A look at the challenges facing creative education

Creative computing artist and educator Jazmin Morris discusses why she decided to leave full-time academia and how educational institutions can better prepare the next generation of talent

Jazmin Morris has always had an outsider’s perspective on the creative industries – from choosing to study fine art at Chelsea College of Arts through to entering the tech space via her work as a creative computing artist. “Being a Black woman that was raised in poverty was extremely challenging,” she says. “The privilege involved in a fine arts degree – I wasn’t aware of it and just did it anyway. I think that’s why I’ve carved my own path, but I didn’t want to carve my own path – it just really didn’t exist.”

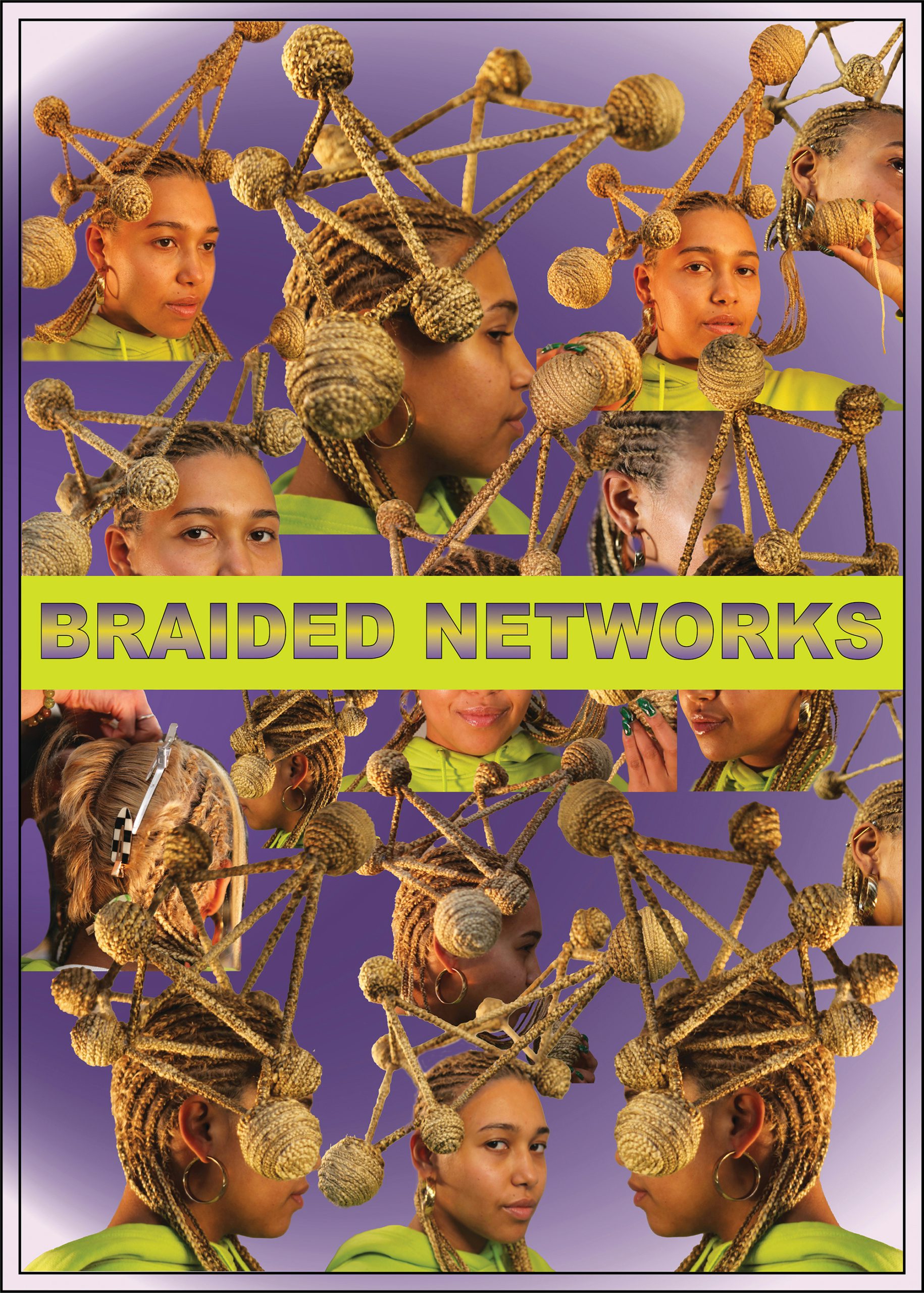

Since graduating in 2018, Morris has tried her hand at everything from creative and tech consultancy through to university lecturing. In her personal practice, she explores representation and inclusivity in technology through self-initiated projects such as Braided Networks, which saw her use hair braiding as a medium to criticise the hierarchy behind AI development. But she’s arguably best known as the founder of Tech Yard, a free creative computing club providing introductory workshops to a broad range of creative technologies, which she launched as part of her work with UAL’s Creative Computing Institute.

Motivated by her own experience of the education and tech worlds, where she was often the only Black woman in the room, Morris had already been running workshops with local organisations, schools and charities when UAL first approached her in 2020. “I figured the more people I could inspire to use creative computing to make things, slowly the more diverse the scene would get,” she says. The university subsequently created an official teaching role for her and gave her the funding to formalise Tech Yard as part of the CCI’s wider work. “They gave me full reins, but I then named it, created a bit of a brand for it and ran everything under that name.”

From the outset, the driving force behind Tech Yard was that it was designed for anyone and everyone, whether they had an existing interest in tech or not. “I always knew I wanted to reach people who wouldn’t typically get access to this technology and ethos,” Morris says. “But at the same time, being a marginalised person myself, I’ve never been interested in putting people in a box and ignoring intersectionality. I never wanted it to just be for people of colour, or for queer people, or for kids on school dinners – I find that stuff exclusionary. So I never formally said what the audience was on purpose.”

As she became more deeply involved in UAL’s work, Morris says she also found herself feeling increasingly invested in how higher education can better explore the technologies shaping our world today. Established in 2018, the CCI’s unique blend of creativity and tech, through courses such as Creative Robotics and Data Science and AI, is exactly what she needed when she was starting out.

I figured the more people I could inspire to use creative computing to make things, slowly the more diverse the scene would get

“If I graduated from my foundation now, I know for a fact I’d be applying to that institution, but it didn’t exist. I didn’t always feel like the tutors fully understood digital art, and many of my peers [weren’t even] interested in this area, so I found myself jumping across years and courses to find people.”

While she found her work as an educator fulfilling, balancing Tech Yard alongside the workload of lecturing at both the CCI and Central Saint Martins became increasingly challenging for Morris to keep up with. She eventually hit breaking point earlier this year, deciding to leave full-time academia and move up to Leeds in order to spend more time on her personal practice. “I was just getting more and more burned out, and then I started to see the flaws in my position at the university,” she explains.

“I think the penny dropped when I was asked to do my PGCert for the third time after dropping out twice. I knew it was important, and I needed it to progress my teaching career, but that’s a whole degree. You’re told you’re going to have time taken out of your teaching to do it, but when the hours add up it doesn’t actually happen, especially because of the positions I held across the university. I realised that I’d turned into an academic and that I didn’t have the privilege to be successful in academia without losing myself.”

While undoubtedly the right decision for her personally, Morris recalls agonising over quitting for months. “It hurt a lot at the time because I knew the difference I was making. And that’s not to blow my own trumpet, content is content, and there are a lot of amazing teachers, but it was specifically that I was teaching art and technology as a working-class Black woman. I know I was making a difference, and I saw the students that saw themselves in me.”

There’s been much debate around the state of creative education in recent years, particularly when it comes to the gap between what the industry expects from new talent and what institutions can provide them. While Morris acknowledges that universities are aware of this changing landscape, she says the major challenge is just how rapidly everything is moving. “It is a can of worms because, do we need to restructure education entirely? I think we’re going to have to find a new hybrid, collaborative way of educating that isn’t entirely dependent on academics and technicians and credits – and the industry needs to be more involved as well.”

Asked whether she believes people should reconsider traditional arts degrees altogether, she says: “It’s definitely not ‘don’t go to uni’, but understand why you’re going, what you want out of it, where you want your career to start, and make sure you’re on the right course and surrounded by the right peers.”

As for what the future holds for Morris, she’s currently exploring her personal practice again, prioritising meaningful outreach work with disadvantaged groups, such as asylum seekers, and doing occasional teaching at UAL. She’s also not ruling out a return to academia altogether – as long as it’s on her own terms.

“I have been interested in creating my own institution or course. There are quite a few alternative techie institutions that exist which are inspiring,” she says. “I think we’ll see how my career goes, because if I’m meant to be an artist then I guess that’ll happen, and if I still feel there’s something missing then I might re-explore education and what it means to me. Definitely never say never.”