Rachel Gogel on the rise of fractional leadership

The independent design executive discusses what she’s learned about building creative teams, the increasing prevalence of fractional creative leadership, and why it signals a broader shift away from traditional ways of working

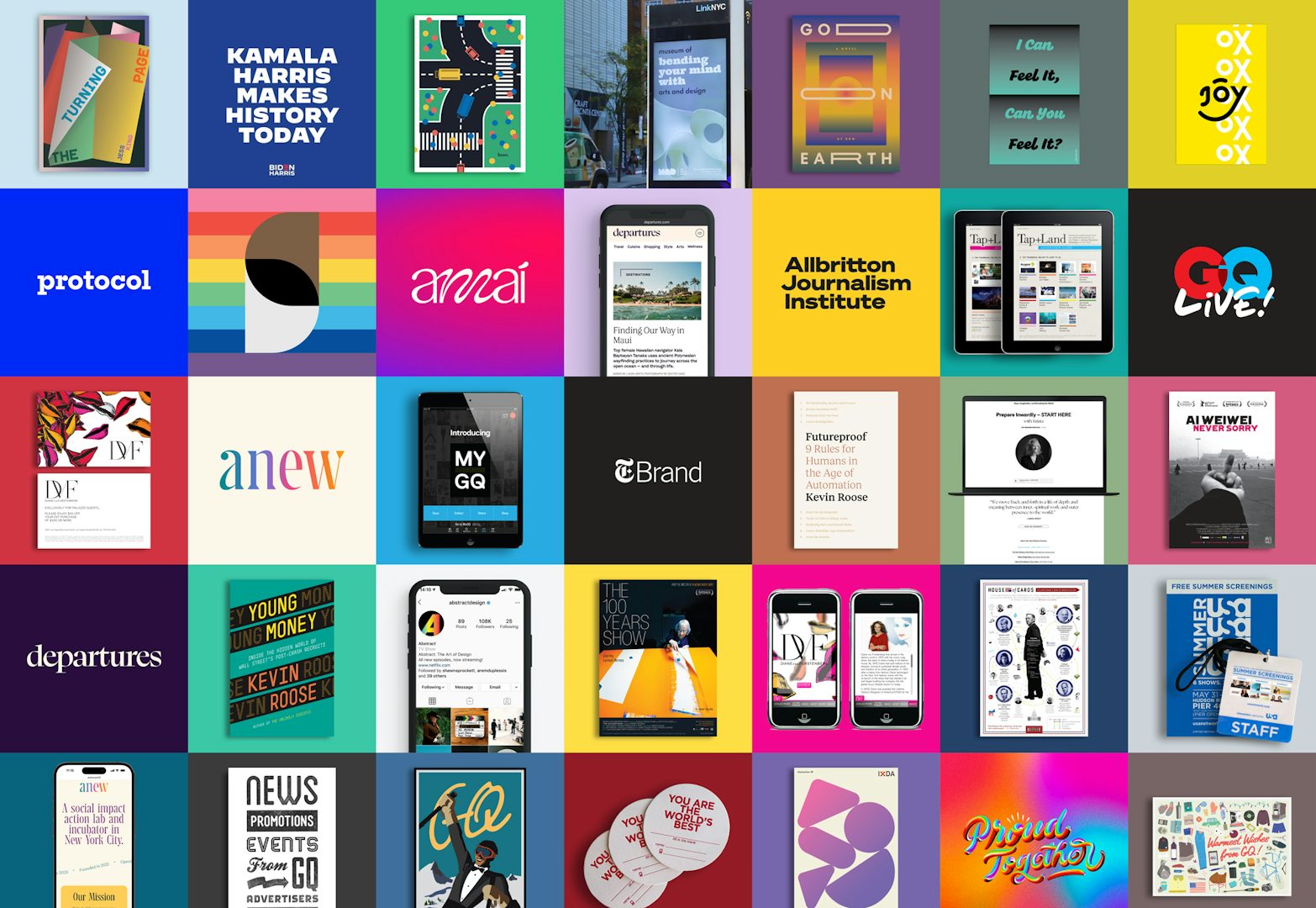

Rachel Gogel has spent the last 16 years building creative teams from the ground up. She took on her first associate art director role aged just 23 at GQ, where she headed up a team of creatives who were all older than her as the publication sought to expand its digital offering. A couple of years later, she was brought on to establish the creative team for the New York Times’ first-ever branded content division, T Brand Studio. And as head of creative for the Facebook app, she curated an in-house team of over 30 people responsible for unifying the brand’s in-product visual systems.

“In all of those dynamics, I would break down the walls between teams or organisations that historically had been there – ask questions, understand what they did, and what their priorities were,” says Gogel. “There was a lot of empathy building and speaking their language, and then finding ways to involve them in the process. So even though I wasn’t doing this consciously, I’ve always been interested in organisational design and culture.”

Today, the San Francisco-based creative director runs her own consultancy informed by her experiences both in-house and agency side. But since going independent during the pandemic, she’s increasingly realised that her happy place is playing the role of a fractional design leader. If you’re new to that term, it isn’t defined as your typical freelancer or consultant. Instead, it’s a flexible model where businesses engage seasoned professionals to come in at a very high level for a fraction of the time, whether it’s a couple of days a week or on a per project basis. Already fairly common practice in the executive and marketing worlds, the model is becoming increasingly recognised within the creative industries too.

In Gogel’s case, fractional leadership looks like everything from helping companies through transitional periods, building out their creative teams, and even training her full-time replacements. Specific projects that she’s worked on to date include influencing the development of creative agency Giant Spoon’s publishing arm, which resulted in American Express’ digital lifestyle magazine Departures; developing Airbnb’s first-ever internal brand playbook; reshaping employee experiences and culture programmes for Dropbox’s in-house design team; leading a brand identity project for Warner Bros; and taking on a fractional head of creative gig for her former employer Godfrey Dadich Partners.

Working in this way allows her to scratch the itch of what she loved about leading teams in the earlier part of her career. “I have these opportunities where I can be embedded in an organisation, have a team of people that basically have a dotted line to me, I can show up for people, I can mentor, I can coach, I can influence big bodies of work, and then I’m off. I don’t get caught in the internal politics, I’m not in back-to-back meetings like if you were a manager,” she explains.

It’s not one size fits all, particularly when it comes to giving feedback, or communicating in a certain way to someone, or building certain processes or cultures

While the role itself is different from full-time, the same principles of creating a team culture that helps breed creative success still very much apply. “It’s not one size fits all, particularly when it comes to giving feedback, or communicating in a certain way to someone, or building certain processes or cultures. You can’t just think, that worked for that place so I’m going to do the exact same thing over here. Pretty early on, I realised every individual has different needs. I have to show up for them,” she adds.

Despite the success Gogel’s found with this new mode of working, she’s noticed that fractional roles are still the hardest to come by. “None of the gigs that I’ve gotten so far had been listed as a job,” she says. “They’re all something that over time I convinced an agency to invest in. One of my pitches was, ‘you get five days of my brain in a two-day window’. The biggest hesitation from companies is onboarding and really understanding the culture. Are you someone’s manager or not if you’re sitting outside of the company? And do you really understand the brand?”

While it’s clearly not right for every circumstance, the key benefit for brands and agencies considering going down the fractional route is that it offers a highly flexible and lower-commitment solution without the potential risks associated with a permanent hire, which is inevitably a more time-consuming and expensive process. And for creatives, Gogel believes that the rise of fractional offers an opportunity for experienced self-employed professionals to carve out a space for themselves at a time when perspectives of the freelancer model are shifting.

“If you use the term ‘freelance’ people ask, is this your full-time job? Are you a junior? Are you more of a support?,” she explains. “I don’t know if it’s always been that way or if it’s over time, but most of the people I talk to just don’t use that term anymore, which is why you’re starting to see more people say, ‘I’m an independent creative director’. I think there’s something about even just owning the idea of ‘I’m on my own’.”

She also notes that while, for a long time, the pinnacle of success in the ad and design industries was rising through the ranks of an agency with a view to eventually setting up on your own, technological advances and post-pandemic hybrid working models have made solopreneurship much more accessible, particularly for women and those from marginalised groups. Couple that with the reality of widescale layoffs, shrinking budgets and larger agency structures fracturing, and it’s no surprise that experienced creative leaders are becoming disillusioned with the traditional measures of success.

“When I was starting out, if you had a two-year gig on your resume [people] would question, why are you hopping around? Whereas now it’s almost weird if you stay longer than two years,” says Gogel. “I think there’s just less loyalty to companies, because companies are still figuring how to show up for their employees and make them feel like they care about them. I think there’s a lot of creativity happening around what a career can look like, finding that Venn diagram of what brings you the most joy and figuring out, can that sustain my livelihood?”