Vanessa Saba and the evolution of collage

Collage is an alchemical and subversive process, perfectly suited to our fragmented times. And as artists like Vanessa Saba are showing, online it has reinvented itself yet again

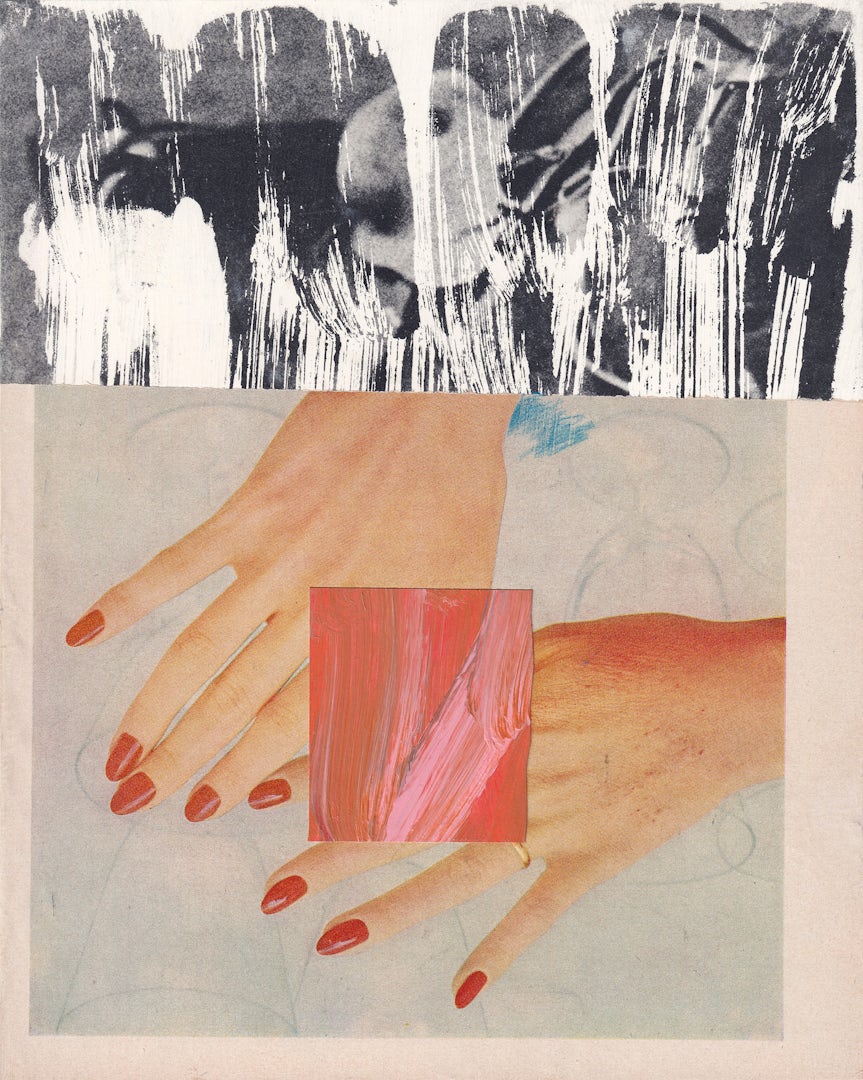

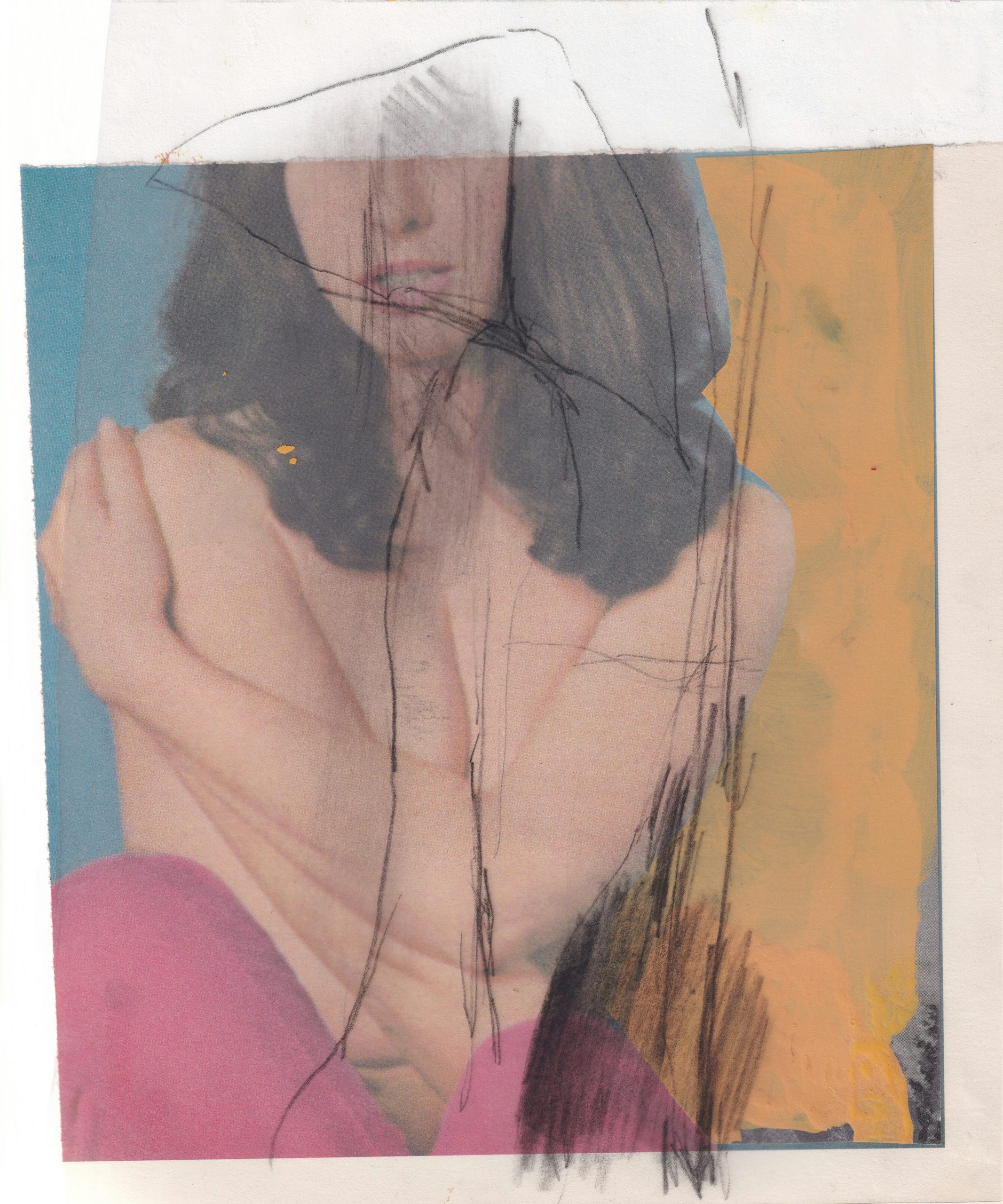

From her studio in Brooklyn, New York, Vanessa Saba makes striking collages, many of which have appeared in US publications in print and online. Her work largely revolves around imagery obtained both from print sources and photo libraries, sometimes with the addition of pencil, paint or fabric. The results are powerful and eye-catching – and recently they have also started to move.

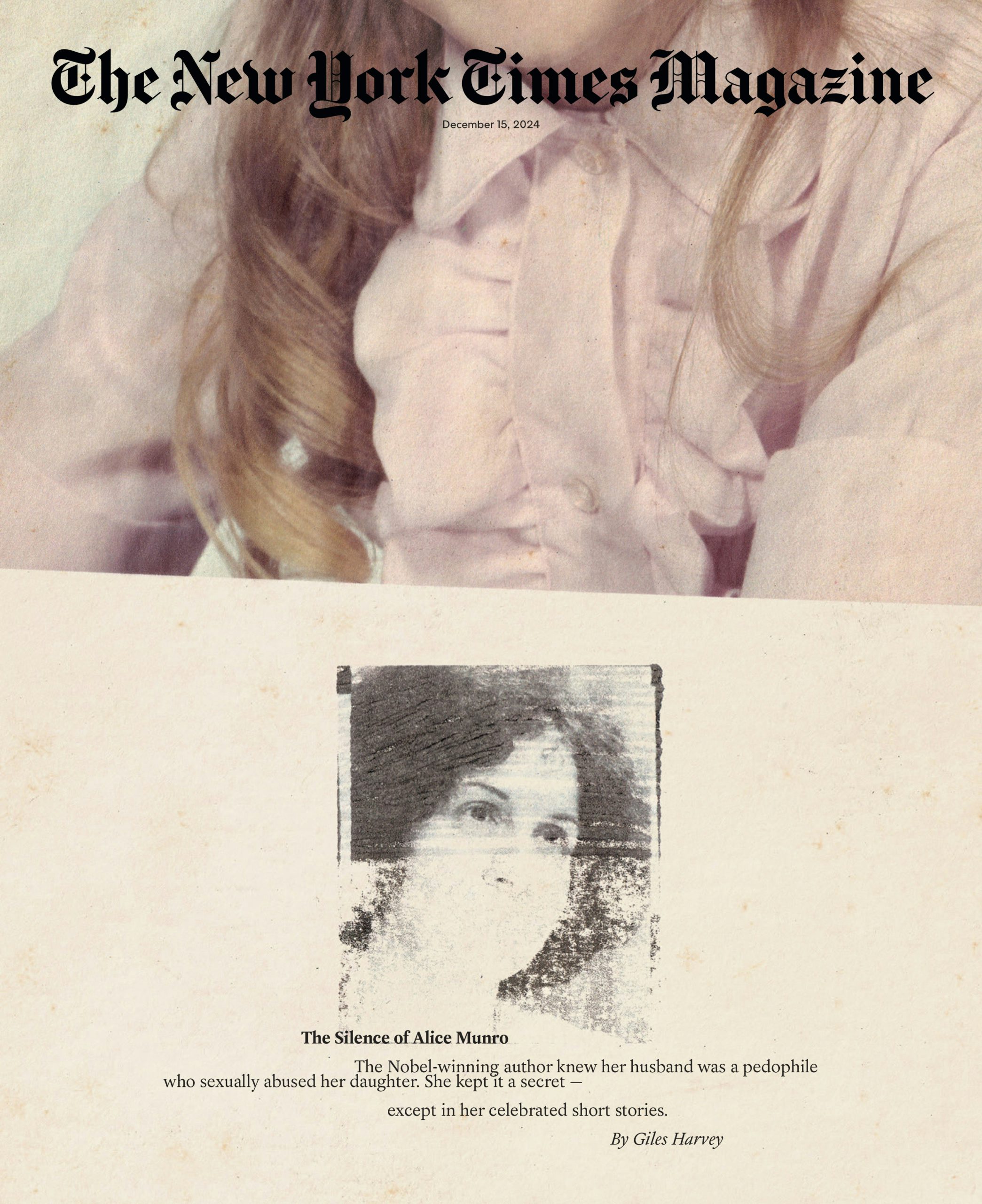

Saba’s commissions are most often seen in an editorial context, in places such as the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker and the Atlantic. And while collage can distil a story into a single image, it occupies a different space to illustration, she says – its material difference being that it’s constructed from pre-existing imagery, but the process, she explains, is also more about conveying a sense of something from a given text.

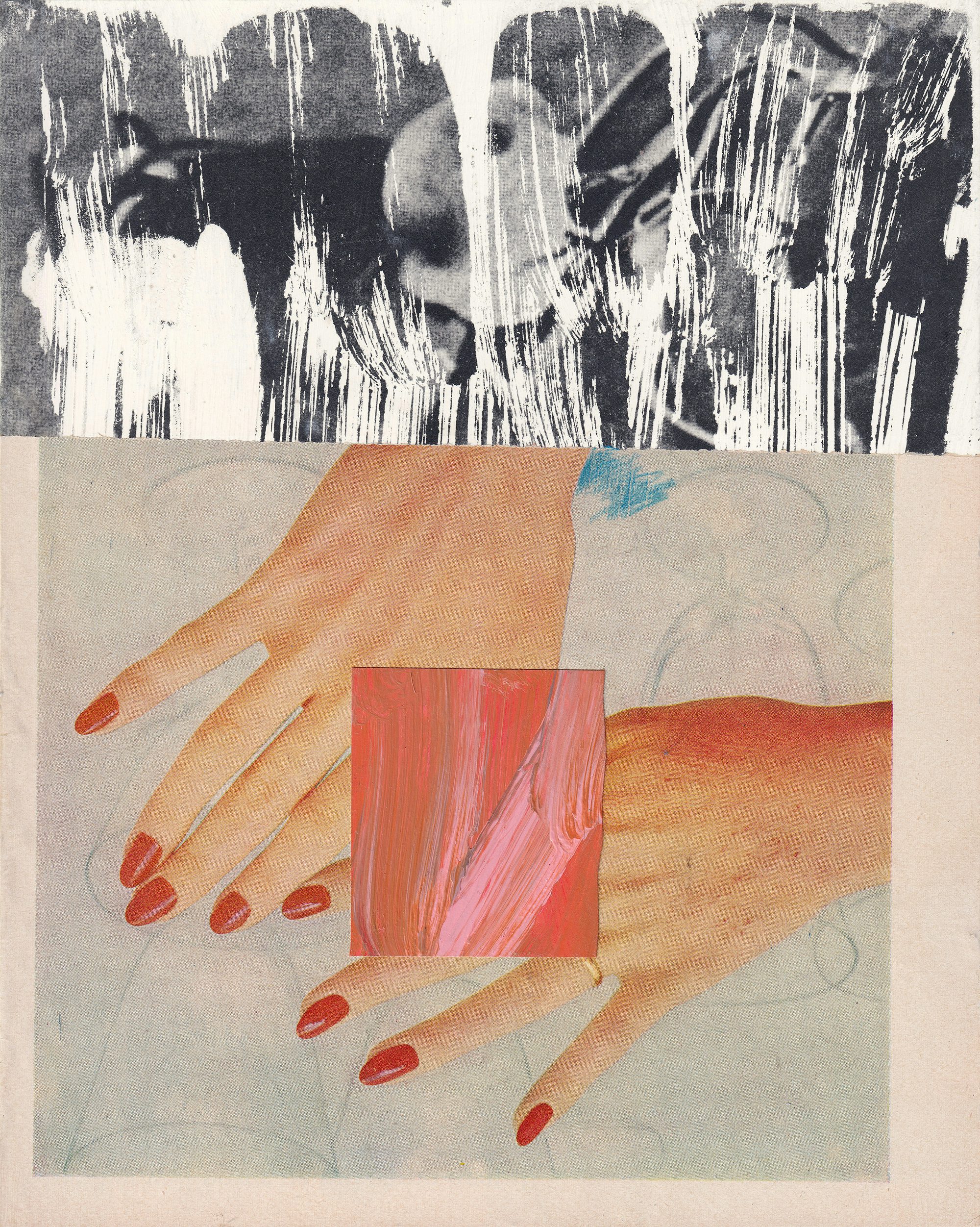

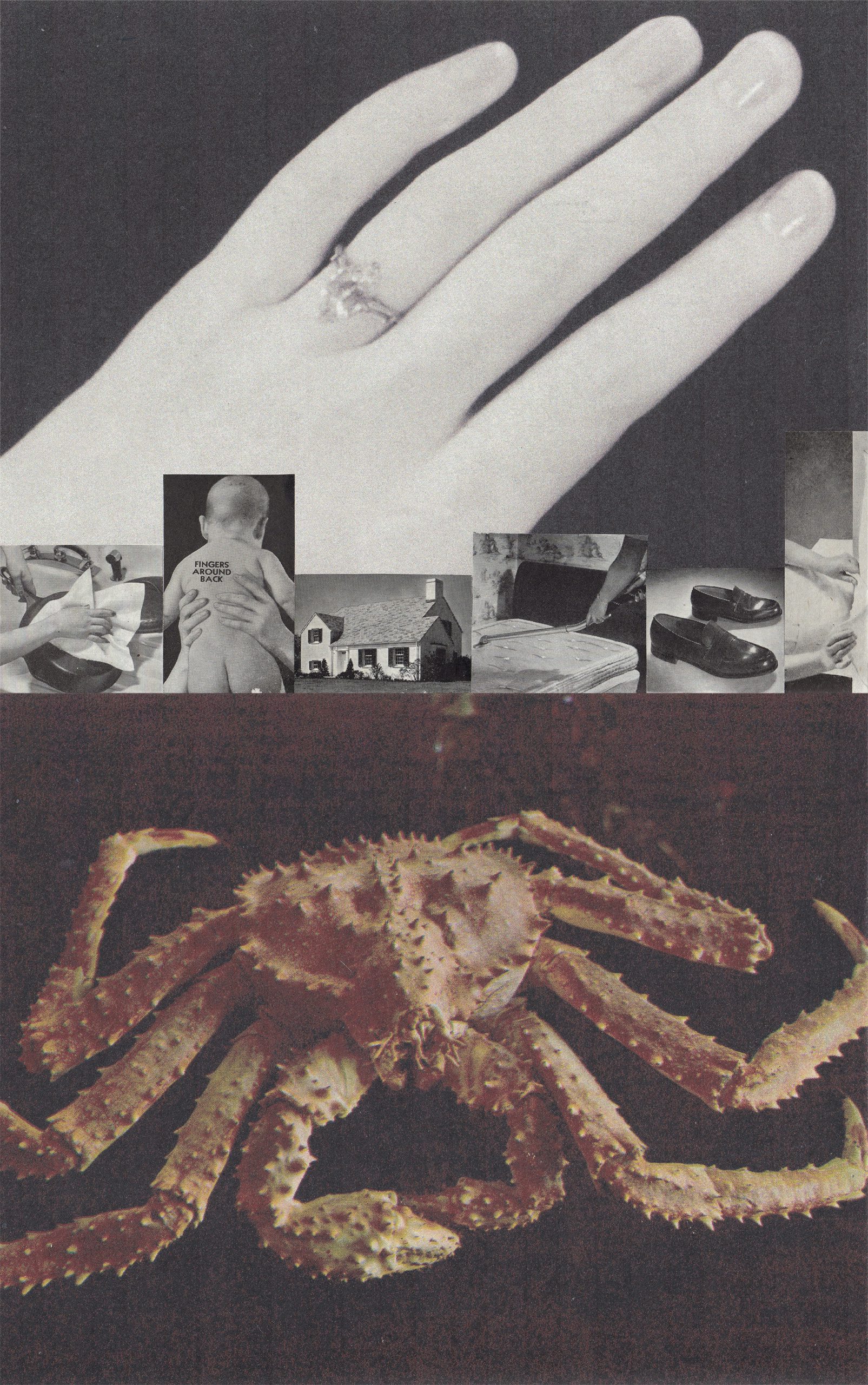

Despite its inclusion of disparate sources, collage is often a minimalist medium, with Saba’s creative decision-making based on “how [I] can communicate something powerfully, without stripping it of its depth or complexity, [while] making only the necessary visual moves. I’m really not aiming to illustrate a written piece or illustrate a narrative,” she says. “I’m looking to get to the essence of the feeling of it and to then conjure that in the artwork. This typically results in work that is somewhere between being figurative and abstract.”

Collage has been a part of Saba’s life since early childhood, where she created assemblages using card, paper and paperclips at bedtimes, and spent a lot of time in her father’s art studio. She went on to study graphic design at the Rhode Island School of Design, not really knowing what it would entail.

“Collage was the foundation of my creative practice and, in many ways, it led me to graphic design in the sense that I was fascinated with pulling together and layering these different visual elements to tell a larger narrative,” she says. Having veered away from the subject, Saba was even unsure of working in the industry after graduating in 2009, but ended up putting her degree to use.

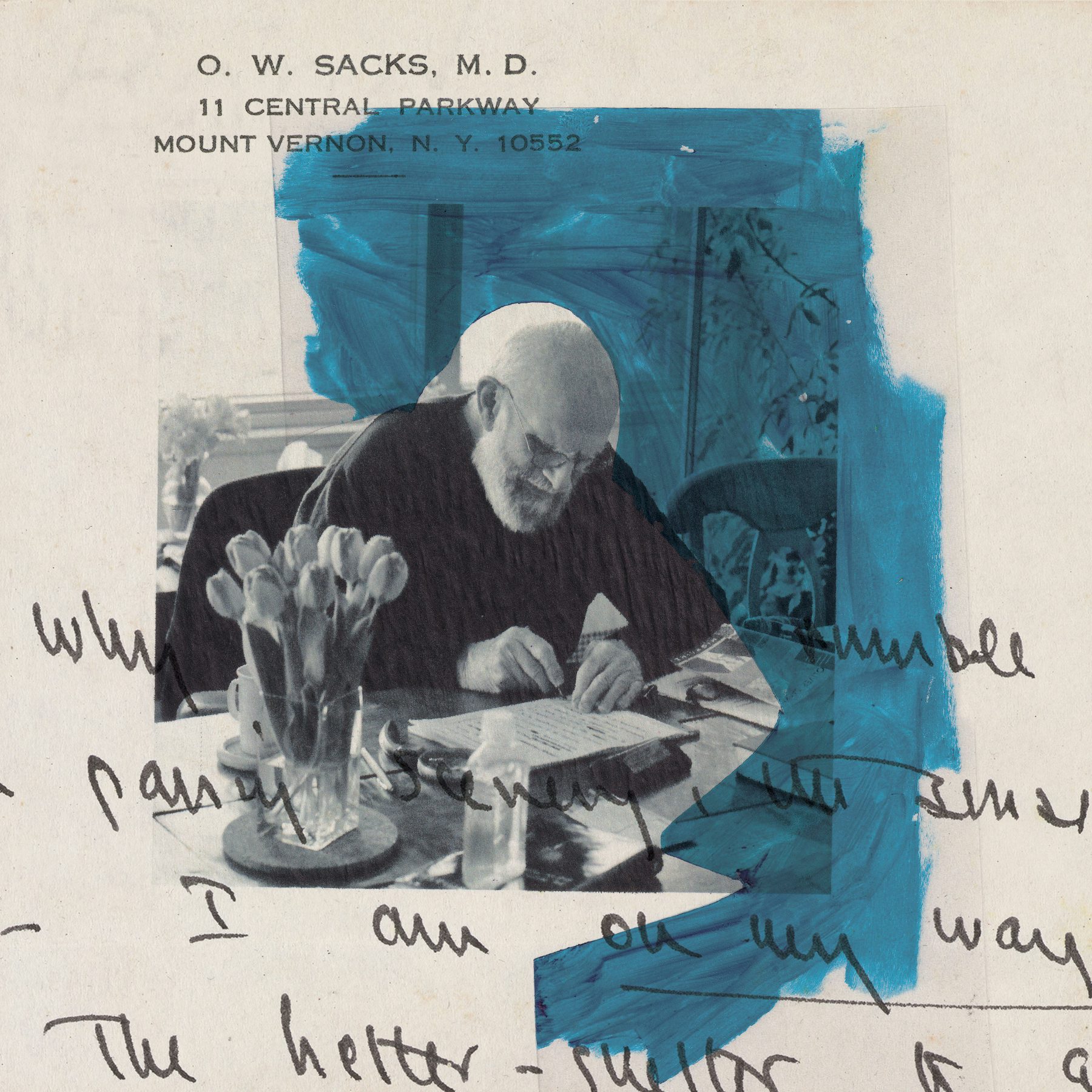

“It was about ten years before finding my way back to my collage practice in earnest,” she recalls. Her first commission, from creative director Lindsay Ballant at the Baffler, required sourcing imagery relating to Second World War veterans (and involved an eBay purchase and a trip to buy direct from a collector).

While she continued to work as a graphic designer (she is also the creative director of the brilliant Mother Tongue magazine), Saba carried on making collage work – and it was a few years until she received her next commission, from Frank Augugliaro, then design director of the New York Times’ Opinion section.

“At that time I was creating collaged postcards that I was exchanging with my father,” she says. “Using vintage postcards, I would create a minimal visual intervention before popping them in the mail to my dad. Frank saw the ongoing series on Instagram and I’m grateful that he could envision the potential for my work to fit within an editorial context. When he reached out regarding the commission, I was absolutely ecstatic about the opportunity but also quite intimidated.”

You take one thing, you put it next to something else, and it is changed – it has new meaning, it invites new interpretations

The visibility that the NYT work provided led Saba to other commissions and she began to single out the kinds of writing that her work could best respond to. “Usually the weightier, more sensitive and human-centred pieces,” she says. “I find my work is best when it’s responding to a strong emotional current in the written piece.”

For Saba, collage is appealing as a medium for several reasons. It has an immediacy (no wrestling with the technicalities of a material or process, she says) and is egalitarian in nature, given that found images are accessible and cheap, with no need for expensive art materials. That isn’t to say the work comes together without a process or even a struggle. “Of course, there’s the working and reworking, the grinding, the doubt and all of the turmoil – and exaltation! – that can go into any artistic practice. But there’s no learning curve for the most part,” she says.

“Collage also embodies a fascination I have always had in this sort of alchemical process that happens with shifting contexts, with putting things in relationship to one another,” she continues. “I notice this fascination first in myself – the way I can feel my own internal chemistry or energy shift depending on who I am talking to, who is in the room, the room itself.

“These shifts, these potentials for connection or disconnection, ways of relating to one another, ourselves, our environments is something I have a heightened sensitivity to. As we overlap with the world around us, we are changed, and we are constantly deriving meaning from re-contextualising ourselves.”

This, in essence, is the mode of collage, she explains: “You take one thing, you put it next to something else, and it is changed – it has new meaning, it invites new interpretations.”

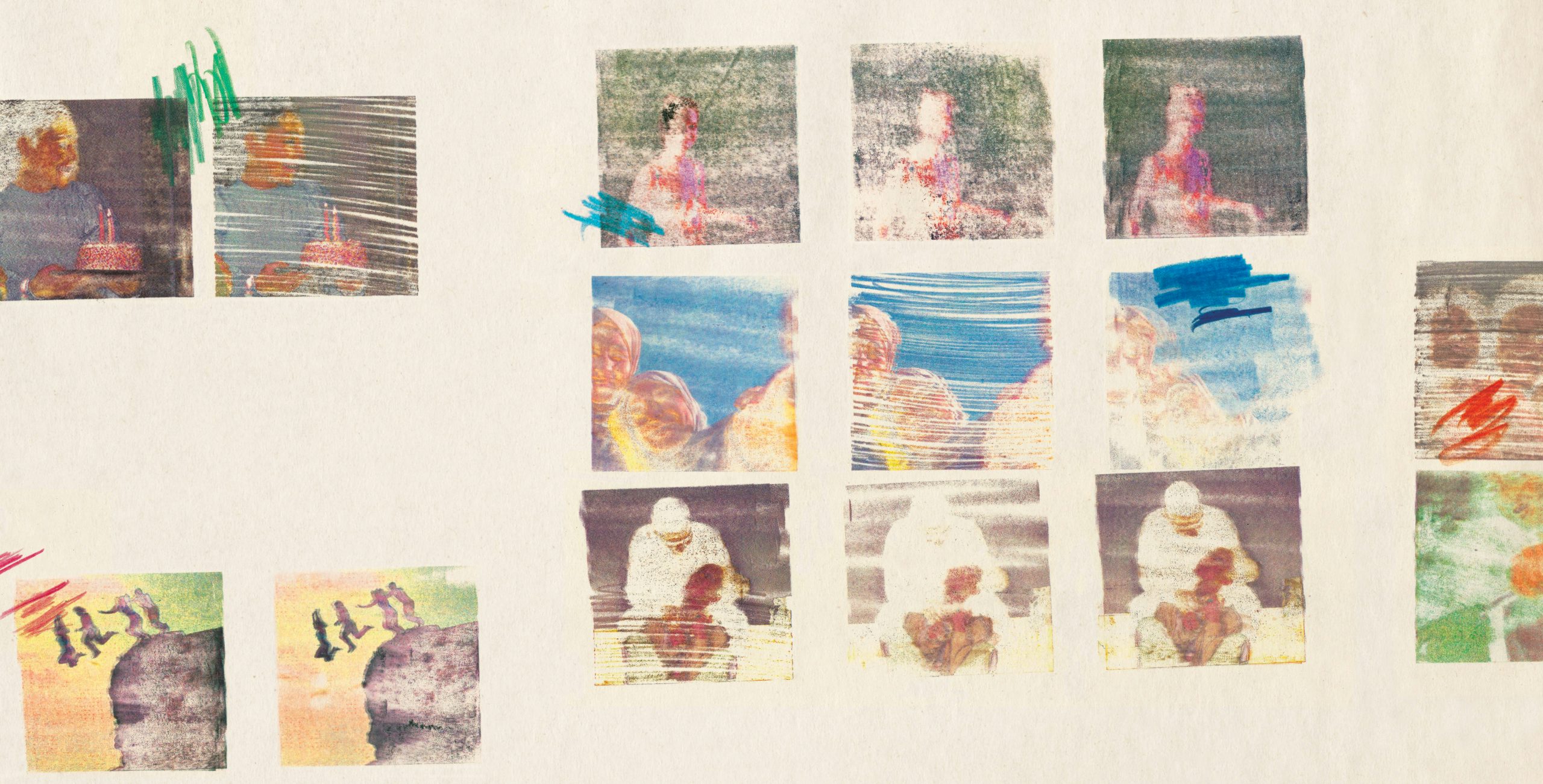

While contemporary collage has its roots in the printed creations of the early 20th century, the evolution of the medium today in the digital world has seen it make use of moving image, something that Saba explored in a recent commission for an essay in the New York Times.

Having been asked by art director Elana Schlenker to produce a visual for an article about the music of Leonard Bernstein being played at the Kennedy Center in the age of Trump, Schlenker suggested incorporating motion into the work. Saba paired a short, looping clip of Bernstein conducting with a clip of clouds drifting in the sky (shown above).

“While I think this could have been successful with still images, the movement drastically heightens the poetry of the visuals,” she says of the work. “In this instance, it pulls us into this melodic tempo of his baton and the movement of the clouds. It’s as if he’s conducting the sky, they’re both synced in their motion.”

The ability to animate a collage means the results can deal with larger narratives depending on what the content is paired with, alongside the use of pace and repetition, even audio. “Working with moving images allows me to bring in a temporal quality to the work and to then manipulate this based on the narrative,” Saba adds.

“In these examples, a movement repeated can either feel oppressive and excruciating, as it did in the personal piece I was working on [shown below], or transcendent and poetic, as it did in the Bernstein piece.”

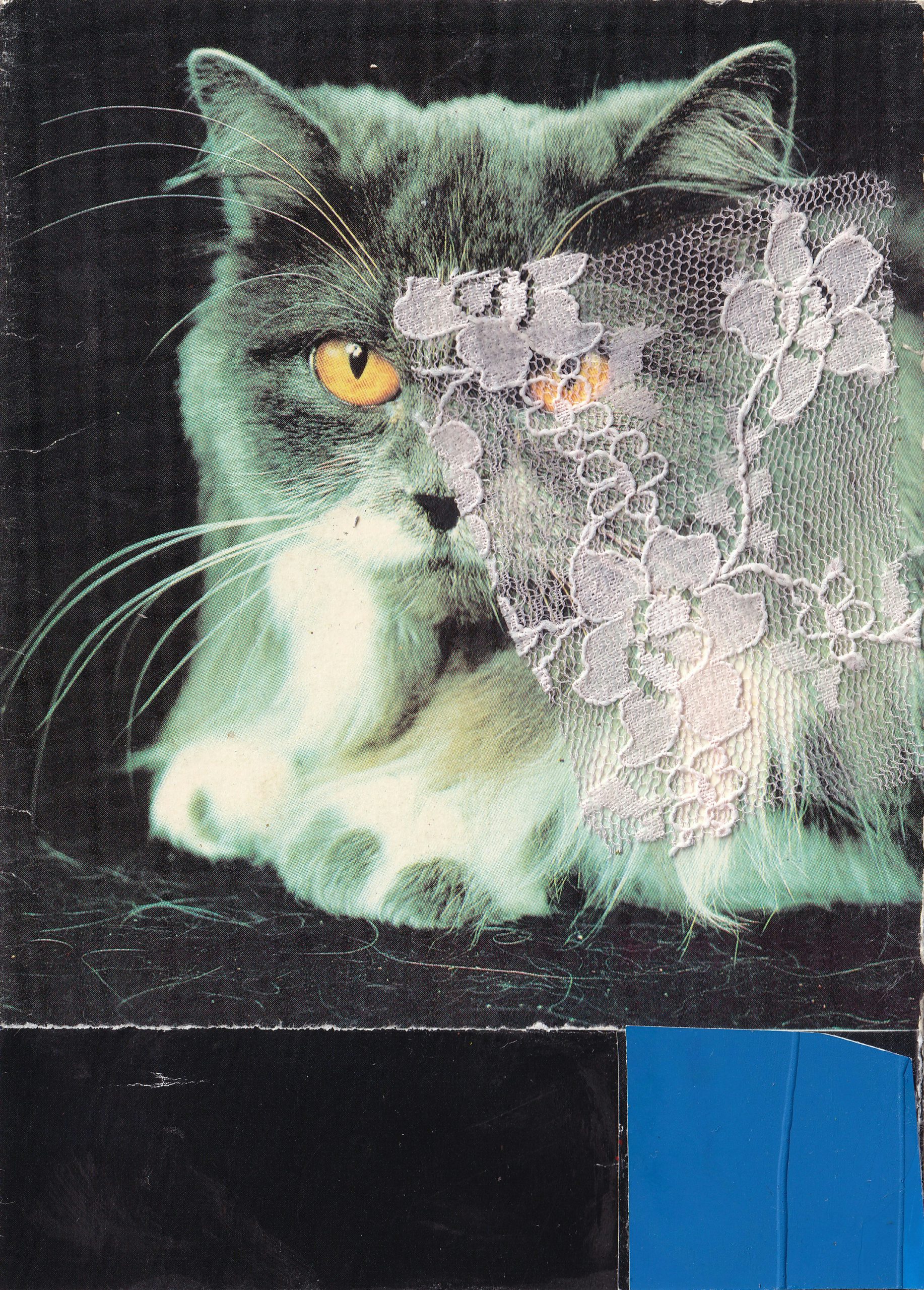

And while Saba enjoys the collaborative nature of editorial commissions, of working with art directors and editors, and seeing the rewards of contributing to a story, personal work remains vital. It sustains her professional practice and can be exploratory and experimental, a testing ground for new ideas in and of themselves.

“Tangibly and technically speaking, my personal practice is a space where I explore new techniques, materials, compositions, ways of bringing the work together,” she says. “I then take that into my commissions. It’s easy to become formulaic when working on editorial commissions – the turnaround times are fast, to make a living requires taking on an immense number of assignments.”

Saba is currently working on a series of photo-based diptychs (on “the echoes of my matrilineal line”), where the image selection, what is revealed or concealed, and how the images sit next to one another are all artistic considerations.

We happen to live in a time when we are particularly inundated with visuals, with media – it’s exceptionally saturated, overwhelming and honestly quite oppressive

She adds that her personal work is about responding to something “constantly pulling at me” and that, for years, “a sort of restlessness and melancholy was really just the lack of a personal artistic practice. There is something about life that makes sense to me when I’m working on personal work, it feels like an answer to an otherwise constantly nagging and questioning energy. It’s become quite necessary actually.”

Is there something in the idea that collage resonates with life today? Are we witnessing fragmented responses to increasingly fragmented experiences? “I do think collage has a particular resonance with the times on a number of levels,” says Saba.

“The most obvious is that we happen to live in a time when we are particularly inundated with visuals, with media – it’s exceptionally saturated, overwhelming and honestly quite oppressive.

“Collage [also] holds a unique potential for responding to its times, at any point in history, by working with the visual materials of its moment. In doing so, it’s a way of taking ownership of that material, to turn it back on itself, rather than simply being subjected to it.”

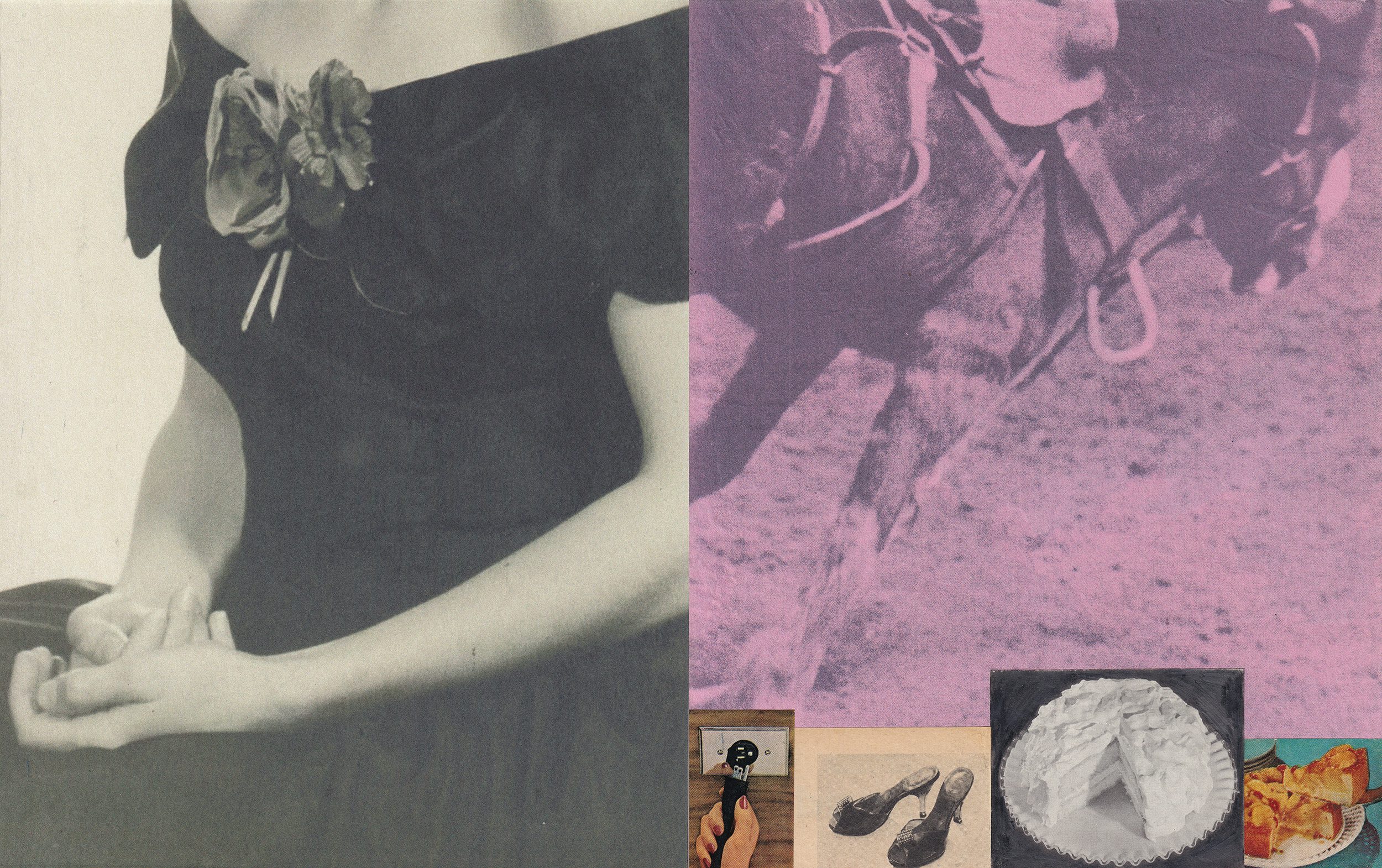

For example, Saba cites the kinds of visuals that would have been pushed towards her mother or grandmother – baby guides, home magazines, advertisements for beauty products or domestic products – the messaging of which remains remarkably similar to the ones we see today (“systems we haven’t yet been able to fully dismantle”).

“These visuals tell us what we should be putting our attention towards, what we should look like, what we should buy, what role we should play, how we can contort ourselves to conform, what information we should consider most relevant,” says Saba.

“There is a subversive role in taking those materials, which are not intended to be part of an aesthetic artistic space, and manipulating them to tell a different story.”