The Monthly Interview: Rebecca Allen

As Tate Modern opens a new show on the advent of digital art, one of its early pioneers discusses the reasons it’s been overlooked historically and why she’s not interested in the new era of AI art

While you may or may not be familiar with her name, there are few living artists who’ve had as much influence on digital culture as Rebecca Allen. Starting out in the early 70s, she was one of the first people to use the computer as an artistic tool. Over the course of her five-decade career, she’s helped pioneer everything from motion-capture and 3D modelling to Artificial Life, as well as collaborating with cultural figures including Kraftwerk and Nam June Paik, aka the ‘father of video art’.

In recent years, the US artist has finally started to receive due recognition for her role in shaping the digital art landscape today. Her work is part of permanent collections including at MoMA in New York, and is increasingly being shown internationally, most recently as part of Tate Modern’s new blockbuster exhibition Electric Dreams. Featuring two of her most seminal pieces, Steps (1982) and Creation Myth (1985), the show places the artist’s body of work in the context of more than 70 other early innovators working before the dawn of the internet age.

Allen’s early interest in computers came while studying at Rhode Island School of Design, where she learned about how art movements such as Bauhaus, Constructivism and Futurism had been born out of the industrial age. “I thought, the computer age is going to have the next big impact on society,” she recalls. Going against her tutors, who like the rest of the art world then were of the view that “artists and computers don’t make sense”, she convinced the neighbouring Brown University to grant her access to its computer science lab, which was doing some of the earliest work with computer graphics at the time.

“I know it sounds pretty funny to say I wanted to create a new form of art but that’s where I was at that age, and I’ve really dedicated myself to that my entire career,” says Allen. “I knew looking at where computers might be going that it was such a limited group of people, primarily male computer scientists, that were inventing everything the machines could do. From the very beginning, I said this is way too important for society to let one narrow group of people define it.”

While most early examples of computer graphics tended to feature mathematical forms and geometric shapes, Allen was more interested in the technically challenging task of depicting human motion. One of the first artworks she created on the computer, Girl Lifts Skirt (1974), depicted a woman lifting her skirt up on a repeating cycle. “I liked that positioning of something slightly erotic, feminine, sexual being done on a computer, which was always called a cold, heartless thing,” she says. “That was really talking to the times, how women were perceived, the objectification of them, and trying to get above that,” she says.

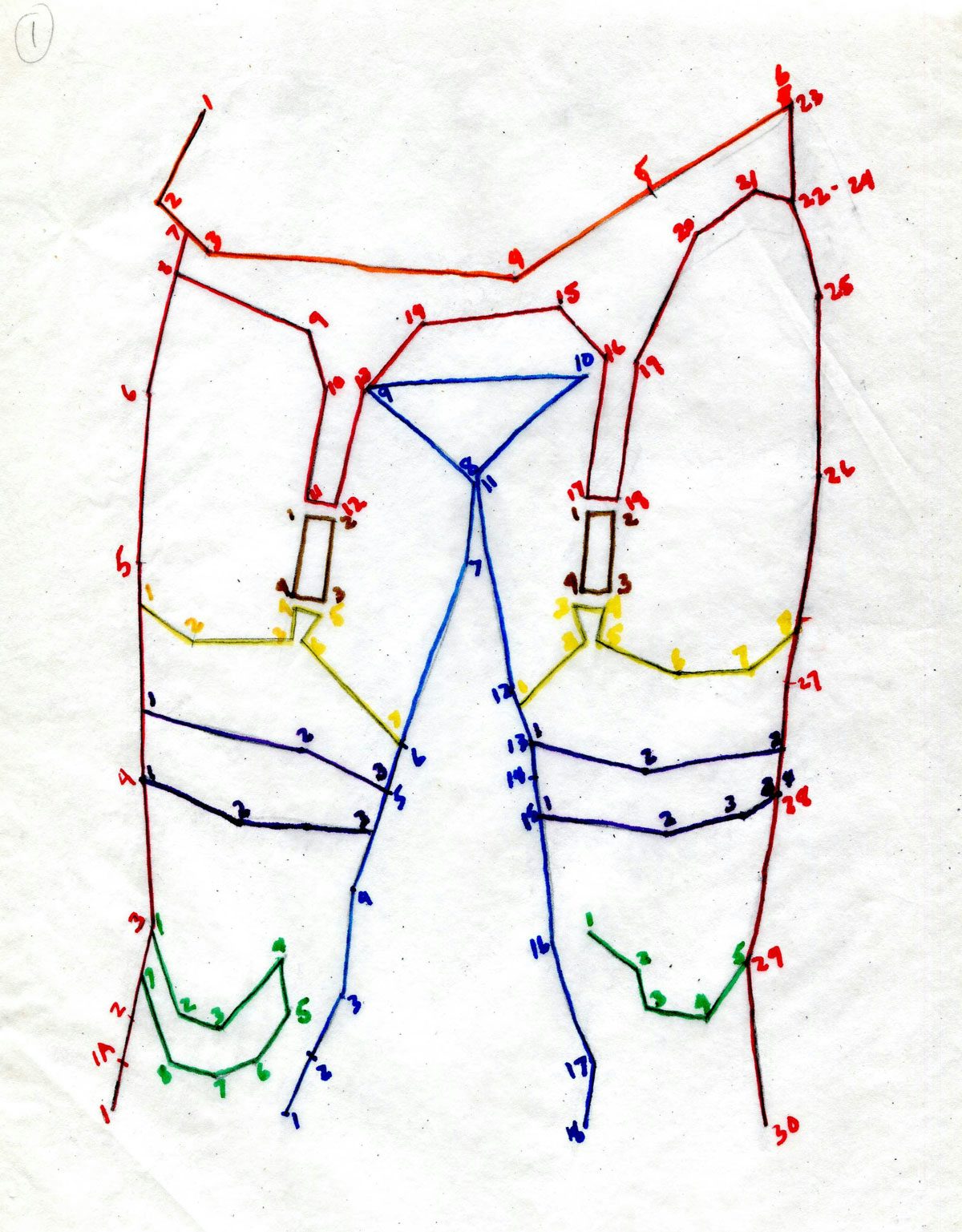

Creating hand-drawn animations at that point was an incredibly labour-intensive process, requiring Allen to create individual drawings for every fraction of a second. But the bigger challenge the artist faced was how to infiltrate the world of computer art as a young woman. “It was really dawning on me how restrictive life was for women and their careers, and in the art world itself,” she recalls. “But since there were already challenges being a woman and an artist, the idea of working in a very male tech environment didn’t faze me too much, because that’s the way the world worked at that point.”

In 1980, Allen joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Architecture Machine Group (now known as MIT Media Lab), which was focused at the time on the burgeoning practice of 3D animation. “There was no commercial software of any kind, so to do anything you had to either do it yourself and program everything, or with bigger systems you were working with a team of computer scientists,” she explains. “This was the lab that was inventing a lot of the software we use today – paint systems, 3D modelling, 3D animation, rendering, textures – all of the things that everyone blissfully uses today.”

It’s less to me about what’s going to be the next cool tool to use, it’s where can artists help society take us into the future?

Of the handful of 3D models in existence at that time, two of them were invented by people who came to work at MIT. One of those was Ed Catmull, who had already made the first 3D model of a female body and later went on to co-found entertainment giant Pixar. Alongside her work as a researcher at the lab, Allen created a number of artworks using the 3D model, including Swimmer (1981) and Steps (1982), the latter of which marked her first collaboration with the Joffrey Ballet company.

Given her fascination with human motion, dance was a rich source of inspiration for the artist from the outset. In 1982, she worked with choreographer Twyla Tharp on The Catherine Wheel, a feature-length dance film with music by David Byrne, which sees a computer-generated character play the role of St Catherine. Broadcast on the BBC and across Europe on PBS, it marked her first steps from the hidden world of computer science labs into mainstream culture.

“I could see that I would never be able to show this work so I had to think about, how can I get it out there?” she explains. “[The Catherine Wheel] was actually the first time the public had seen a 3D computer model moving on TV, but of course nobody knew what computer graphics meant.”

With the birth of the MTV era in the early 80s, Allen also recognised its broader potential as a means to distribute experimental avant-garde animation to millions of people. “Music videos in those days, there weren’t teams of executives telling you what to do. They took what they got at that point, so that gave me a huge amount of freedom, which was great. I was also very impacted by art movements that were dealing with pop culture, and felt the computer really aligned with that because I could see it was going to affect everything in our culture,” she says.

The artist created two music videos for Lynn Goldsmith under her Will Powers stage name, Adventures in Success (1983) and Smile (1983). These attracted the attention of Kraftwerk, who were fast emerging as one of the pioneers of electronic music, and the artist ended up creating the award-winning music video for their 1986 track Musique Non Stop. In the same vein, her Creation Myth piece for New York superclub the Palladium, which also features in the new Tate Modern show, lived alongside commissioned pieces by art world titans including Keith Haring and Basquiat.

While the Tate Modern exhibition acknowledges the impact of Allen’s work in the context of the pre-internet era, her output has been just as prolific in recent years. As computers were speeding up in the early 90s, she joined video game company Virgin Games to help develop the thinking around 3D games for newly released platforms such as Nintendo 64 and PlayStation. And in the 2010s, recognising that virtual reality was now advanced enough for the art world to explore, she created a series of VR artworks including Inside (2016), The Tangle of Mind and Matter (2017) and Life Without Matter (2018).

One of her latest pieces, Biophilia (2024), was designed on a computer but, in a first for the artist, is printed on canvas. Depicting her own face mapped onto a generic female body which is embracing a brain, it’s a commentary on our shifting relationship with the natural world. “Biophilia is defined as an innate quality of humans to love nature. This is why when we go out into nature to hike or something, you can feel it affecting you,” she says. “But I look now and I’m thinking, maybe we don’t really have a love of nature. If we do, why are we destroying it all?”

Having worked with early forms of AI back in the 80s, it’s not surprising that Allen isn’t really interested in the new era of AI art, or the creative industries’ obsession with new technology in general. “I’ve always been way ahead in a sense that didn’t help me that much,” she explains. “It took a long time for anyone to catch up, or even understand what I was doing, and now I see that technology has raced ahead of the ideas with things like AI, where nobody can reflect and explore what we’re really doing. It’s less to me about what’s going to be the next cool tool to use, it’s where can artists help society take us into the future? Because we’re moving at a non-human pace now.”

One thing that Allen is happy about, however, is the greater appreciation of where digital art came from in the first place, especially given that it now occupies a near omnipresent place in our visual culture. “There was a feeling for so long in the art world that they hate computers, but I see that changing now,” she says. “Being able to critique it and think about it in an artistic way, then you can start to see how one thing really did impact the other and this is just a continuum. It’s being positioned now where I always wanted it to be – an extension of humanity. As we hurtle into the future, what’s important to humanity and what are artists doing about it?”

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet is at Tate Modern in London until June 1; rebeccaallen.com