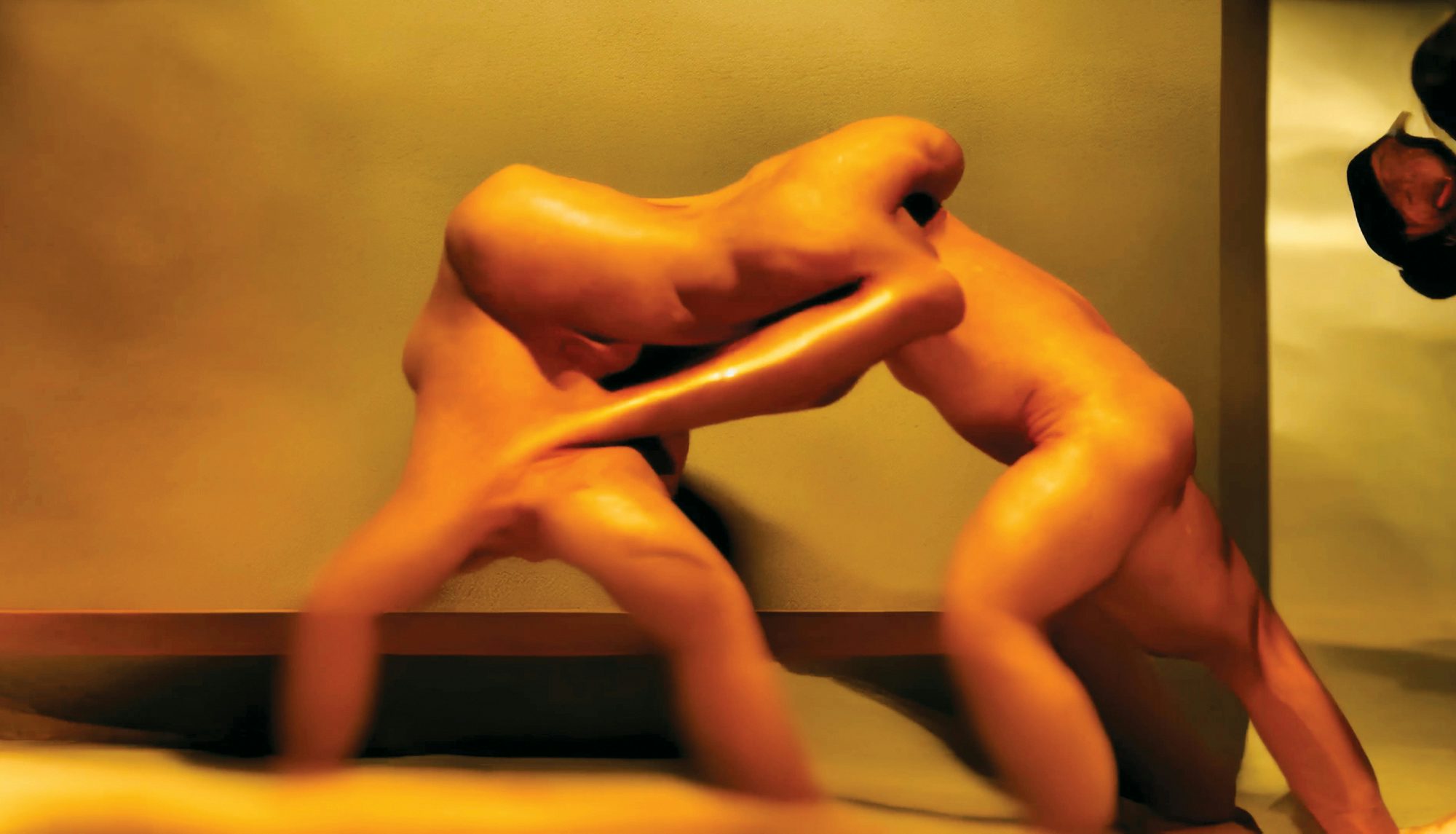

Petrikovič has since fed wrestling footage into generative AI software to explore nuances of queer intimacy with Me vs You, a multi-channel video installation in partnership with artist Adam Cole. He’s also morphed AI-generated video with 16mm film footage to create a dystopian darkwave music video for Douglas Dare, and an experimental music video where renaissance meets tech surrealism for Drum & Lace. He is now working on an AI pilgrimage where the machine tells you what to do, where to go. “Sincerely, Victor Pike is about AI interpreting human actions. I want to move towards AI giving commands,” he says.

Despite his experiments, Petrikovič says he’s not technology-obsessed in everyday life and is happiest when furthest away from society. As a child growing up in Slovakia, Petrikovič loved to dance, and because his mother was a costume designer and seamstress, he grew up among fabrics and clothing.

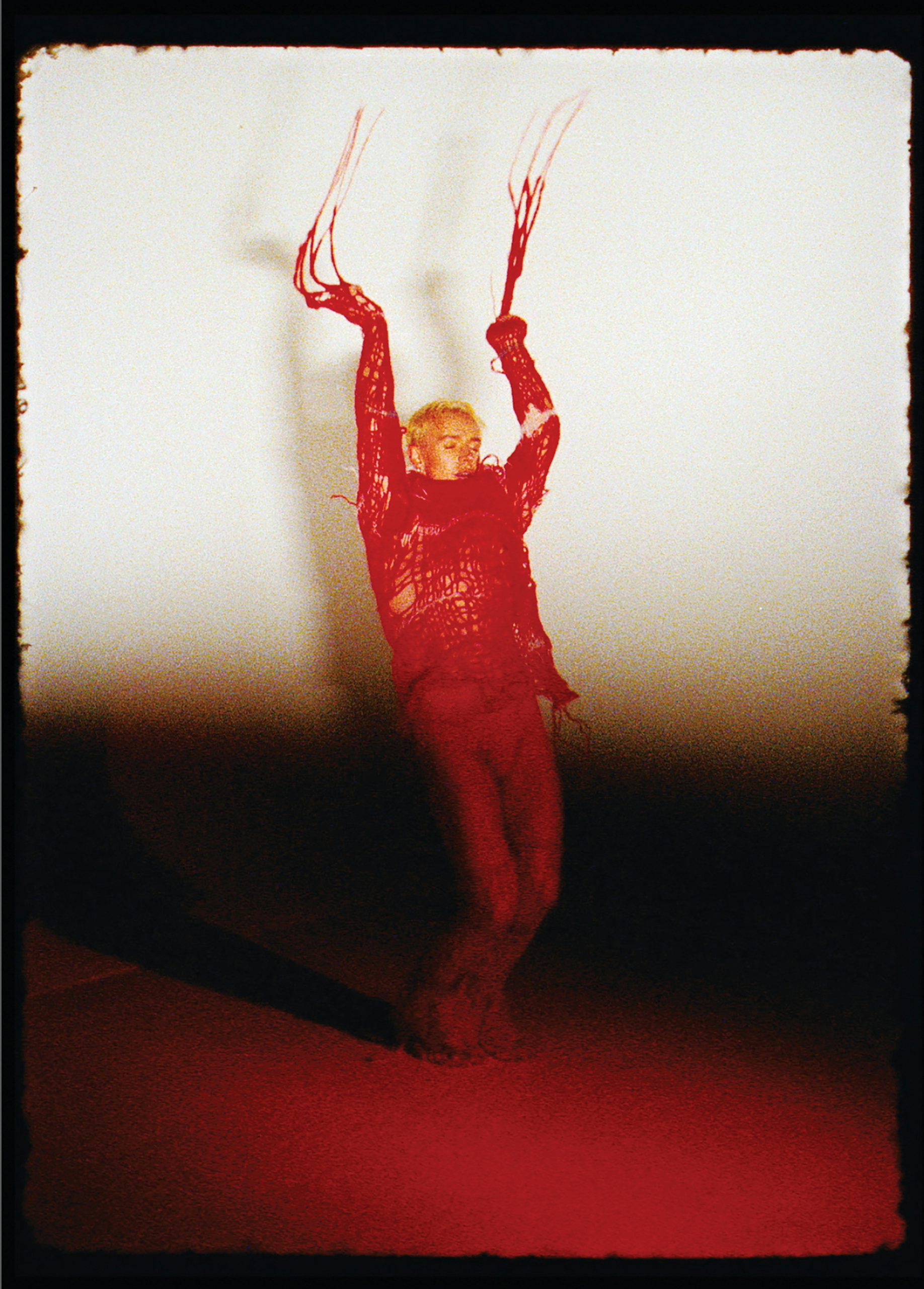

Naturally, his early work centred around movement, and he gravitated towards bodies or anything figurative. Notable work from this period includes One, Another, a movement-driven visual poem based on the ancient Greek myth of soulmates, which Petrikovič filmed against New York City’s urban landscape; and Figura Serpentinata, which features four female dancers who adopt sculptural poses based on late-Mannerist sculpture.

“For a long time, I found it more natural to engage with dancers than with actors because it wasn’t centred around the spoken word or the idea of a character. It just had the immediacy, the flow. It’s not an A to B action; it’s very fluid. It’s not a means to an end for its own sake; it’s pure expression.” Petrikovič is unsure whether movement is as present as it used to be in his current AI work.

“Strangely, the art stuff is going better than the commercial stuff,” Petrikovič says, finding that one art project leads to another. Sincerely, Victor Pike won the Solo AI Award at Colección Solo in Madrid. As a result, the film was exhibited at the gallery, the +Rain Film Festival at Pompeu Fabra University and Sónar+D 2024, both in Barcelona.

“Colección Solo mostly pushes for digital art, electronic work and time-based media. The global competition had good PR around it, so it took off from there … a chain thing,” he muses. He was selected for next year’s Flamin Fellowship by Film London and Arts Council England, which supports early career artist filmmakers. “The third fun thing was I got into the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, which wants to adapt Sincerely, Victor Pike for a planetarian dome,” he shares.

Despite his good luck in the art space, Petrikovič wants to merge his personal and commercial work. “I want to go into commercial because I want to move on to slow cinema feature film,” he says. “I always loved film and knew I wanted to be a filmmaker, but I subliminally ignored the fact that, since I was a kid, I can’t watch a whole film in one sitting … until I discovered slower cinema, which I could comprehend.”

A late ADHD diagnosis met by undiagnosed sleep apnoea led Petrikovič to understand his need to record conversations. “My brain never got into the REM stage to save memories before I started sleeping with a machine and tube,” he says. “Interestingly, the pace of recordings has decreased since I did.” Despite his battles with comprehension deficit, Petrikovič has a positive outlook. “I can see how people think ADHD is a strength. It helps me make creative associations.”

As minimalist slow cinema, with its long takes and deliberate pace for distracted brains, calls out to him, he laughs: “The goal is to make what I want to make, and it will find the space where it belongs … right?”