How games are changing our understanding of war

A new exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum explores the relationship between video games and violence, uncovering how game designers are offering new perspectives on the history of conflict

“I think there’s a clear tension between war being entertaining, and the reality of warfare,” says Chris Cooper, co-curator of a new exhibition delving into the ways game designers are tackling our fascination with conflict. Hosted at London’s Imperial War Museum (IWM), the exhibition – entitled War Games: Real Conflicts | Virtual Worlds | Extreme Entertainment – places footage from games, and interactive pieces, alongside real-life artefacts, in a show that leans into the friction between war as entertainment, and the moral grey area that produces.

It’s not the first time the museum has examined the relationship, having hosted Reel to Reel: A Century of War Movies back in 2016. Cooper explains that the concept for War Games was born from this show, which similarly explored “the impact movies had on the public’s perception of war and conflict, and how much impact that had on people’s understanding of war”. Video games, as “the next big interpretive media to be emerging in the entertainment sphere” felt like a natural next step.

Visitors to the show are first given a chance to get their bearings, with war games situated, as Cooper explains, in “a broader cultural consumption of war as a form of entertainment”. Gameplay appears alongside images from comic books, clips of war movies such as 1917, and footage from TV shows such as Blackadder Goes Forth, which is set during the First World War. Taken together it’s a reminder of our long-time fascination with the subject – which is emphasised by the addition of a chess set and game of Battleship from IWM’s collection. “Play is an integral form of our relationship with conflict and war stories,” notes Cooper. “Chess is obviously an ancient war game – the set [on display] was carved by a prisoner of war.”

So why are designers, directors, and storytellers so fascinated by the subject? “We’ve always played at war, and conflict is at the heart of any good storytelling,” Cooper tells CR. “Why is it that war provides such a good setting for stories? It’s the fact it offers such a broad range of experience, you’ve got the classical good versus evil stories. If you think about the way the Second World War is portrayed in movies, and also video games, it’s quite a Boys’ Own adventure approach to a lot of stories. It’s quite heroic in a lot of ways, and quite action packed.

“But it’s also very human at a basic level, so you can explore such a range of emotions and experiences – whether that’s the heartbreaking act of war, the devastation it causes, or some of those, perhaps, more romantic ideas of war. I think war provides a setting to cover any sort of story related to the human experience, and it provides the most extreme examples of some of those emotions that are involved in those stories too. And you can see that across medias, and across storytelling.”

It might be a rich source of narrative impetus, but that doesn’t remove the uncomfortable truth that studios can make millions by repackaging historic conflicts as bloody entertainment. As Cooper says, and as the show emphasises, many of these titles immerse players in hyper realistic environments, using high definition graphics and sound design to recreate the experience as closely as possible.

The exhibition even includes a real-life sniper rifle which developer Rebellion – a sponsor of the show – photographed and recreated for its Sniper Elite series of games. Visitors are encouraged to squirm, with a pair of cosmetic prosthetics placed next to the gun as a reminder of the damage weapons inflict in the real world. “We wanted to counterpoint and highlight that tension between the real-life impact on somebody who would have suffered the same sorts of injuries, and what that would have meant in terms of their recovery and longer term psychological impact – to emphasise the tensions between the virtual and the real,” says Cooper.

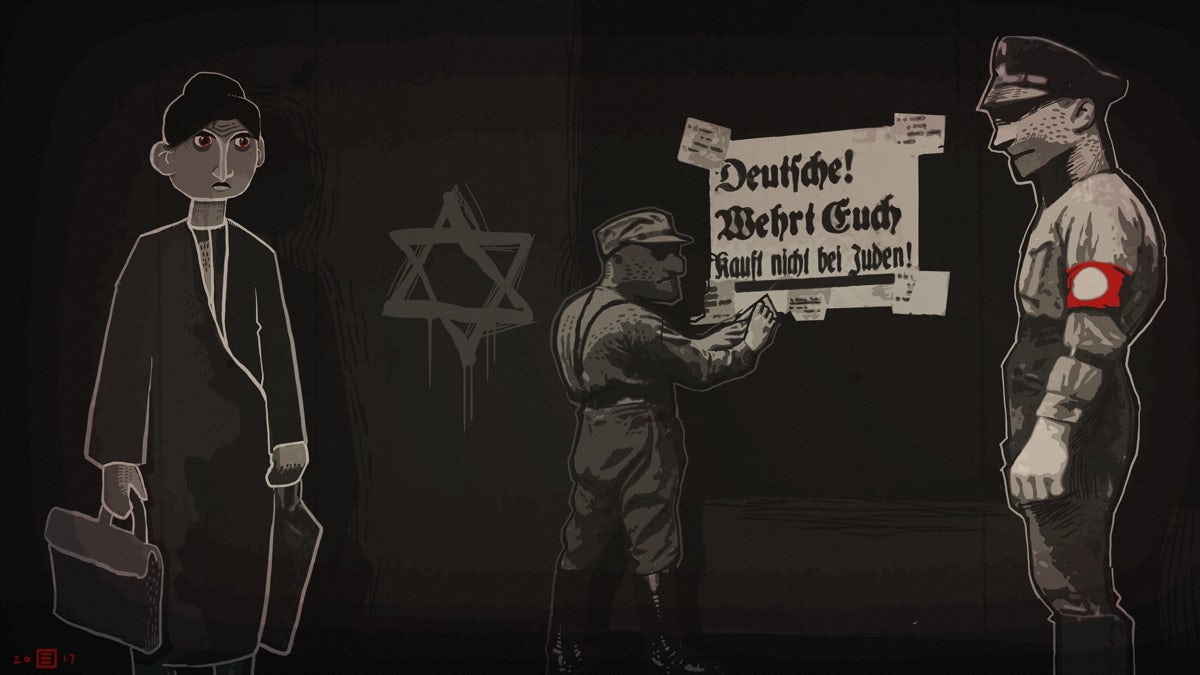

The exhibition leaves viewers to come to their own conclusions about the ethics of video game violence based on historic events – “It’s a grey area,” says Cooper – however it does emphasise that game designers are offering increasingly nuanced interpretations of conflict. The curator says the museum wanted to question whether games could “affect some sort of truth or reality, whether they could recreate an aspect of conflict or warfare that enabled you to experience it in some sort of true way”.

Several games featured in the show support this idea that new creative approaches are emerging – for example, the as-yet-unreleased Six Days in Fallujah developed by Highwire Games. The game places players in the middle of the 2004 Second Battle of Fallujah in Iraq, and attempts to recreate the fear and uncertainty experienced by American soldiers navigating an unpredictable urban environment. The designers based the game on interviews with US marines, as well as film and photographs from the event, designing a system that procedurally generates Fallujah each time the game is played, so the experience is always different.

“Everything looks and feels real … but what they were interested in doing was recreating that feeling of not knowing what’s round every corner,” explains Cooper. “They interviewed Iraqi civilians and other participants in the battle to try to get the broadest sense, and the gameplay is interspersed with a documentary element – you’ll hear an interview and you’ll be put into a similar position.”

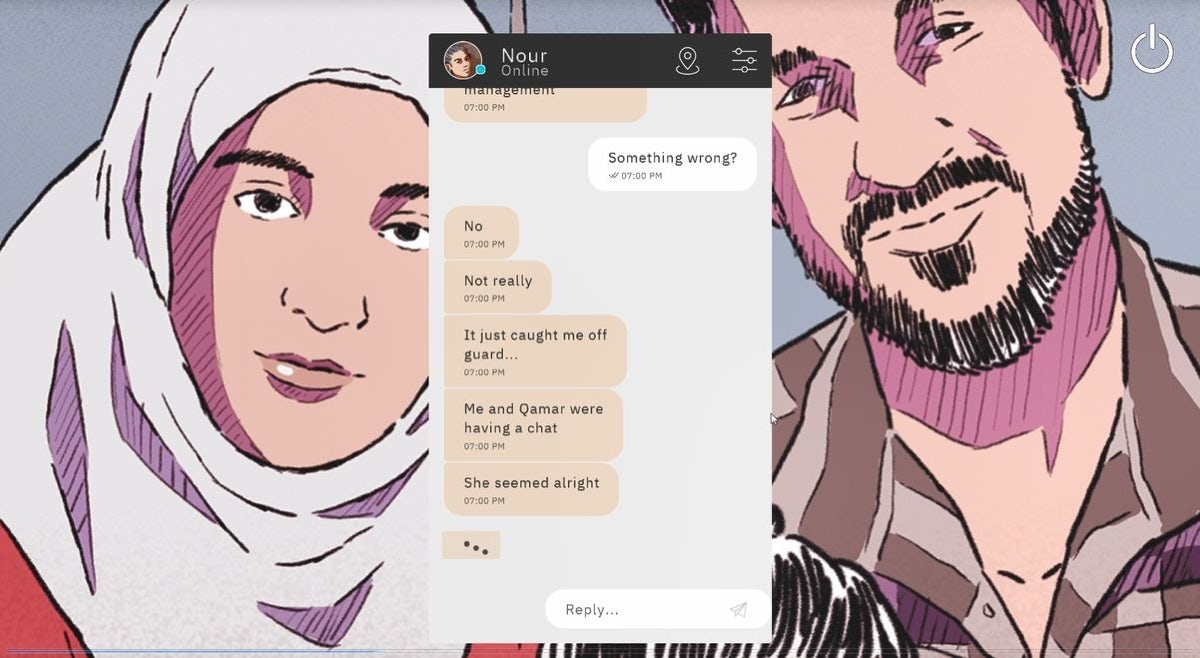

Bury Me My Love, developed by the Pixel Hunt, Arte France and Figs, also speaks to the ways studios are creating empathy. The text-based game puts the player in the shoes of the husband of a Syrian refugee, making the journey to Europe and, according to Cooper, is heavily based on research into real-life experiences.

And 11-11 Memories Retold, co-developed by DigixArt and Aardman Animations, depicts events of the First World War in a striking, painterly style that’s quite different from the hyper-realism of hugely popular war games such as Call of Duty. The show’s curators have placed this game next to paintbrushes belonging to British painter John Nash, who was an official war artist, to encourage visitors to reflect on how works of art and creativity influence our perceptions of these events.

While huge money-makers such as Call of Duty aren’t going to disappear any time soon, Cooper believes there’s a new generation of games designers with a heightened awareness of the state of conflict around the globe and looking to create different narratives. Developers are also plumbing less familiar war narratives – for example, Battlefield V includes a storyline around a Norwegian resistance fighter. As Cooper says, many players might have never have encountered these narratives or perspectives.

The flip side to that is undoubtedly more sinister, as the final part of IWM’s exhibition makes clear. Video games controllers are a design success story, with the typical two- or three-pronged design becoming almost ubiquitous. Most players can pick up a control and understand how to use it – which is perhaps why the US military used an Xbox controller to operate cameras on drones in Iraq. The show features one of these very controllers, used on a Desert Hawk UAV, placed next to a tank simulator handle that looks disturbingly familiar.

War Games: Real Conflicts | Virtual Worlds | Extreme Entertainment is on display at London’s Imperial War Museum until May 28; iwm.org.uk