The Monthly Interview: Kim Hastreiter

We speak to Paper’s co-founder about launching the magazine during a pivotal point in New York’s cultural history, making the iconic Kim Kardashian cover that broke the internet, and why her latest project is a book all about ‘stuff’

Kim Hastreiter has always been interested in collecting things that tell a great story. “I’m a really good thrift shopper, or give me a thousand photographs and I’ll find the best one in five minutes. I guess it’s being an editor, but not even. I’m a good truffle hunter,” she tells CR.

As she chats away animatedly from her apartment in New York, nestled above Washington Square Park in Lower Manhattan, the gloomy winter’s day is immediately brightened by her trademark look of fluorescent glasses, Mao jacket and pleated skirt (her wardrobe is full of these custom-made uniforms in an array of materials for different occasions).

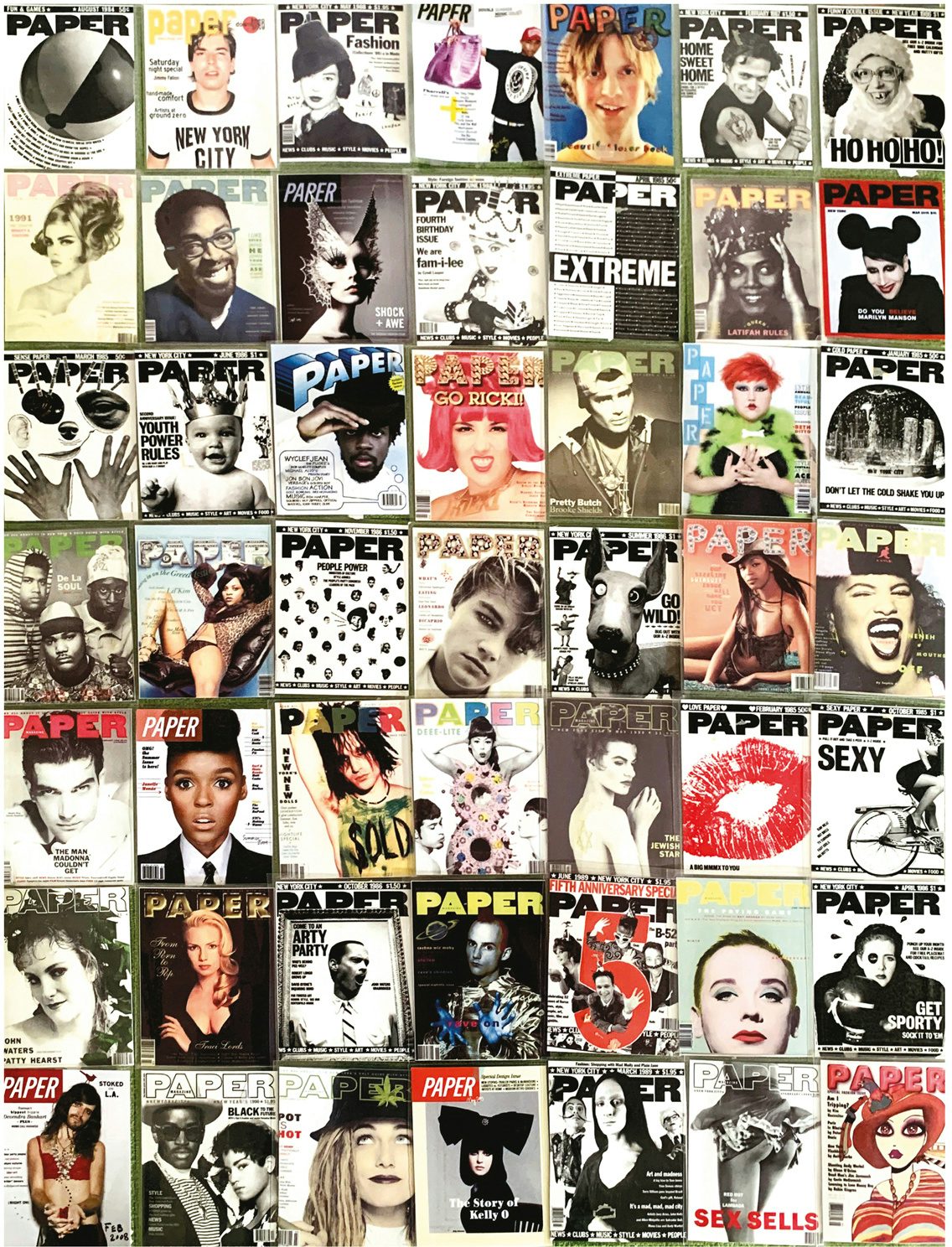

In creative terms, Hastreiter has worn many hats over the course of her five-decade career, whether as an artist, writer, editor, curator, or perhaps most notably as the co-founder of culture magazine Paper, which she launched with her friend David Hershkovits in 1984. She puts her multi-hyphenate approach down to the fact she’s “a fanatical collector and curator of stuff”. So much so, that she’s just released an entire tome dedicated to the subject.

Co-published by Damiani and Hastreiter’s own imprint Amazing Unlimited, Stuff explores New York’s cultural history through the lens of her expansive personal archive of art, fashion, design, photography, books and other ephemera. There’s also a focus on four “catastrophes”, including the AIDS epidemic and 9/11, along with 45 of her “amazing friends” from over the years, as she recounts tales such as an all-night party in the basement of an East Village church with Keith Haring, or an impromptu dinner at Trader Vic’s with Salvador Dalí and Joey Arias.

The seeds for Stuff were planted the week that the artist sold Paper in 2017, which also happened to be the same week that her mother passed away. While sorting through everything in her mum’s apartment, she also began looking back at the three decades’ worth of items she’d accumulated in her time at the helm of the magazine. “I had tonnes of stuff, I couldn’t even walk in my apartment. I got a studio in the same building downstairs and moved a lot of it, and it gave me something to do. I was like, I have amazing stuff,” she recalls.

Fast-forward to 2021 in the midst of the pandemic, and a milestone birthday for Hastreiter inspired her to finally do something with her personal archive. “When you turn 70, you kind of see the end,” she explains. “It’s like your last decade before you get dementia, or whatever’s going to happen. I don’t care about being old, but I saw the end. I realised I had so much in my brain to dump before I die, so I’ve got to get to work!”

At the same time, she was noticing a growing sense of nostalgia among younger generations for bygone eras that often played out before they were even born. “I love young people and I hang around with a lot of young people, but you see the kids start loving certain things, like the 80s. People are writing about the 80s and they get their information from Google or whatever. All these people are writing about what you lived through and they’re getting it wrong!”

Born and raised in New Jersey, Hastreiter studied at the California Institute of the Arts where she was mentored by the artist John Baldessari, before moving to New York City in 1976. When she first arrived, she wanted to be a full-time artist but didn’t have any luck with the male-dominated gallery world at the time. “They rejected me, so of course I was like, ‘I don’t want your art world’,” she says.

Instead, she started going out a lot, where she witnessed many of the city’s cultural happenings first hand. In downtown, the worlds of art, fashion and film were all merging as scenes such as punk were thriving, while in the Bronx hip hop was really beginning to take hold. “There became this collaboration and this conversation. The kids from the Bronx, all the early graffiti writers and breakdancers, they would come downtown and see the punk kids, and they were into it. There was this amazing exchange that was happening in those days, and it was all about culture.”

Paper was like a community, it was people collaborating and people sharing ideas. You can’t do that on social media, it’s very singular, it’s very siloed

Hastreiter’s first job was working as a shop girl in uptown Manhattan, where she sold clothes to the likes of Barbra Streisand and Jackie Kennedy. From there, she got a gig as the style editor at SoHo Week News, the newspaper founded by music publicist Michael Goldstein. When the paper went out of business a couple of years later, she and Hershkovits decided there was a gap for a magazine that would both celebrate and collaborate with New York’s radical creative class.

Paper came into the world as a Xerox-ed, DIY venture from the kitchen of Hastreiter’s Tribeca apartment. “We tried to raise money for two years and the same questions came up. ‘Is it a fashion magazine?’ Well, not really. ‘Is it a music magazine?’ Well, not really. No one would give us money because they didn’t understand it was going to be about culture. Eventually we met these two art directors and we all put in $1,000 and did it,” she says.

While the word digital wasn’t in anyone’s vocabulary when they started out, Paper was one of the early adopters of what became known as ‘desktop publishing’, becoming beta testers for Apple. “It was our dream to do a weekly, but we could only afford to do it monthly and David was like, ‘Well, if we do it online, we could do it weekly, we could even do it daily’,” she explains. They were also one of the first publishers to set up an in-house agency doing consultancy for brands. “It’s called influencer now, but they would come to us and say, ‘We want to do an ad campaign for this vodka, who should we put in the ad campaign?’”

After three decades at the helm of Paper, Hastreiter felt it was the right time to sell. “When the internet came along it became about numbers and about celebrities. I don’t like celebrities, I’m not a celebrity person. We would put people on the cover that no one had ever heard of who would become famous in ten years, but that wasn’t good for business,” she says. Despite this, one of the magazine’s most iconic moments under her stewardship came when she green-lit its 2014 cover of Kim Kardashian that saw its then CCO Drew Elliott coin the term ‘break the internet’.

“Drew invented that expression. Because the internet was just hot and Kim Kardashian had all these followers, so Drew said let’s make the whole issue about virality. Kim on the cover, and every article inside is going to be about people who have big followings. I said, ‘That’s a genius idea, let’s go.’”

While any cover featuring Kardashian would likely have made a splash at the time (particularly during the Kimye era), it was Hastreiter’s suggestion to have legendary photographer Jean-Paul Goude shoot the cover that took things to the next level. “He’d never heard of her because he’s French and he doesn’t go on the internet,” she laughs.

“Jean-Paul works very methodically, he doesn’t just shoot, he has a plan. So he gave us these four or five shots that he wanted to do, the first one being the champagne shot that he did first on Grace Jones,” she says. “And it turns out Kim was in between publicists, so she came by herself to the shoot with her hairdresser, or maybe her makeup person, and no cockblockers – no PRs.”

Having redone their site in preparation, when they released the pictures from the cover shoot they quickly racked up 13 million hits within a few hours. “Paper had a circulation of 75,000 for like 30 years, we never got above that. By the next morning everyone knew what Paper was. It was on every TV station, it was crazy. I remember Jeffrey Deitch, the art dealer, called me that morning and said, ‘This is art, Kim.’”

Since leaving the magazine, Hastreiter has continued to voraciously document cultural happenings in recent years. Currently, she is working on four books in addition to Stuff, writes a weekly Substack about the past, present and future of culture, and regularly publishes her series of ‘Memezeens’ that immortalise the radical viral art of the meme in print form (Bernie Sanders and his mittens are a personal highlight).

As part of what she calls the “straddle generation” (“I know how to use a typewriter and I know how to dial a phone, but I also know how to build a website”), she has a unique vantage point on the ongoing debate around whether the rise of digital is flattening culture. “Paper was like a community, it was people collaborating and people sharing ideas. You can’t do that on social media, it’s very singular, it’s very siloed. I think social media has isolated people and I think the ideas are less abundant because there’s not exchange.”

In today’s fragmented media landscape, the cultural influence of print magazines is a far cry from when Hastreiter first started Paper, but she does believe they still have an important role to play. “I say make them, do them. It’s about expressing people’s point of view. What’s a bad magazine is the Conde Nast types, where they don’t really have a vision. So you can’t say print is dead, I think corporations are dead.”

As for what the artist hopes people will take away from Stuff, she notes the importance of keeping history as truthful as possible. Towards the end of the book is an open letter from her titled “Dear kids”, which discusses how vital this will continue to be as we enter the age of AI. “If you don’t, when you get to be 70, someone’s going to be writing about Covid and Trump and they’re going to be writing about it all wrong. Everything’s perverted now and there’s no truth, the only truth is the witness of the person. So that’s how I ended the book, telling them you have to be responsible for your own history. This is just my history.”

Stuff: A New York Life of Cultural Chaos is published by Damiani and Amazing Unlimited; @kimpaper